Photography Apparatus for Using Flash Powder

Photography Apparatus for Using Flash Powder

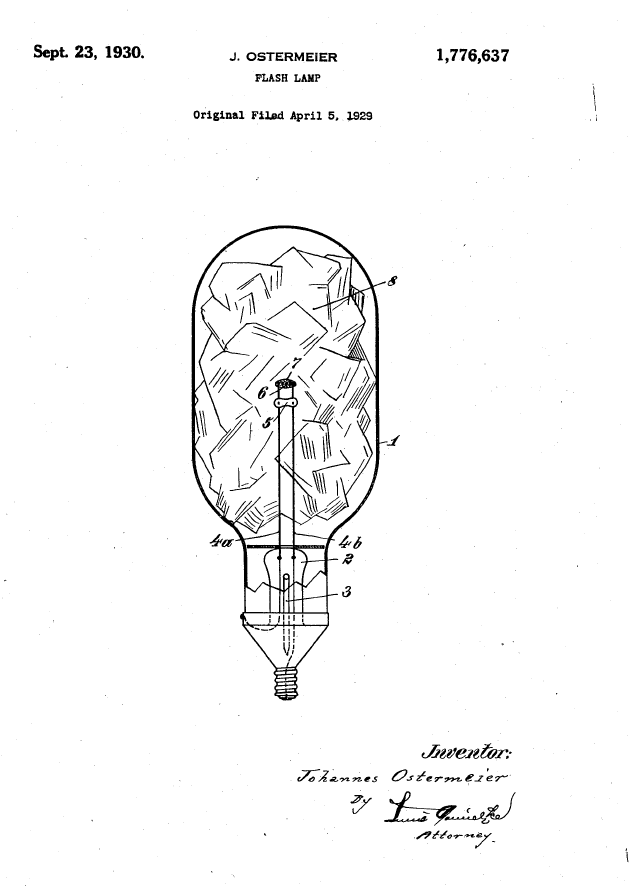

On September 23 of the year 1930, U.S. Patent No.: 1,776,637 for "Flash Lamp" issued to Johannes Ostermeier of Althegnenberg, Germany. The '637 patent covered the first commercially sold flash bulb. For most photographers, the flash bulb was a welcome innovation that greatly expanded the reach of photography, especially amateur photography. As such, the flash bulb became an instant commercial success and its annual sales quickly climbed into the millions. Today, however, the flash bulb is, for the most part, no longer used, having been replaced by the electronic flash. The last flash bulbs were manufactured in the 1980s and now are only curios of a bygone era.

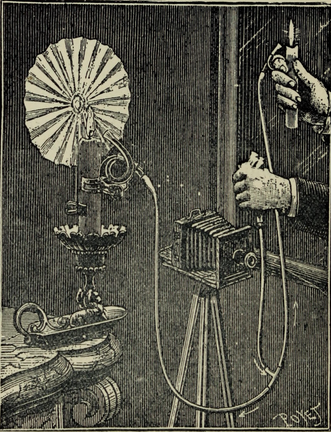

The flash bulb was invented to replace flash powder, which first appeared in the 1860s. The early flash powder was quite dangerous and resulted in the death of a number of photographers. It also generated a loud noise and copious amounts of smoke when it was ignited. The safety and usefulness of flash powder was greatly improved in 1887 when German inventors Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke invented a stable flash powder called Blitzlicht, which was a mixture of magnesium powder and potassium chlorate. Blitzlicht became widely used and allowed photographers to take "flash" pictures without generating mini-explosions, accompanied with huge amounts of white smoke. Blitzlicht, however, still had its disadvantages; it still generated smoke and was still somewhat dangerous if not handled properly. These disadvantages prompted Austrian inventor Paul Vierkotter to develop an alternative.

What Vierkotter came up with was the flash bulb. In Vierkotter's flash bulb, a small charge of flash powder was mixed with an oxygen-generating substance (such as manganese peroxide) and was enclosed in a glass bulb that was mostly evacuated. An ignition wire contacted the flash powder mixture and was conductively connected to a metal disk on a threaded bottom fitting of the flash bulb. When current was supplied to the metal disk, the ignition wire heated up and ignited the flash powder mixture to create a flash of light. For his efforts, Vierkotter was awarded U.S. Patent No.: 1,625,108, which issued on April 19, 1927 and claimed priority from a corresponding German patent application that was filed on August 15, 1925. Vierkotter's patent was assigned to Hauser & Co. of Augsberg, Germany.

Vierkotter's flash bulb was designed to have the explosion of the flash powder mixture occur in a (substantial) vacuum so as to not create an overpressure that would shatter the glass bulb, i.e., the explosion was contained within the glass bulb. The major flaw in Vierkotter's design was its reliance on the seal of the glass bulb. If air leaked into the glass bulb and the flash bulb was then actuated, it would explode and injure anyone close by.

The risks presented by the Vierkotter flash bulb dissuaded Hauser & Co. from commercially selling it. Instead, they engaged Ostermeier as a consulting engineer to develop a safer flash bulb. Not long after he was engaged, Ostermeier came up with his design for a flash bulb, which became the subject of the '637 patent. The Ostermeier flash bulb was similar to Vierkotter's, except the glass bulb was filled with very thin (about 0.0005mm) strips of aluminum foil. In addition, the bulb contained pure oxygen at subatmospheric pressure. The beauty of this design was that aluminum foil would create a blinding flash when it was ignited in a pure oxygen atmosphere, but would burn very slowly, if at all, in regular air. Thus, if the seal of the bulb leaked and air was allowed to enter the bulb, actuation of the flash bulb would not cause it to explode. It wouldn't work, but at least it didn't pose a risk of physical harm.

Ostermeier's '637 patent was assigned to the General Electric Company, which started selling Ostermeier's flash bulb (first in England in 1929 and later in the U.S.) under the trademark SASHALITE. The trademark was a homage to the famous London photographer Sasha, who presumably endorsed the flash bulb. Sasha, whose real name was Alexander Stewart, was himself a technical pioneer who made a number of inventions in the field of photography, particularly with regard to lighting. Indeed, he invented a flash system that allowed him to create dramatic lighting effects that became one of his hallmarks. Unsurprisingly, he called his system the Sashalite System. A component of this system was a device that synchronized the opening of a camera shutter with the actuation of a flash bulb, such as the SASHALITE flash bulb. Sasha received U.S. Patent No. 1,995,552 for this device.

Three years after General Electric started selling the SASHALITE flash bulb, Osram Licht AG of Germany started selling the Ostermeier flash bulb in Germany under the trademark VACUBLITZ.

The SASHALITE and VACUBLITZ flash bulbs allowed amateur photographers to practice flash photography with minimal expense and without much difficulty. In effect, these flash bulbs opened up a complete new field for amateur photography. In the realm of professional photography, the flash bulbs allowed pictures to be taken in places where the use of flash powder had been either impracticable or prohibited.

The flash bulb was invented to replace flash powder, which first appeared in the 1860s. The early flash powder was quite dangerous and resulted in the death of a number of photographers. It also generated a loud noise and copious amounts of smoke when it was ignited. The safety and usefulness of flash powder was greatly improved in 1887 when German inventors Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke invented a stable flash powder called Blitzlicht, which was a mixture of magnesium powder and potassium chlorate. Blitzlicht became widely used and allowed photographers to take "flash" pictures without generating mini-explosions, accompanied with huge amounts of white smoke. Blitzlicht, however, still had its disadvantages; it still generated smoke and was still somewhat dangerous if not handled properly. These disadvantages prompted Austrian inventor Paul Vierkotter to develop an alternative.

What Vierkotter came up with was the flash bulb. In Vierkotter's flash bulb, a small charge of flash powder was mixed with an oxygen-generating substance (such as manganese peroxide) and was enclosed in a glass bulb that was mostly evacuated. An ignition wire contacted the flash powder mixture and was conductively connected to a metal disk on a threaded bottom fitting of the flash bulb. When current was supplied to the metal disk, the ignition wire heated up and ignited the flash powder mixture to create a flash of light. For his efforts, Vierkotter was awarded U.S. Patent No.: 1,625,108, which issued on April 19, 1927 and claimed priority from a corresponding German patent application that was filed on August 15, 1925. Vierkotter's patent was assigned to Hauser & Co. of Augsberg, Germany.

Vierkotter's flash bulb was designed to have the explosion of the flash powder mixture occur in a (substantial) vacuum so as to not create an overpressure that would shatter the glass bulb, i.e., the explosion was contained within the glass bulb. The major flaw in Vierkotter's design was its reliance on the seal of the glass bulb. If air leaked into the glass bulb and the flash bulb was then actuated, it would explode and injure anyone close by.

The risks presented by the Vierkotter flash bulb dissuaded Hauser & Co. from commercially selling it. Instead, they engaged Ostermeier as a consulting engineer to develop a safer flash bulb. Not long after he was engaged, Ostermeier came up with his design for a flash bulb, which became the subject of the '637 patent. The Ostermeier flash bulb was similar to Vierkotter's, except the glass bulb was filled with very thin (about 0.0005mm) strips of aluminum foil. In addition, the bulb contained pure oxygen at subatmospheric pressure. The beauty of this design was that aluminum foil would create a blinding flash when it was ignited in a pure oxygen atmosphere, but would burn very slowly, if at all, in regular air. Thus, if the seal of the bulb leaked and air was allowed to enter the bulb, actuation of the flash bulb would not cause it to explode. It wouldn't work, but at least it didn't pose a risk of physical harm.

Ostermeier's '637 patent was assigned to the General Electric Company, which started selling Ostermeier's flash bulb (first in England in 1929 and later in the U.S.) under the trademark SASHALITE. The trademark was a homage to the famous London photographer Sasha, who presumably endorsed the flash bulb. Sasha, whose real name was Alexander Stewart, was himself a technical pioneer who made a number of inventions in the field of photography, particularly with regard to lighting. Indeed, he invented a flash system that allowed him to create dramatic lighting effects that became one of his hallmarks. Unsurprisingly, he called his system the Sashalite System. A component of this system was a device that synchronized the opening of a camera shutter with the actuation of a flash bulb, such as the SASHALITE flash bulb. Sasha received U.S. Patent No. 1,995,552 for this device.

Three years after General Electric started selling the SASHALITE flash bulb, Osram Licht AG of Germany started selling the Ostermeier flash bulb in Germany under the trademark VACUBLITZ.

The SASHALITE and VACUBLITZ flash bulbs allowed amateur photographers to practice flash photography with minimal expense and without much difficulty. In effect, these flash bulbs opened up a complete new field for amateur photography. In the realm of professional photography, the flash bulbs allowed pictures to be taken in places where the use of flash powder had been either impracticable or prohibited.