The First Patent Examiners

August 2018

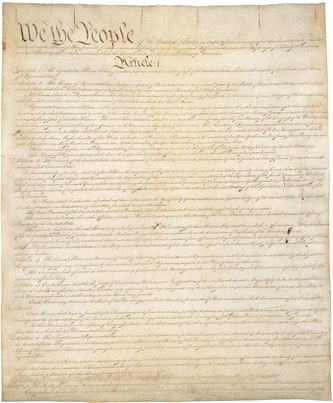

The U.S. Constitution

The U.S. Constitution

The foundation of the U.S. patent system was established on March 4, 1789 when the Constitution of the United States came into force. The Constitution provided that: "The Congress shall have the power....to promote the progress of Science and useful Arts by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries". This provision of the Constitution became effective on April 10, 1790, when George Washington signed into law the first patent act of the United States, which was entitled "An Act to Promote the Progress of the Useful Arts."

The Patent Act of 1790 provided for the creation of a three-man board that was empowered to grant patents for inventions or discoveries that were deemed “sufficiently useful and important”.The board was comprised of the Secretary of State, the Secretary of War and the Attorney General. At the time, the Secretary of State was Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of War was Henry Knox and the Attorney General was Edmund Randolph. Thus, not only were these three distinguished gentlemen part of George Washington’s Cabinet, they were the nation’s first patent examiners!

The Patent Act of 1790 provided for the creation of a three-man board that was empowered to grant patents for inventions or discoveries that were deemed “sufficiently useful and important”.The board was comprised of the Secretary of State, the Secretary of War and the Attorney General. At the time, the Secretary of State was Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of War was Henry Knox and the Attorney General was Edmund Randolph. Thus, not only were these three distinguished gentlemen part of George Washington’s Cabinet, they were the nation’s first patent examiners!

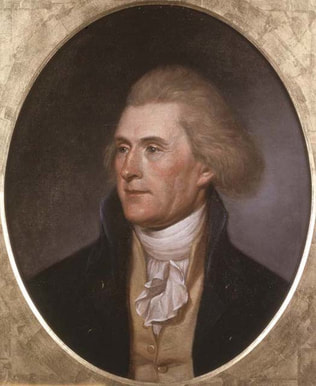

Thomas Jefferson - 1791

Thomas Jefferson - 1791

Pursuant to the 1790 Patent Act, the Secretary of State was responsible for the administration of the patent system. Since Jefferson is well known as being an inventor and a man of unlimited scientific curiosity, it seems only natural that Jefferson would have been the first patent adminstrator. What is less well known, however, is that Jefferson was very suspicious of any type of monopoly and had, less than two years before the 1790 Patent Act, expressed his belief that all monopolies should be prohibited, even limited monopolies, such as those to authors and inventors through copyright and patent. While he subsequently softened his position, Jefferson never really felt comfortable with patents. So, it is actually quite ironic that Jefferson was made the first patent administrator.

In addition to essentially being the first patent commissioner, Jefferson was also the de facto first Librarian of Congress. Even though Washington had recommended to Congress that patents and copyrights be treated together, Congress decided to have two separate acts for patents and copyrights. While the Copyright Act of 1790 was to be administered by the federal district courts, a copy of each map, chart or book that was copyrighted had to be provided to the Secretary of State. As such, Jefferson's office served as a repository of American publications like the later Library of Congress. It's no wonder then that Jefferson, as president, later signed a bill in 1802 that allowed the president to appoint a Librarian of Congress and to establish a Joint Committee on the Library to regulate and oversee it.

In addition to essentially being the first patent commissioner, Jefferson was also the de facto first Librarian of Congress. Even though Washington had recommended to Congress that patents and copyrights be treated together, Congress decided to have two separate acts for patents and copyrights. While the Copyright Act of 1790 was to be administered by the federal district courts, a copy of each map, chart or book that was copyrighted had to be provided to the Secretary of State. As such, Jefferson's office served as a repository of American publications like the later Library of Congress. It's no wonder then that Jefferson, as president, later signed a bill in 1802 that allowed the president to appoint a Librarian of Congress and to establish a Joint Committee on the Library to regulate and oversee it.

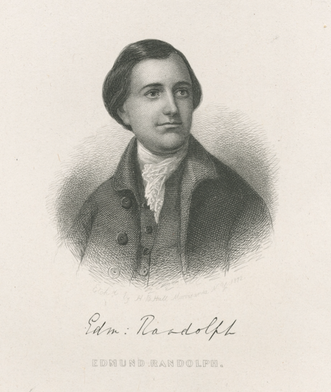

Edmund Randolph

Edmund Randolph

Although Jefferson was the administrator of the fledgling patent system and did most of the work, the Patent Act required that two of the three members of the board, which Jefferson referred to as the "Board of Arts", had to agree on the issuance of a patent. Accordingly, all of the members would read each patent application that was submitted to the Secretary of State and would then discuss its merits with the other members. The Board of Arts met on the last Saturday of every month to discuss submitted applications. Initially, the Board members would read the applications together and discuss them on the same day, but this became unworkable, so the members later read them on their own before their monthly meeting. The Attorney General (Edmund Randolph) would read an application first to make sure it met all of the formal requirements. He would then forward the application to Jefferson, who would review it thoroughly and then forward it to Knox.

Most of the substantive review of patent applications was done by Jefferson. He would review each patent application to determine whether the invention was workable and constituted more than an obvious improvement on a known device. At times, Jefferson would even invite inventors to his office to demonstrate their inventions.

As each member of the Board reviewed a patent application, they would write their examination opinion and any proposed amendment on the document. Once all of the members of the Board completed their review of an application, the chief clerk of the State Department, Henry Remsen, Jr., would go through the notes on the application and determine if there was a general consensus on the examination and any proposed amendments. If so, Remsen would prepare a summary of the agreed-to points and present it to the Board at their next meeting. If, however, there was a material disagreement among the members, the disagreement would be discussed among the members at the meeting.

Most of the substantive review of patent applications was done by Jefferson. He would review each patent application to determine whether the invention was workable and constituted more than an obvious improvement on a known device. At times, Jefferson would even invite inventors to his office to demonstrate their inventions.

As each member of the Board reviewed a patent application, they would write their examination opinion and any proposed amendment on the document. Once all of the members of the Board completed their review of an application, the chief clerk of the State Department, Henry Remsen, Jr., would go through the notes on the application and determine if there was a general consensus on the examination and any proposed amendments. If so, Remsen would prepare a summary of the agreed-to points and present it to the Board at their next meeting. If, however, there was a material disagreement among the members, the disagreement would be discussed among the members at the meeting.

General Henry Knox

General Henry Knox

Jefferson, Knox and Randolph took their review of patent applications very seriously. Reportedly, their review was so critical and rigid that they rejected most of the patent applications that were received by Jefferson. For the unlucky inventors whose applications were rejected, there was no redress. The Board had absolute authority and its decisions were not appealable. Because of the Board's stringent review and absolute authority, only three patents were granted during the first year of the Patent Act (1790), and only forty-four more were granted in the next two years (1791, 1792). Needless to say, this dearth of granted patents and other grievances led to the early demise of the 1790 Patent Act, which was replaced with the Patent Act of 1793.

The 1793 Patent Act eliminated the examination of patent applications, making the grant of patents an essentially automatic and clerical procedure. While this sped up the issuance of patents, it introduced a whole host of new problems that festered until 1836 when examination of patent applications was re-instituted.

The 1793 Patent Act eliminated the examination of patent applications, making the grant of patents an essentially automatic and clerical procedure. While this sped up the issuance of patents, it introduced a whole host of new problems that festered until 1836 when examination of patent applications was re-instituted.

Proudly powered by Weebly