The Tunnel of Death

July 2018

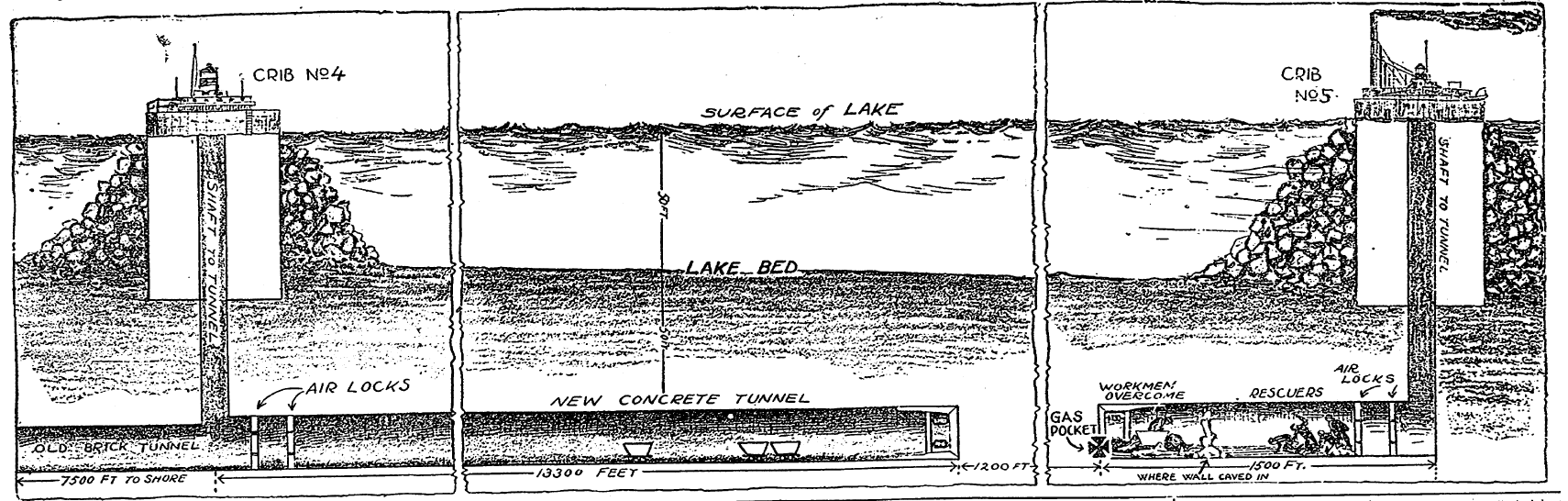

Looking due north, over the lake, from Cleveland, Ohio, an orange object is clearly visible in the distance. To someone not familiar with Cleveland, the object may be mistaken for a ship approaching the port of Cleveland. The object, however, is not a ship; it is a water intake, known as Crib No. 3, which is connected by a five-mile tunnel to a shore-based pumping station. About a mile west of Crib No. 3 is a white buoy, which is not visible to the naked eye from the shoreline. This buoy marks the location of another (albeit submerged) water intake, Crib No.5, where a patently brave rescue occurred more than a 100 years ago. Read on to learn more; its a Patently Interesting® story!

Crib No. 3 and its associated tunnel were built between 1896 and 1904 to deliver clean water to the city of Cleveland. The cost of Crib No. 3 was frightful in terms of human life. More than 39 men were killed building the tunnel as a result of a number of mishaps, including a series of natural gas explosions. Another 31 died from complications arising from the “bends”, bringing the total number of deaths up to 70. However, the single worst accident in the history of Cleveland water was still yet to come.

Soon after the construction of Crib No. 3 and its tunnel were completed, plans were made to build Crib No. 5 as a replacement for Crib No. 4, which was located a short distance west of the mouth of the Cuyahoga River and a mile from shore. Contrary to the connotation of its name, Crib No. 4 was older than Crib No. 3, having been completed in 1890.

Construction of Crib No. 5 began in January of 1912 and was completed seven months later. Built from more than one million feet of 12-inch timbers, Crib No. 5 was a massive octagonal structure, having a width of about 100 feet and a height of more than 63 feet. On August 2, 1912, two tugs towed the crib five miles out into Lake Erie, where it was sunk in fifty-two feet of water and weighted down with several thousand tons of stone. Thereafter, a temporary superstructure, including a house for workmen was built on top of the crib.

Although Crib No. 5 was completed and installed by the end of 1912, work on its tunnel did not begin until March of 1914. Work was delayed mainly because of the City’s failure to receive budget-compliant bids for the tunnel work. However, the White Hurricane of November 1913 also delayed the start because of the damage it did to Crib No. 5 (as well as Crib Nos. 3 and 4). Work on the tunnel began after the city decided to perform the work itself, instead of subcontracting it out.

Crib No. 3 and its associated tunnel were built between 1896 and 1904 to deliver clean water to the city of Cleveland. The cost of Crib No. 3 was frightful in terms of human life. More than 39 men were killed building the tunnel as a result of a number of mishaps, including a series of natural gas explosions. Another 31 died from complications arising from the “bends”, bringing the total number of deaths up to 70. However, the single worst accident in the history of Cleveland water was still yet to come.

Soon after the construction of Crib No. 3 and its tunnel were completed, plans were made to build Crib No. 5 as a replacement for Crib No. 4, which was located a short distance west of the mouth of the Cuyahoga River and a mile from shore. Contrary to the connotation of its name, Crib No. 4 was older than Crib No. 3, having been completed in 1890.

Construction of Crib No. 5 began in January of 1912 and was completed seven months later. Built from more than one million feet of 12-inch timbers, Crib No. 5 was a massive octagonal structure, having a width of about 100 feet and a height of more than 63 feet. On August 2, 1912, two tugs towed the crib five miles out into Lake Erie, where it was sunk in fifty-two feet of water and weighted down with several thousand tons of stone. Thereafter, a temporary superstructure, including a house for workmen was built on top of the crib.

Although Crib No. 5 was completed and installed by the end of 1912, work on its tunnel did not begin until March of 1914. Work was delayed mainly because of the City’s failure to receive budget-compliant bids for the tunnel work. However, the White Hurricane of November 1913 also delayed the start because of the damage it did to Crib No. 5 (as well as Crib Nos. 3 and 4). Work on the tunnel began after the city decided to perform the work itself, instead of subcontracting it out.

Construction of Tunnel for Crib No. 5

Construction of Tunnel for Crib No. 5

The tunnel for Crib No. 5 was constructed in two sections: one section extending outward from Crib No. 4 and one section extending inward from Crib No. 5, with the two sections meeting under the lake about midway between Crib No. 4 and Crib No. 5. Each of the tunnel sections was bored through the clay lakebed using a moving “shield”, which was a steel cylinder, having a 12 foot diameter and a 15 foot length. The shield had a front cutting edge and a rear tailpiece, with an erector disposed in-between. The erector was operable to place six interlocking concrete blocks into a ring configuration in the tailpiece. The rings formed formed by the erector as the shield moved forward formed a concrete liner for the tunnel. A series of hydraulic jacks disposed just inward from the cutting edge and braced against the rings moved the shield forward through the clay. As the shield moved forward, workers (referred to as “sand hogs”) used a large semi-circular cutter to lop off large chunks of clay, which were cut up and loaded into muck cars that were moved by a hydraulic locomotive to an elevator located in a shaft extending upward to the crib. After being carried up to the crib by the elevator, a muck car would be moved out to the end of a cantilevered runway, where its load of clay would be emptied into the lake. In the foregoing manner, each tunnel section advanced through the lakebed at a rate of 27 feet every twenty-four hours.

An important feature of the tunneling operation was the use of compressed air to keep water out of the tunnel sections and to stabilize the surrounding clay. Each tunnel section had an air lock disposed toward the elevator shaft. The air lock comprised a pair of spaced-apart doors that provided an air-tight seal between the tunnel and the elevator shaft. Air was pumped into each tunnel section to raise its pressure to around 20 psig, which is equivalent to a water depth of about 46 feet. When the tunnel for Crib No. 3 was built, compressed air of between 30 and 40 psig was used, which resulted in numerous cases of the bends, as well as uncomfortable working conditions for the sand hogs.

Because of the carnage that occurred during the construction of Crib No. 3 and its tunnel, the safety and welfare of the sand hogs were major concerns for the city in building the tunnel for Crib No. 5. It was these concerns that persuaded the city to reduce the tunnel pressure to 20 psig to reduce the number of cases of the bends. It also resulted in the strict enforcement of new safety rules, which, inter alia, prohibited smoking or the handling of lamps, due to the possible presence of gas in the tunnel sections. Despite these precautions, important and seemingly obvious safety measures were still missing. For example, there was no telephone, telegraph or radio communication facilities between Crib No. 5 and the shore. In addition, there was no rescue equipment, such as breathing devices or pulmotors (resuscitation devices) stored at Crib No. 5.

On the night of July 24, 1916, disaster struck. At 9:22 p.m., a massive gas explosion rocked the tunnel section being built from Crib No. 5. The explosion blew out concrete liner blocks, mangled rail lines and filled the end of the tunnel section with debris, burying 11 sand hogs who had been working there. With the tunnel pressure gauge swinging wildly, workers on the crib immediately knew what happened and informed John Johnston, the supervisor of Crib No. 5. Johnston quickly organized a rescue party consisting of himself and six other volunteers. They made their way into the tunnel through the air lock, but did not get very far. Not more than 100 yards from the air lock, Johnson collapsed from the gas. Fellow rescuer, Peter McKenna and lock-tender, William Dolan, dragged Johnston back to the elevator, which transported them up to the crib. Johnston and McKenna would be the only survivors of the first rescue party.

During Johnston’s ill-fated rescue attempt, the men on the crib launched rocket flares and sounded the crib’s steam whistle to alert people on shore that help was needed. Eventually, help arrived around midnight in the form of Gus Van Duzen, the project superintendent, and a party of 12 volunteers. Unfortunately, they did not bring any rescue equipment with them, and they rushed head-long into the same deadly predicament the first rescue party had found themselves in. One by one the second rescue party were felled by the gas in the tunnel. Three or four members of the second rescue party made it back up top. After that, the men on the crib heard nothing from the men below. There was just silence, an incredibly awkward silence, which went on for several hours.

An important feature of the tunneling operation was the use of compressed air to keep water out of the tunnel sections and to stabilize the surrounding clay. Each tunnel section had an air lock disposed toward the elevator shaft. The air lock comprised a pair of spaced-apart doors that provided an air-tight seal between the tunnel and the elevator shaft. Air was pumped into each tunnel section to raise its pressure to around 20 psig, which is equivalent to a water depth of about 46 feet. When the tunnel for Crib No. 3 was built, compressed air of between 30 and 40 psig was used, which resulted in numerous cases of the bends, as well as uncomfortable working conditions for the sand hogs.

Because of the carnage that occurred during the construction of Crib No. 3 and its tunnel, the safety and welfare of the sand hogs were major concerns for the city in building the tunnel for Crib No. 5. It was these concerns that persuaded the city to reduce the tunnel pressure to 20 psig to reduce the number of cases of the bends. It also resulted in the strict enforcement of new safety rules, which, inter alia, prohibited smoking or the handling of lamps, due to the possible presence of gas in the tunnel sections. Despite these precautions, important and seemingly obvious safety measures were still missing. For example, there was no telephone, telegraph or radio communication facilities between Crib No. 5 and the shore. In addition, there was no rescue equipment, such as breathing devices or pulmotors (resuscitation devices) stored at Crib No. 5.

On the night of July 24, 1916, disaster struck. At 9:22 p.m., a massive gas explosion rocked the tunnel section being built from Crib No. 5. The explosion blew out concrete liner blocks, mangled rail lines and filled the end of the tunnel section with debris, burying 11 sand hogs who had been working there. With the tunnel pressure gauge swinging wildly, workers on the crib immediately knew what happened and informed John Johnston, the supervisor of Crib No. 5. Johnston quickly organized a rescue party consisting of himself and six other volunteers. They made their way into the tunnel through the air lock, but did not get very far. Not more than 100 yards from the air lock, Johnson collapsed from the gas. Fellow rescuer, Peter McKenna and lock-tender, William Dolan, dragged Johnston back to the elevator, which transported them up to the crib. Johnston and McKenna would be the only survivors of the first rescue party.

During Johnston’s ill-fated rescue attempt, the men on the crib launched rocket flares and sounded the crib’s steam whistle to alert people on shore that help was needed. Eventually, help arrived around midnight in the form of Gus Van Duzen, the project superintendent, and a party of 12 volunteers. Unfortunately, they did not bring any rescue equipment with them, and they rushed head-long into the same deadly predicament the first rescue party had found themselves in. One by one the second rescue party were felled by the gas in the tunnel. Three or four members of the second rescue party made it back up top. After that, the men on the crib heard nothing from the men below. There was just silence, an incredibly awkward silence, which went on for several hours.

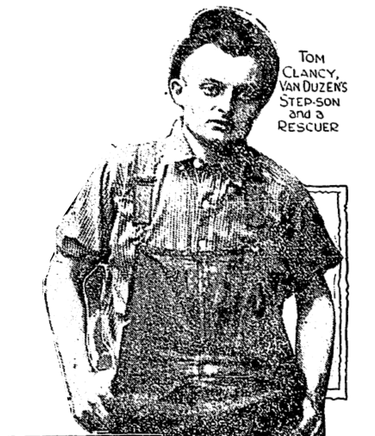

Finally, the silence was broken around 2:30 AM when Thomas Clancy and his friend, James Keating arrived at the crib on a tugboat they had commandeered. Clancy was the 23 year old step-son of Van Duzen and had come to the crib at the request of his mother, who had heard about Van Duzen’s plight. Clancy and Keating wrapped wet towels around their heads and then descended the shaft in the elevator, together with a tunnel worker by the name of James McGrath. Making their way to the air lock, they looked through the bullseye (viewing port) and saw three men lying motionless inside. They broke the bullseye to vent the bad air in the air lock and then opened the outer door and retrieved the men inside, placing them on a car and wheeling them to the elevator, which transported them up to the crib. The three men that Clancy, Keating and McGrath had rescued were Harry Hatcher, John McCormick and Patrick Sullivan. Unfortunately, Hatcher and McCormick died as they were being transported to shore on a tugboat, probably due to the absence of pulmotors at the crib.

Upon their return to the crib, Clancy and Keating conferred with Cleveland Water Commissioner, Charles Jaeger, and Utilities Director, Thomas Farrell, about releasing the pressure in the tunnel section to vent the gas. It was not an easy decision because doing so would risk collapsing the tunnel. Believing that the benefits outweighed the risks, Commissioner Jaeger decided that the pressure should be released. Clancy and Keating once again wrapped wet towels around their heads and descended the shaft to the air lock, where they tried to open the valves to release the pressure, but were prevented from doing so by the gas, which forced them to retreat back to the crib.

In the meantime, a tug had arrived from Cleveland, carrying two smoke helmets and a pulmotor. (N1) It was now almost 5:00 AM in the morning. Keating and a policeman, Richard Kistemaker, donned the smoke helmets and went back to the air lock with Clancy, who went unprotected. Once again, they were turned back by the gas. This time, however, Clancy was felled by the gas and was brought back unconscious. While Clancy was being resuscitated with the pulmotor, Keating and Kistemaker returned to the air lock and successfully opened the valves to reduce the pressure in the tunnel section. A little while later, at around 7:15 AM, a rapping was heard on an air pipe, indicating that someone was alive in the tunnel section. Keating and Kistemaker went down again and retrieved Patrick Kehoe and Martin Nelson from the second rescue party, who had managed to make their way to the inner door of the air lock. However, Keating and Kistemaker did not venture into the tunnel itself. (N2)

Upon their return to the crib, Clancy and Keating conferred with Cleveland Water Commissioner, Charles Jaeger, and Utilities Director, Thomas Farrell, about releasing the pressure in the tunnel section to vent the gas. It was not an easy decision because doing so would risk collapsing the tunnel. Believing that the benefits outweighed the risks, Commissioner Jaeger decided that the pressure should be released. Clancy and Keating once again wrapped wet towels around their heads and descended the shaft to the air lock, where they tried to open the valves to release the pressure, but were prevented from doing so by the gas, which forced them to retreat back to the crib.

In the meantime, a tug had arrived from Cleveland, carrying two smoke helmets and a pulmotor. (N1) It was now almost 5:00 AM in the morning. Keating and a policeman, Richard Kistemaker, donned the smoke helmets and went back to the air lock with Clancy, who went unprotected. Once again, they were turned back by the gas. This time, however, Clancy was felled by the gas and was brought back unconscious. While Clancy was being resuscitated with the pulmotor, Keating and Kistemaker returned to the air lock and successfully opened the valves to reduce the pressure in the tunnel section. A little while later, at around 7:15 AM, a rapping was heard on an air pipe, indicating that someone was alive in the tunnel section. Keating and Kistemaker went down again and retrieved Patrick Kehoe and Martin Nelson from the second rescue party, who had managed to make their way to the inner door of the air lock. However, Keating and Kistemaker did not venture into the tunnel itself. (N2)

Garrett A. Morgan

Garrett A. Morgan

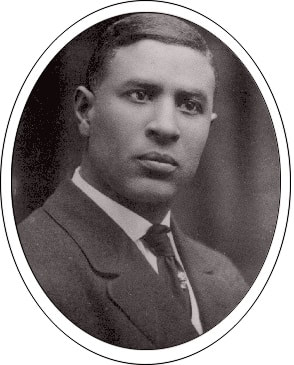

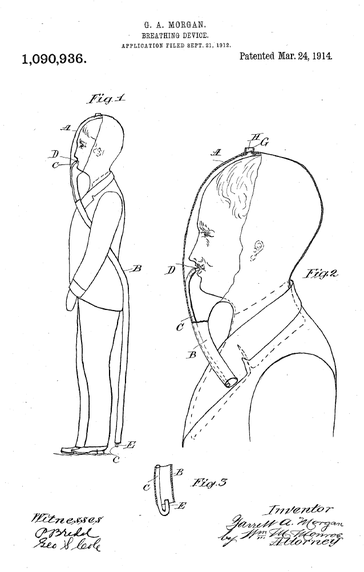

Not long after Clancy and Keating had made their first rescue, John Chafin, a Cleveland policeman at the crib recalled a demonstration of a smoke hood he had witnessed several years before. Chafin persuaded authorities that they needed to get in touch with the man who had given the demonstration and who happened to live locally. That man was Garrett A. Morgan, a successful African-American inventor and businessman. Morgan had received two patents (U.S. Patent Nos. 1090936 and 1113675) for a safety hood that was sold by The National Safety Device Company, of which Morgan was an owner. The safety hood was commercially successful, winning a number of awards and being utilized by fire departments throughout the nation. The safety hood consisted of a hood that enclosed a wearer’s head and was connected to a bifurcated breathing tube. In an earlier, first model, the ends of the the breathing tube extended to the floor and operated on the principal that fresher air (free from smoke and lighter, toxic gases) was located toward the floor of a burning building. In a later, second model, the ends of the breathing tube were connected to an air bag connected to a wearer’s waist. The second model was better suited for situations where heavier toxic gases were present. Both the first and second models were simple to put on and did not involve complicated hoses, valves or oxygen tanks. (N3)

Morgan Patent for Smoke Hood

Morgan Patent for Smoke Hood

Beginning at 3:00 AM, Morgan received three phone calls in quick succession from Chafin, a marine officer and the city detective office, requesting his help at Crib No. 5. Without even bothering to put shoes on, Morgan gathered his brother Frank, a neighbor and a number of his safety hoods, and headed down to the pier, where a fire tug, the George W. Wallace, was waiting to take them to the crib. As soon as Morgan arrived at the crib, he asked for volunteers to accompany him into the tunnel. Only his brother Frank, Thomas Castelberry and the indefatigable Clancy volunteered for the mission. They all donned Morgan’s safety hood, which is believed to have been the second model, and loaded themselves onto the elevator. As the rescue party was about to descend into the shaft, Cleveland Mayor Harry Davis shook Morgan’s hand and said “goodbye”, clearly displaying uncertainty as to whether Morgan and the others would return.

Disembarking from the elevator, Morgan led the rescue party toward the tunnel, still barefoot and without any light source. Blindly slopping his way through the muck, Morgan made his way through the air lock and into the tunnel itself. He soon came upon the grotesquely distorted body of Clarence Welch, clutching a “bug” (flashlight). Taking the flashlight from the dead body of Welch, Morgan proceeded further into the tunnel, until he heard a faint groaning sound coming from a second body lying in the mud. The second body was Van Duzen, covered in mud and barely alive. Morgan and the other members of the rescue party loaded Van Duzen and Welch onto a car and wheeled them to the elevator, which brought them to the surface.

Disembarking from the elevator, Morgan led the rescue party toward the tunnel, still barefoot and without any light source. Blindly slopping his way through the muck, Morgan made his way through the air lock and into the tunnel itself. He soon came upon the grotesquely distorted body of Clarence Welch, clutching a “bug” (flashlight). Taking the flashlight from the dead body of Welch, Morgan proceeded further into the tunnel, until he heard a faint groaning sound coming from a second body lying in the mud. The second body was Van Duzen, covered in mud and barely alive. Morgan and the other members of the rescue party loaded Van Duzen and Welch onto a car and wheeled them to the elevator, which brought them to the surface.

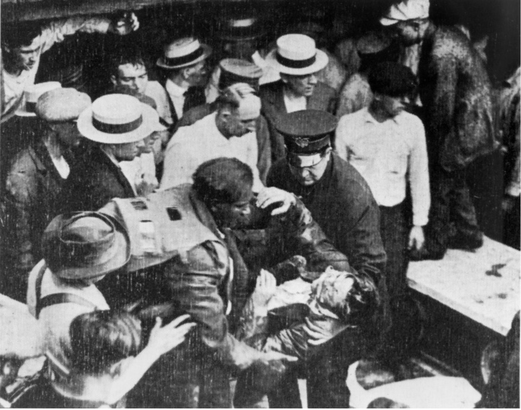

Morgan with One of the Men he Rescued

Morgan with One of the Men he Rescued

While Clancy remained with Van Duzen, Morgan and the rest of his rescue party returned to the tunnel to look for more survivors. On their second trip into the tunnel, they rescued one more survivor (most likely Henry McNamara) and retrieved three dead bodies. Morgan would make at least one more trip into the tunnel, but no more survivors were found. As it turned out, McNamara would be the last man rescued from the tunnel.

The tunnel explosion had claimed the lives of twenty-one men; eleven in the original explosion and ten who attempted to rescue them. A perfunctory investigation was hastily conducted less than three days later, even though the bodies of some of the dead sandhogs were still trapped in the tunnel. Notwithstanding the paucity of safety equipment at the crib and the fact that a significant level of gas was known to exist in the tunnel on the morning of the explosion, nobody was found accountable for the horrific loss of life. Everyone was exonerated. Mayor Davis succinctly summed up his position, stating: “I believe every man did what he thought was best.” Echoing Davis, Utilities Director Farrell elaborated: “Some men displayed more courage than others and some used better judgment than others. But I am convinced every man did what he thought was right at the time.”

Some of the courageous men Farrell was referring to were awarded medals by the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission. These men were Thomas Clancy, James Keating, James McGrath and William Dolan. Unfortunately, other men who also displayed uncommon bravery were not similarly recognized. These men included Peter McKenna, Richard Kistemaker, Thomas Castelberry, and Garrett and Frank Morgan. Why their bravery was not recognized is not entirely clear; it may have been due to cronyism, racism and/or a mistaken belief that they did not risk their lives because they used safety equipment. Regardless of the reason, they undoubtedly displayed bravery. When the Morgan brothers, Castelberry and Clancy entered the tunnel, with Garrett Morgan leading the way, gas was still present and there was a heightened risk of tunnel collapse (because the pressure had been reduced). In addition, there was a risk of electrocution from downed electrical lines that were still live and sparking in the wet tunnel. Even with safety equipment, conditions were far from safe.

Although it was late in coming, Garrett Morgan posthumously received recognition for the heroism he displayed under Lake Erie way back in July of 1916. In a fitting tribute to Garrett, the Cleveland Water Department, in 1991, named the pumping station that pumps water from Crib No. 5 to Cleveland and its suburbs the Garrett A. Morgan Water Treatment Plant.

Notes:

(N1) - The smoke helmets were most likely oxygen helmets manufactured by the Draeger Oxygen Apparatus Co., the American subsidiary of the German company, Drägerwerk Heinr. und Bernh. Dräger, now known as Drägerwerk AG (hereinafter “Drägerwerk”).

Drägerwerk also invented and manufactured the pulmotor. The Drägerwerk smoke helmets were fed oxygen from connected oxygen tanks and were not designed for use in conditions exceeding normal atmospheric pressure.

(N2) - Clancy (and presumably Keating) believed the (Drägerwerk) smoke helmets were not to be used in conditions exceeding normal atmospheric pressure. Most likely, it was for this reason that the rescuers with the smoke helmets did not enter the tunnel itself.

(N3) - Unlike the Drägerwerk smoke helmets, Morgan’s safety hood had no pressure limitations and would permit Morgan and his rescue team to be the first to enter the tunnel itself.

The tunnel explosion had claimed the lives of twenty-one men; eleven in the original explosion and ten who attempted to rescue them. A perfunctory investigation was hastily conducted less than three days later, even though the bodies of some of the dead sandhogs were still trapped in the tunnel. Notwithstanding the paucity of safety equipment at the crib and the fact that a significant level of gas was known to exist in the tunnel on the morning of the explosion, nobody was found accountable for the horrific loss of life. Everyone was exonerated. Mayor Davis succinctly summed up his position, stating: “I believe every man did what he thought was best.” Echoing Davis, Utilities Director Farrell elaborated: “Some men displayed more courage than others and some used better judgment than others. But I am convinced every man did what he thought was right at the time.”

Some of the courageous men Farrell was referring to were awarded medals by the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission. These men were Thomas Clancy, James Keating, James McGrath and William Dolan. Unfortunately, other men who also displayed uncommon bravery were not similarly recognized. These men included Peter McKenna, Richard Kistemaker, Thomas Castelberry, and Garrett and Frank Morgan. Why their bravery was not recognized is not entirely clear; it may have been due to cronyism, racism and/or a mistaken belief that they did not risk their lives because they used safety equipment. Regardless of the reason, they undoubtedly displayed bravery. When the Morgan brothers, Castelberry and Clancy entered the tunnel, with Garrett Morgan leading the way, gas was still present and there was a heightened risk of tunnel collapse (because the pressure had been reduced). In addition, there was a risk of electrocution from downed electrical lines that were still live and sparking in the wet tunnel. Even with safety equipment, conditions were far from safe.

Although it was late in coming, Garrett Morgan posthumously received recognition for the heroism he displayed under Lake Erie way back in July of 1916. In a fitting tribute to Garrett, the Cleveland Water Department, in 1991, named the pumping station that pumps water from Crib No. 5 to Cleveland and its suburbs the Garrett A. Morgan Water Treatment Plant.

Notes:

(N1) - The smoke helmets were most likely oxygen helmets manufactured by the Draeger Oxygen Apparatus Co., the American subsidiary of the German company, Drägerwerk Heinr. und Bernh. Dräger, now known as Drägerwerk AG (hereinafter “Drägerwerk”).

Drägerwerk also invented and manufactured the pulmotor. The Drägerwerk smoke helmets were fed oxygen from connected oxygen tanks and were not designed for use in conditions exceeding normal atmospheric pressure.

(N2) - Clancy (and presumably Keating) believed the (Drägerwerk) smoke helmets were not to be used in conditions exceeding normal atmospheric pressure. Most likely, it was for this reason that the rescuers with the smoke helmets did not enter the tunnel itself.

(N3) - Unlike the Drägerwerk smoke helmets, Morgan’s safety hood had no pressure limitations and would permit Morgan and his rescue team to be the first to enter the tunnel itself.

Proudly powered by Weebly