Dr. John Gorrie

Dr. John Gorrie

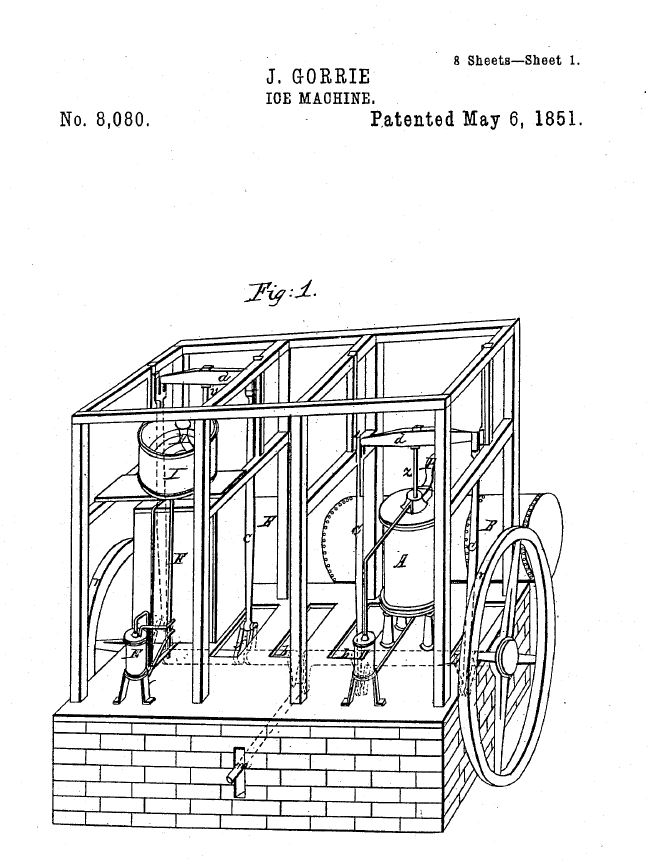

On May 6 of the year 1851, U.S. Patent No. 8,080 issued to John Gorrie for an "Ice Machine". It was the first U.S. patent for the mechanical manufacture of ice. The '080 patent incorrectly gives New Orleans as the residence of Gorrie, who instead lived in Apalachicola, Florida. At the time, Apalichicola was the second largest seaport on the Gulf coast and was a major outlet for cotton grown in Georgia, Alabama and the Florida panhandle. During the summer, it was not uncommon for the Apalachicola hospital to be filled with visiting sailors and local dock workers who were suffering from malaria or yellow fever. And it was a desire to help the suffering of these people that led to Gorrie's invention.

Gorrie was a doctor by profession. After graduating from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Western District of New York, Gorrie worked as a physician in Abbeville, South Carolina, where he became interested in treating malaria. This interest led him to accept a commission as medical officer in charge of the U.S. Marine Hospital at Apalachicola. After moving to the port town in 1833, Gorrie quickly became integrated into the local community. Within a year he was made postmaster and two years after that he became president of the Pensacola Bank. A year later, he was elected mayor of Apalachicola. All the while, Gorrie maintained his interest in treating in malaria.

mosquito

mosquito

Gorrie subcribed to the then-prevalent miasmatic theory of disease, which was that "bad air" caused diseases, such as malaria and yellow fever. Indeed, the term "malaria" itself originates from medieval Italian: "mala aria", which translates to "bad air". Gorrie believed that the rotting organic matter from the swamps surrounding Apalachicola were the cause of the malaria plaguing the town. As such, he recommended draining the swamps and constructing only brick buildings in the town. If not for his firm belief in the miasmatic theory, Gorrie may have discovered that the mosquito was the source of malaria decades before Ronald Ross established the connection. As it was, Gorrie came very close, noting that "Gauze curtains, though chiefly used to prevent annoyance and suffering from mosquitos, are thought also to be sifters of the atmosphere and interceptors and decompsers of malaria."

Gorrie also incorrectly believed that malaria could be cured if a patient's temperature was artificially lowered. Toward that end, Gorrie began to experiment with cooling the evirons of his patients by, first by blowing air over suspended tubs of ice and then, later, through mechanical means. With regard to the latter, Gorrie devised a crude vapor-compression refrigeration system in which air was first compressed by a steam engine and then was allowed to expand, thereby causing cooling. Gorrie had been using this system for several years to cool his patients when one day the system stopped working because it had iced up. Realizing the importance of what had happened, Gorrie decided to change his focus from air conditioning to ice making. He also decided to give up the practice of medicine to pursue the manufacture of ice.

Gorrie also incorrectly believed that malaria could be cured if a patient's temperature was artificially lowered. Toward that end, Gorrie began to experiment with cooling the evirons of his patients by, first by blowing air over suspended tubs of ice and then, later, through mechanical means. With regard to the latter, Gorrie devised a crude vapor-compression refrigeration system in which air was first compressed by a steam engine and then was allowed to expand, thereby causing cooling. Gorrie had been using this system for several years to cool his patients when one day the system stopped working because it had iced up. Realizing the importance of what had happened, Gorrie decided to change his focus from air conditioning to ice making. He also decided to give up the practice of medicine to pursue the manufacture of ice.

Gorrie's Ice Machine

Gorrie's Ice Machine

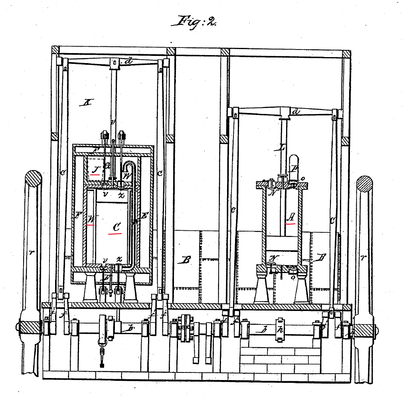

Gorrie modified his apparatus to make ice by, inter alia, using water to cool the air as it was being compressed and using salt water to help drop the temperature of the expanding air below the freezing point of water. The air was compressed in a first pump (A) driven by a steam engine or other motive source, while the air was expanded in a second pump (C), with the action of the second pump (C) being used to help with the operation of the first pump (A). A jacket (W) filled with salt water surrounded the second pump (C) and a container (J) holding the water to be frozen was disposed next to the jacket (W). It was this machine that was the subject of Gorrie's '080 patent.

Gorrie had a prototype of his ice-making machine built in Cincinnati and shipped down the Mississippi river to New Orleans, where it was reassembled, with much difficulty. The prototype was not well constructed and only worked intermittently. These difficulties with the prototype were compounded by bad publicity Gorrie received from Northern newspapers, which Gorrie attributed to Frederic Tudor, the "Ice King", who controlled the Northern ice trade. Despite these setbacks, Gorrie was able to obtain support from a New York businessman, who funded the construction of a large-scale version of Gorrie's ice making machine. However, just as the machine was being completed, the New York businessman died and the machine was sold at auction. This was the end of Gorrie's quest to commercialize his ice machine. Dispirited and financially ruined, Gorrie himself died soon thereafter, on June 29, 1855. He was only 51 years old.

Gorrie had a prototype of his ice-making machine built in Cincinnati and shipped down the Mississippi river to New Orleans, where it was reassembled, with much difficulty. The prototype was not well constructed and only worked intermittently. These difficulties with the prototype were compounded by bad publicity Gorrie received from Northern newspapers, which Gorrie attributed to Frederic Tudor, the "Ice King", who controlled the Northern ice trade. Despite these setbacks, Gorrie was able to obtain support from a New York businessman, who funded the construction of a large-scale version of Gorrie's ice making machine. However, just as the machine was being completed, the New York businessman died and the machine was sold at auction. This was the end of Gorrie's quest to commercialize his ice machine. Dispirited and financially ruined, Gorrie himself died soon thereafter, on June 29, 1855. He was only 51 years old.