From the Ether and Back

December 2018

Leon Theremin and his Eponymous Instrument

Leon Theremin and his Eponymous Instrument

In 1927, a poised, soft-spoken Russian scientist burst onto the world stage with a strange new instrument that shook the musical world. The instrument was an odd, yet spartan-looking device, having a horizontal loop and a vertical rod extending from an unassuming box. Standing in front of the instrument with his hands moving close to, but not touching, the loop and the rod, the Russian scientist magically created a whiny, oscillating sound that was like nothing heard before. After extensive worldwide touring with his unique instrument, the Russian scientist settled in the U.S., where he opened a research facility and socialized with the rich and famous. Then, in 1938, he disappeared as suddenly as he had appeared. He would not reappear for another 50 years. Who was this mysterious Russian scientist? He was a musician, a technical genius......and a spy. He was Lev Sergeyevich Termen, or, as he is better known in the West, Leon Theremin. And the instrument he invented was the eponymous Theremin, the predecessor of the modern synthesizer. Read on to learn more, its a Patently Interesting story!

Theremin was born in St. Petersburg, Russia on August 28, 1896 into a family of minor nobility of French Huguenot extraction. While still in secondary school, Theremin attended the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he played the cello. He also experimented with electricity and electromagnetic waves in his home laboratory, which included a million-volt Tesla coil. After secondary school, Theremin studied physics and astronomy at the St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute. He then joined the Russian military, studying radio engineering at the Nikolayevska Military Engineering School.

After graduating from military school, Theremin spent the next three years overseeing the construction of a radio station in Saratov, which was intended to connect the Volga region to Moscow. During this time, the Russian civil war was underway and Theremin joined the Red Army (communist), which was fighting against the White Army (anti-communist). Just after the radio station became operational, Theremin was forced to destroy it so as to prevent its capture by the White Army. Despite his noble background, Theremin embraced communism because he believed it would use technology to achieve social and economic progress. Little did he know that it would end up enslaving him for a good portion of his life.

With his radio station destroyed, Theremin returned to St. Petersburg, where he took a post at the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Under the tutelage of Abram Fedorovich Ioffe, Theremin did research in a number of different fields, including X-ray analysis of crystals, hypnosis and measurement devices. His work in the latter field included experimenting with high-frequency oscillators to measure the dielectric constant of gases with high precision. This experimentation, in turn, led Theremin to explore using high-frequency oscillators as proximity detectors. Theremins work with high-frequency oscillators resulted in his development of the radio Watchman, which was the world's first motion detector, and the Theremin.

During his work with oscillators, Theremin noticed the phenomenon of "heterodyning", which occurs when two signals of close but different frequency are mixed. The mixing of the two signals creates a new signal having a frequency that is equal to the difference of the two original signals. Theremin used heterodyning to create a musical instrument he originally called the Etherphone because it was believed to make waves in the Ether,that hypothetical medium that was still thought to be everwhere and permeate everything. Later, the instrument would become known as the Theramin.

Theremin was born in St. Petersburg, Russia on August 28, 1896 into a family of minor nobility of French Huguenot extraction. While still in secondary school, Theremin attended the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he played the cello. He also experimented with electricity and electromagnetic waves in his home laboratory, which included a million-volt Tesla coil. After secondary school, Theremin studied physics and astronomy at the St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute. He then joined the Russian military, studying radio engineering at the Nikolayevska Military Engineering School.

After graduating from military school, Theremin spent the next three years overseeing the construction of a radio station in Saratov, which was intended to connect the Volga region to Moscow. During this time, the Russian civil war was underway and Theremin joined the Red Army (communist), which was fighting against the White Army (anti-communist). Just after the radio station became operational, Theremin was forced to destroy it so as to prevent its capture by the White Army. Despite his noble background, Theremin embraced communism because he believed it would use technology to achieve social and economic progress. Little did he know that it would end up enslaving him for a good portion of his life.

With his radio station destroyed, Theremin returned to St. Petersburg, where he took a post at the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Under the tutelage of Abram Fedorovich Ioffe, Theremin did research in a number of different fields, including X-ray analysis of crystals, hypnosis and measurement devices. His work in the latter field included experimenting with high-frequency oscillators to measure the dielectric constant of gases with high precision. This experimentation, in turn, led Theremin to explore using high-frequency oscillators as proximity detectors. Theremins work with high-frequency oscillators resulted in his development of the radio Watchman, which was the world's first motion detector, and the Theremin.

During his work with oscillators, Theremin noticed the phenomenon of "heterodyning", which occurs when two signals of close but different frequency are mixed. The mixing of the two signals creates a new signal having a frequency that is equal to the difference of the two original signals. Theremin used heterodyning to create a musical instrument he originally called the Etherphone because it was believed to make waves in the Ether,that hypothetical medium that was still thought to be everwhere and permeate everything. Later, the instrument would become known as the Theramin.

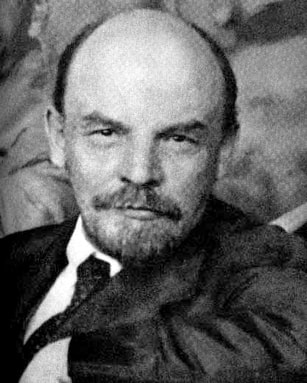

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

The Etherphone had a pair of oscillators that produced radio frequencies that were above the human range of hearing. The difference frequency caused by heterodyning, however, was in the audible range (15 to 18,000 hz). The frequency of one of the oscillators was fixed, but the frequency of the other oscillator could be changed by moving an object (such as a human hand) in the vicinity of the vertical rod-like antenna, which was connected to the oscillator. Moving an object toward the rod-like antenna would increase the difference frequency, thereby creating a higher pitch, while moving the object away from the rod-like antenna would decrease the difference frequency, thereby creating a lower pitch. Movement of an object (such as a hand) in the vicinity of the horizontal loop antenna controlled the volume, which also permitted the separation of notes.

Theremin showed the Etherphone to Professor Ioffe in October of 1920 and one month later put on a concert for engineers at the Institute. At Professor Ioffe's urging, Theramin filed a Russian patent application for the Etherphone in 1921. In that same year, Theremin played the Etherphone in two public concerts, which caught the attention of the upper eschelon of Soviet leadership, including Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, who was interested in both technology and music. In March of 1922, Theremin performed a private concert for Lenin, at his personal request. After Theremin completed his repertoire, Lenin literally jumped at the opportunity to play the Etherphone himself. After some initial help from Theremin, Lenin was able to quickly grasp the operation of the Etherphone and complete a piece of music on his own with considerable skill. Theremin was impressed "that his musical ear was keen enough to grasp the technique of the instrument so quickly".

Theremin's performance was well received by Lenin and gave him the idea to use Theremin and his instrument to promote Soviet technology. Lenin died before his idea could be put into action, but his idea did not die with him. Later that year, Theremin started touring the Soviet Union with his Etherphone. His new-found fame, particularly with the Soviet leadership, bolstered Theremin's standing within the Institute, particularly with Professor Ioffe.

Theremin showed the Etherphone to Professor Ioffe in October of 1920 and one month later put on a concert for engineers at the Institute. At Professor Ioffe's urging, Theramin filed a Russian patent application for the Etherphone in 1921. In that same year, Theremin played the Etherphone in two public concerts, which caught the attention of the upper eschelon of Soviet leadership, including Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, who was interested in both technology and music. In March of 1922, Theremin performed a private concert for Lenin, at his personal request. After Theremin completed his repertoire, Lenin literally jumped at the opportunity to play the Etherphone himself. After some initial help from Theremin, Lenin was able to quickly grasp the operation of the Etherphone and complete a piece of music on his own with considerable skill. Theremin was impressed "that his musical ear was keen enough to grasp the technique of the instrument so quickly".

Theremin's performance was well received by Lenin and gave him the idea to use Theremin and his instrument to promote Soviet technology. Lenin died before his idea could be put into action, but his idea did not die with him. Later that year, Theremin started touring the Soviet Union with his Etherphone. His new-found fame, particularly with the Soviet leadership, bolstered Theremin's standing within the Institute, particularly with Professor Ioffe.

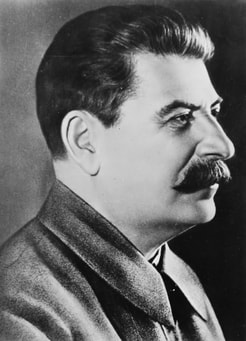

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

In the years following his meeting with Lenin, Theremin worked on a new technology that he referred to as "distance vision", which we now know as television. At this time, other scientists in the U.S., Great Britain and Germany were also working on television. By 1927, however, Theremin had pulled way ahead of the others in terms of technical advancement. His television system could be used in normal daylight, had almost instantaneous transmission-reception of an image, projected an image on a 5-by-5 foot screen and had a resolution of 100 lines. With these operating characteristics, Theremin's system permitted clear recognition of a moving person's face.

Once again, the upper eschelon of Soviet leadership became interested in a Theremin invention. This time the upper eschelon included Joseph Stalin. After being given a private demonstration of Theremin's new television system, Stalin was so impressed with the "magic screen" he decided the system should be used for border security. He also decided that the television system was too valuable to be used or disclosed publically. Henceforth, it became a state secret and was locked away from everybody, including Theremin himself. Theremin was no longer permitted to work on his television system to further improve it.

With further work on television prohibited, Therman had more time to concentrate on an endeavor he had been recruited to engage in several years earlier....espionage. Initially, Theremin's efforts were peripheral and were directed mainly towards Germany. Later, however, Theremin would be focused on the U.S. The entity within the Soviet Union that controlled Theremin's espionage activities, indeed all Soviet foreign espionage activities, was the Fourth Department of the Red Army (known as the "GRU").

Once again, the upper eschelon of Soviet leadership became interested in a Theremin invention. This time the upper eschelon included Joseph Stalin. After being given a private demonstration of Theremin's new television system, Stalin was so impressed with the "magic screen" he decided the system should be used for border security. He also decided that the television system was too valuable to be used or disclosed publically. Henceforth, it became a state secret and was locked away from everybody, including Theremin himself. Theremin was no longer permitted to work on his television system to further improve it.

With further work on television prohibited, Therman had more time to concentrate on an endeavor he had been recruited to engage in several years earlier....espionage. Initially, Theremin's efforts were peripheral and were directed mainly towards Germany. Later, however, Theremin would be focused on the U.S. The entity within the Soviet Union that controlled Theremin's espionage activities, indeed all Soviet foreign espionage activities, was the Fourth Department of the Red Army (known as the "GRU").

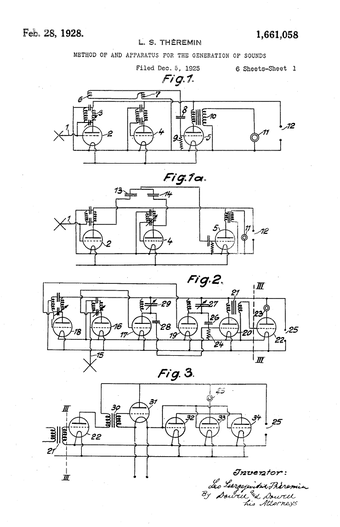

U.S. Patent No.: 1,661,058

U.S. Patent No.: 1,661,058

The Soviets were obtaining western industrial technology through the establishment of commercial arrangements with western companies. In order to make western companies more comfortable, the Soviets established front companies in western countries to give their western partners at least a superficial impression that they were dealing with a fellow western company and not the Soviets. In order to bolster their credibility, these front companies obtained patents in western countries for technology of Soviet origin. And this is where Theremin came in. He traveled to Germany to transfer technology for his watchman and Etherphone inventions to a German front company, M. J. Goldberg und Sohne GmbH, and to help them obtain patents for these inventions. Patent applications were filed for both inventions in Germany and the U.S., with U.S. Patent No.: 1,658,953 for the Watchman issuing on February 14, 1928 and U.S. Patent No.: 1,661,058 for the Etherphone issuing on February 28, 1928.

Theremin's espionage activities moved to the U.S. in 1928. The cover for his activities was the Etherphone, which was now being called the "Thereminvox" and would later be shortened to simply the "Theremin". Theremin started touring the U.S. in January of 1928, giving concerts with his instrument. The strangeness of the sound produced by the instrument, coupled with the fact that Theremin never physically touched the instrument when he played it, captivated audiences. Overnight, Theramin and his instrument were a sensation. Soon, he was moving in the highest social circles of America that included people such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and Leopold Stokowski.

Theremin used the success of his musical tour to establish commercial relations in the U.S. He helped form a series of companies to exploit his inventions, including the Patent and Process Corporation, the Migos Corporation and the Theremin Patents Corporation. All of these companies were overseen by the Amtorg Trading Corporation, which officially acted as the trade respresentive of the Soviet Union in the U.S., but clandestinely provided cover for espionage and subversive activities in the West. The Patent and Process Corporation helped negotiate a lucrative license to the Watchman and Etherphone patents between M.J. Goldberg und Sohne GmbH and RCA. These patents (and presumably the royalties from RCA) were ultimately assigned to the Theremin Patents Corporation. The money earned from licensing was used to fund Soviet propaganda and covert spying activities on behalf of the GRU.

In furtherance of his espionage activities, as well for his own personal satisfaction, Theremin conducted substantial research and development while he was in the U.S. He developed several new musical instruments, including the Rhythmicon, which was designed to play very complex rhythms, but was too temperamental to ever be commercialized. He also developed a prototype color television system, a photo-electric eye, a mirror with controllable transparency, an electronic crib alarm and the world's first metal detector, which was installed at Alcatraz prison. Theramin also did work in the field of aviation to obtain secret information on American airplane development. He found that people were more willing to divulge information if he disclosed information of his own.

In 1938, Theremin suddenly vanished. His friends suspected that he had been kidnapped by Soviet agents and brought back to the Soviet Union. There was even a rumor that he had been shot as a spy. In reality, however, Theremin went back to the Soviet Union on his own accord for several reasons. He had racked up considerable debt and wished to avoid his creditors, as well as the IRS, the Labor Department and the INS, who were all closing in on him. More importantly, he saw that war was coming and felt a duty to return to the Motherland.

The timing of Theremin's return to the Soviet Union could not have been worse. He arrived back in the Soviet Union during Stalin's Great Terror and was soon arrested and convicted of "treason to the Motherland" for detracting from the military strength of the Soviet Union and helping the international bourgeoisie. Presumably, these crimes were constituted by Theremin's activities in the U.S., even though they were undertaken at the behest of and for the benefit of the GRU. Not that it really mattered. Unlike Lenin, Stalin did not value technology and had a particular disdain for scientists and engineers, who were targeted for arrest for little or no reason.

Theremin's espionage activities moved to the U.S. in 1928. The cover for his activities was the Etherphone, which was now being called the "Thereminvox" and would later be shortened to simply the "Theremin". Theremin started touring the U.S. in January of 1928, giving concerts with his instrument. The strangeness of the sound produced by the instrument, coupled with the fact that Theremin never physically touched the instrument when he played it, captivated audiences. Overnight, Theramin and his instrument were a sensation. Soon, he was moving in the highest social circles of America that included people such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and Leopold Stokowski.

Theremin used the success of his musical tour to establish commercial relations in the U.S. He helped form a series of companies to exploit his inventions, including the Patent and Process Corporation, the Migos Corporation and the Theremin Patents Corporation. All of these companies were overseen by the Amtorg Trading Corporation, which officially acted as the trade respresentive of the Soviet Union in the U.S., but clandestinely provided cover for espionage and subversive activities in the West. The Patent and Process Corporation helped negotiate a lucrative license to the Watchman and Etherphone patents between M.J. Goldberg und Sohne GmbH and RCA. These patents (and presumably the royalties from RCA) were ultimately assigned to the Theremin Patents Corporation. The money earned from licensing was used to fund Soviet propaganda and covert spying activities on behalf of the GRU.

In furtherance of his espionage activities, as well for his own personal satisfaction, Theremin conducted substantial research and development while he was in the U.S. He developed several new musical instruments, including the Rhythmicon, which was designed to play very complex rhythms, but was too temperamental to ever be commercialized. He also developed a prototype color television system, a photo-electric eye, a mirror with controllable transparency, an electronic crib alarm and the world's first metal detector, which was installed at Alcatraz prison. Theramin also did work in the field of aviation to obtain secret information on American airplane development. He found that people were more willing to divulge information if he disclosed information of his own.

In 1938, Theremin suddenly vanished. His friends suspected that he had been kidnapped by Soviet agents and brought back to the Soviet Union. There was even a rumor that he had been shot as a spy. In reality, however, Theremin went back to the Soviet Union on his own accord for several reasons. He had racked up considerable debt and wished to avoid his creditors, as well as the IRS, the Labor Department and the INS, who were all closing in on him. More importantly, he saw that war was coming and felt a duty to return to the Motherland.

The timing of Theremin's return to the Soviet Union could not have been worse. He arrived back in the Soviet Union during Stalin's Great Terror and was soon arrested and convicted of "treason to the Motherland" for detracting from the military strength of the Soviet Union and helping the international bourgeoisie. Presumably, these crimes were constituted by Theremin's activities in the U.S., even though they were undertaken at the behest of and for the benefit of the GRU. Not that it really mattered. Unlike Lenin, Stalin did not value technology and had a particular disdain for scientists and engineers, who were targeted for arrest for little or no reason.

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Beria

Theremin was sentenced to eight years of hard labor and shipped off to Magadan, a gold-mining camp above the Arctic Circle in the Kolyma region, where temperatures dipped down to as low as -94º F. Millions of prisoners perished in the labor camps of the Kolyma region and very few ever returned. Theremin was one of these lucky few. While Stalin did not value technology or men of science, his chief of secret police, Lavrentiy Beria, did. In addition to being the head of the Soviet Union's security and secret police apparatus (NKVD), Beria also ran the Soviet Union's atomic research program and was always looking for scientific talent. Beria had Theremin transferred out of Magadan and eventually to a facility in Kuchino, near Moscow, which was a "sharaska", a minimum security facility where secret research and development was conducted. It was here that Theremin made his most infamous invention, the "Thing", a covert listening device that was so advanced that when it was finally detected (by accident) it shook America's intelligence community to its core.

Theremin developed the Thing in response to a personal order from Beria, who wanted a listening device that could not be found by conventional detection methods. What Theremin came up with was a device that had no wires, no conventional microphone, no active electronic components and no power supply. The Thing was comprised of a passive cavity resonator connected to a small quarter wavelength antenna. The passive cavity resonator was cylindrical and had a front end closed by a very thin conductive membrane. Inside, the antenna was connected to a small end disc disposed at a right angle to the membrane. A flat plate at the end of a movable tuning post was spaced from the membrane. The flat plate, together with the membrane, formed a variable capacitor that acted as a condenser microphone. The variable capacitor could be adjusted (tuned) by moving the tuning post to change the distance between the flat plate and the membrane.

Theremin developed the Thing in response to a personal order from Beria, who wanted a listening device that could not be found by conventional detection methods. What Theremin came up with was a device that had no wires, no conventional microphone, no active electronic components and no power supply. The Thing was comprised of a passive cavity resonator connected to a small quarter wavelength antenna. The passive cavity resonator was cylindrical and had a front end closed by a very thin conductive membrane. Inside, the antenna was connected to a small end disc disposed at a right angle to the membrane. A flat plate at the end of a movable tuning post was spaced from the membrane. The flat plate, together with the membrane, formed a variable capacitor that acted as a condenser microphone. The variable capacitor could be adjusted (tuned) by moving the tuning post to change the distance between the flat plate and the membrane.

Replica of the Great Seal with the Thing Mounted Inside

Replica of the Great Seal with the Thing Mounted Inside

The Thing was mounted inside a large wooden wall plaque that was carved into a relief of the Great Seal of the United States. The membrane was located just under the beak of the eagle in the Great Seal, behind a very thin veneer of wood, which allowed sound waves to reach the membrane. On July 4, 1945, the wall plaque was presented as a gift to the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Averell Harriman, who proceeded to mount the wall plaque on a wall above his desk in the office of his residence, the Spaso House. Routine X-ray screening and physical inspection of the wall plaque failed to detect the Thing, which is not surprising.

The Thing was a passive device and did not become active until a very high frequency (330 MHz) radio signal was directed at its antenna, usually from a van parked outside the Spaso House. The radio signal, modulated by sound in the office, would be reflected back to its source (e.g. the van). More specifically, sound waves (such as voices in the office) vibrated the membrane of the Thing to change the capacitance of the variable capacitor and thus the antenna. This change in capacitance modulated the radio signal that was reflected back to the source. A receiver at the source would then demodulate the reflected signal to reproduce the sound in the office.

The Thing performed as it was intended. It enabled the Soviets to listen in on sensitive conversations held in the U.S. ambassador's office, which was an invaluable source of information during the ensuing Cold War. Due its advanced nature and its sparing use by the Soviets, the Thing remained undetected for seven years. Only in 1952 was it detected after a British radio operator at the British embassy allegedly overheard American conversations on an open radio channel. The discovery of the Thing sent shock waves through America's intelligence community. The Thing showed that the Soviets had achieved a level of technical sophistication that was thought to be impossible. In comparison, the CIA, at the time, was still using conventional telephone company hardware and audio equipment utilized by local law enforcement.

Theremin's next assignment from Beria was even more audacious. In 1947, Beria charged Theremin with the task of developing another wireless surveillance system, but this time there could be no physical device planted at the target site. The project was given the codename "Buran" (meaning snowstorm). Once again, Theremin embraced the challenge. He developed an advanced listening system that used the glass of an ordinary window as the listening device. Theremin closely inspected the window at the target site to determine the precise spot where the window had optimum resonance. A beam of infrared light was then directed on the spot. Sound (such as voices) at the target site would cause the glass to vibrate and modulate the light that was impinging on the window. The modulated light was reflected back to receiving equipment (which included an interferometer and a photo element) that was operable to convert the modulated light back to sound.

Beria effectively used the Buran listening system on the American, British and French embassies. Incredibly, he also used it on his own boss: Stalin himself. Like many others within Stalin's inner circle, Beria noticed Stalin's increasing paranoia toward his subordinates and feared that Stalin would eventually turn on him. By eavesdropping on Stalin, Beria hoped to obtain advance notice of any such move.

For Theremin's work on the Thing and the Buran listening system, he secretly received the Stalin Prize, first class. Ironically, Stalin personally directed that Theremin should receive the first-class version of the prize. At about the same time, Theremin was formally released from prison. Not much changed though. He continued to do secret work for the Soviet state. And in this capacity, his life was very restricted. He could not travel outside of Moscow, he was not allowed to contact relatives or friends and he was always accompanied by bodyguards. Indeed, his very existence was a state secret.

It was not until the late 1960s that the West became aware that Theremin was still alive. And only in 1989 was Theremin again allowed to leave the Soviet Union to attend an experimental music festival in France. This trip was followed by a trip to Stockholm, Sweden in 1990, where Theremin was a guest performer at their Electronic Music Festival. By this time, Theremin realized that his eponymous instrument from the 1920's had launched an entirely new genre of music. In the 1960s, Robert Moog, who started his career building Theremins, invented the modern synthesizer, which became widely adopted by musicians throughout the world.

While the Theremin never became as popular as the Moog synthesizer, it did have its day in the sun. In the 1940s and 1950s, the Theremin, with its eerie Ooooh-EEEEE-oooooh sound, was widely used in science fiction and suspense movies to signal impending danger or strangeness. For example, it was used in the 1945 landmark film "The Lost Weekend", with Ray Milland. The Theremin was also used throughout the 1951 sci-fi classic, "The Day the Earth Stood Still", often accompanying the appearance of the alien Klaatu and his robot companion Gort.

Perhaps even more enduring than its use in classic movies, was the Theremin's use in a number of popular rock songs in the 1960's and 1970's. These songs included "Whole Lotta Love" by Led Zeppelin and "Good Vibrations" by the Beach Boys, both of which still get extensive air play on classic rock radio stations.

A final testament to the originality of the Theremin is that to this day, the Theremin remains the only musical instrument that is played without any physical human contact.

The Thing was a passive device and did not become active until a very high frequency (330 MHz) radio signal was directed at its antenna, usually from a van parked outside the Spaso House. The radio signal, modulated by sound in the office, would be reflected back to its source (e.g. the van). More specifically, sound waves (such as voices in the office) vibrated the membrane of the Thing to change the capacitance of the variable capacitor and thus the antenna. This change in capacitance modulated the radio signal that was reflected back to the source. A receiver at the source would then demodulate the reflected signal to reproduce the sound in the office.

The Thing performed as it was intended. It enabled the Soviets to listen in on sensitive conversations held in the U.S. ambassador's office, which was an invaluable source of information during the ensuing Cold War. Due its advanced nature and its sparing use by the Soviets, the Thing remained undetected for seven years. Only in 1952 was it detected after a British radio operator at the British embassy allegedly overheard American conversations on an open radio channel. The discovery of the Thing sent shock waves through America's intelligence community. The Thing showed that the Soviets had achieved a level of technical sophistication that was thought to be impossible. In comparison, the CIA, at the time, was still using conventional telephone company hardware and audio equipment utilized by local law enforcement.

Theremin's next assignment from Beria was even more audacious. In 1947, Beria charged Theremin with the task of developing another wireless surveillance system, but this time there could be no physical device planted at the target site. The project was given the codename "Buran" (meaning snowstorm). Once again, Theremin embraced the challenge. He developed an advanced listening system that used the glass of an ordinary window as the listening device. Theremin closely inspected the window at the target site to determine the precise spot where the window had optimum resonance. A beam of infrared light was then directed on the spot. Sound (such as voices) at the target site would cause the glass to vibrate and modulate the light that was impinging on the window. The modulated light was reflected back to receiving equipment (which included an interferometer and a photo element) that was operable to convert the modulated light back to sound.

Beria effectively used the Buran listening system on the American, British and French embassies. Incredibly, he also used it on his own boss: Stalin himself. Like many others within Stalin's inner circle, Beria noticed Stalin's increasing paranoia toward his subordinates and feared that Stalin would eventually turn on him. By eavesdropping on Stalin, Beria hoped to obtain advance notice of any such move.

For Theremin's work on the Thing and the Buran listening system, he secretly received the Stalin Prize, first class. Ironically, Stalin personally directed that Theremin should receive the first-class version of the prize. At about the same time, Theremin was formally released from prison. Not much changed though. He continued to do secret work for the Soviet state. And in this capacity, his life was very restricted. He could not travel outside of Moscow, he was not allowed to contact relatives or friends and he was always accompanied by bodyguards. Indeed, his very existence was a state secret.

It was not until the late 1960s that the West became aware that Theremin was still alive. And only in 1989 was Theremin again allowed to leave the Soviet Union to attend an experimental music festival in France. This trip was followed by a trip to Stockholm, Sweden in 1990, where Theremin was a guest performer at their Electronic Music Festival. By this time, Theremin realized that his eponymous instrument from the 1920's had launched an entirely new genre of music. In the 1960s, Robert Moog, who started his career building Theremins, invented the modern synthesizer, which became widely adopted by musicians throughout the world.

While the Theremin never became as popular as the Moog synthesizer, it did have its day in the sun. In the 1940s and 1950s, the Theremin, with its eerie Ooooh-EEEEE-oooooh sound, was widely used in science fiction and suspense movies to signal impending danger or strangeness. For example, it was used in the 1945 landmark film "The Lost Weekend", with Ray Milland. The Theremin was also used throughout the 1951 sci-fi classic, "The Day the Earth Stood Still", often accompanying the appearance of the alien Klaatu and his robot companion Gort.

Perhaps even more enduring than its use in classic movies, was the Theremin's use in a number of popular rock songs in the 1960's and 1970's. These songs included "Whole Lotta Love" by Led Zeppelin and "Good Vibrations" by the Beach Boys, both of which still get extensive air play on classic rock radio stations.

A final testament to the originality of the Theremin is that to this day, the Theremin remains the only musical instrument that is played without any physical human contact.

Proudly powered by Weebly