The Confidential Clerk

May 2018

In 1854, the fifth Commissioner of Patents, Charles Mason, hired a confidential clerk to oversee the work of his other clerks, some of whom were improperly disclosing the contents of patent applications to third parties for personal gain. With the oversight of Commissioner Mason’s confidential clerk, this unsavory practice quickly stopped. Who you may ask was this confidential clerk? Well, it was none other than Clara Barton, the future founder of the American Red Cross. Read on to learn more; its a Patently Interesting story!

Clara Barton

Clara Barton

After an initially promising, but ultimately disappointing stint at a public school in New Jersey, Clara Barton headed south to Washington, D.C. in 1854. Through her friend Alexander Dewitt, a congressman from her home district, Clara met Charles Mason, the Commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office. Mason was impressed with Clara and asked her to become governess for his twelve year old daughter. Before the arrangement could be finalized, however, DeWitt convinced Mason that Clara would be better suited as a clerk in the Patent Office. At the time, there were no female clerks in the Patent Office. Indeed, there were no women working in regular office positions in the federal government. It came as a bit of a surprise then when Charles Mason’s carriage pulled up in front of Clara’s boarding house one day and the driver requested her to get in and travel down to the Patent Office for an interview.

After dispensing with formalities, Mason quickly came to the point of the interview. He asked Clara whether she knew of a man of perfect integrity and trustworthiness who could do some important work for him in discovering where frauds had been perpetrated in his accounts. Clara told him that she knew of no such man, but that she did know a woman who could exactly serve him. Mason told Clara to send for this woman, which, needless to say, didn’t take long. Mason was clearly pleased with Clara’s interest in the position and asked her when she could start. Clara replied “when you choose”. How about now? responded Mason. Clara said “certainly”, took off her travel shawl and immediately set to work. And thus began Clara’s career as a (confidential) patent clerk.

Clara began her work at the Patent Office as a recording clerk, which is presumably where the frauds were occurring. In doing so, Clara became the first woman to work in a regular office position in the federal government. Even better, she was paid the same wages as her male co-workers. These wages were $1,400 per year, which at the time was near the top for a clerical salary. Soon, Clara was joined by other female clerks, who were hired by Mason.

Initially, Clara was happy at the Patent Office. She was well paid and the work was intellectually stimulating, if not exciting. Perhaps most importantly, she was treated fairly, which can be attributed to Commissioner Mason, who was known as a fair and honest man.

After dispensing with formalities, Mason quickly came to the point of the interview. He asked Clara whether she knew of a man of perfect integrity and trustworthiness who could do some important work for him in discovering where frauds had been perpetrated in his accounts. Clara told him that she knew of no such man, but that she did know a woman who could exactly serve him. Mason told Clara to send for this woman, which, needless to say, didn’t take long. Mason was clearly pleased with Clara’s interest in the position and asked her when she could start. Clara replied “when you choose”. How about now? responded Mason. Clara said “certainly”, took off her travel shawl and immediately set to work. And thus began Clara’s career as a (confidential) patent clerk.

Clara began her work at the Patent Office as a recording clerk, which is presumably where the frauds were occurring. In doing so, Clara became the first woman to work in a regular office position in the federal government. Even better, she was paid the same wages as her male co-workers. These wages were $1,400 per year, which at the time was near the top for a clerical salary. Soon, Clara was joined by other female clerks, who were hired by Mason.

Initially, Clara was happy at the Patent Office. She was well paid and the work was intellectually stimulating, if not exciting. Perhaps most importantly, she was treated fairly, which can be attributed to Commissioner Mason, who was known as a fair and honest man.

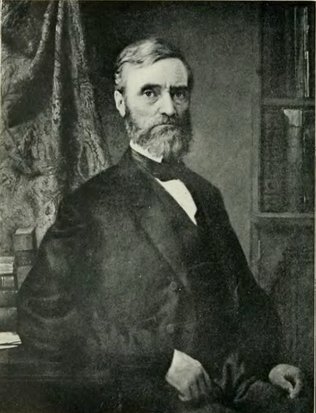

Charles Mason

Charles Mason

Mason had been appointed Patent Commissioner in 1853 by President Franklin Pierce and had came to the Patent Office with a distinguished academic and legal background. He attended West Point, graduating first in his class in 1829, ahead of Robert E. Lee, who graduated 2nd. After graduation, Mason remained at West Point for several years, teaching engineering. Later, he became a lawyer and then the Chief Justice of the Iowa Supreme Court.

At the outset of his tenure as Patent Commissioner, Mason was confronted with the bribery of his patent examiners. At least one detailed record from that time describes how a bribe was blatantly offered to one of Mason’s examiners in writing via the mail. Mason also described the problem in his 1853 report to Congress and urged that some form of punishment should be visited upon transgressors to curb the problem. These two records suggest that bribery in the Patent Office may have been commonplace before Mason became Patent Commissioner. Mason, however, did not tolerate such behavior and quickly moved to squelch it.

Now, with the arrival of Clara at the Patent Office, Mason could pursue the frauds that were being committed by his clerks. They were selling access to patent applications and caveats, which were supposed to be kept secret. Clara found the frauds and Mason quickly put an end to them. Unfortunately, Clara paid the price for the success of this operation. Her exposure of the frauds made her unpopular with the other (male) clerks. As she later recalled: “they tried to make the place too hard for me. It wasn’t a pleasant experience; in fact it was very trying….” The clerks would blow smoke at her, spit tobacco in front of her and greet her with catcalls and derogatory remarks.

Clara’s situation worsened considerably when Commissioner Mason left the Patent Office in July of 1855 and went back home to Iowa to tend to his farm. Mason’s departure had been precipitated, at least partially, by the Secretary of the Interior, Robert McClelland, who was interfering in Mason’s administration of the Patent Office, particularly with regard to personnel. Mason was replaced by his assistant, Samuel T. Shuger, who tried to curry favor with McClellan by persecuting the women clerks. McClelland was an old fashioned politician who didn’t think that women should be working together with men. Shuger removed Clara and the other women from their roles as clerks and made them copyists, where they were paid ten cents per hundred words. This move was not just a demotion in rank, but also in pay. The most industrious copyist could at most make $900 per year. Even this amount soon became unattainable because Shuger saw to it that Clara and the other female copyists received no work. When Mason heard that the female clerks had been dismissed, he was not happy, stating that “I shall have some grave objections if I understand the matter rightly. They were some of my best clerks and besides, charity dictated their appointment and retention”.

At the outset of his tenure as Patent Commissioner, Mason was confronted with the bribery of his patent examiners. At least one detailed record from that time describes how a bribe was blatantly offered to one of Mason’s examiners in writing via the mail. Mason also described the problem in his 1853 report to Congress and urged that some form of punishment should be visited upon transgressors to curb the problem. These two records suggest that bribery in the Patent Office may have been commonplace before Mason became Patent Commissioner. Mason, however, did not tolerate such behavior and quickly moved to squelch it.

Now, with the arrival of Clara at the Patent Office, Mason could pursue the frauds that were being committed by his clerks. They were selling access to patent applications and caveats, which were supposed to be kept secret. Clara found the frauds and Mason quickly put an end to them. Unfortunately, Clara paid the price for the success of this operation. Her exposure of the frauds made her unpopular with the other (male) clerks. As she later recalled: “they tried to make the place too hard for me. It wasn’t a pleasant experience; in fact it was very trying….” The clerks would blow smoke at her, spit tobacco in front of her and greet her with catcalls and derogatory remarks.

Clara’s situation worsened considerably when Commissioner Mason left the Patent Office in July of 1855 and went back home to Iowa to tend to his farm. Mason’s departure had been precipitated, at least partially, by the Secretary of the Interior, Robert McClelland, who was interfering in Mason’s administration of the Patent Office, particularly with regard to personnel. Mason was replaced by his assistant, Samuel T. Shuger, who tried to curry favor with McClellan by persecuting the women clerks. McClelland was an old fashioned politician who didn’t think that women should be working together with men. Shuger removed Clara and the other women from their roles as clerks and made them copyists, where they were paid ten cents per hundred words. This move was not just a demotion in rank, but also in pay. The most industrious copyist could at most make $900 per year. Even this amount soon became unattainable because Shuger saw to it that Clara and the other female copyists received no work. When Mason heard that the female clerks had been dismissed, he was not happy, stating that “I shall have some grave objections if I understand the matter rightly. They were some of my best clerks and besides, charity dictated their appointment and retention”.

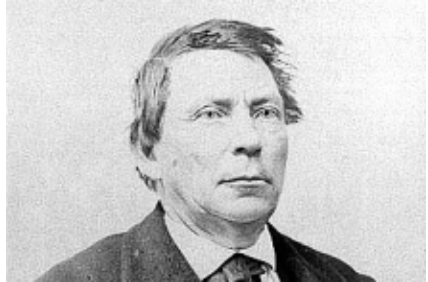

Robert McClelland

Robert McClelland

Clara did not take her demotion lying down. She contacted her friend DeWitt and informed him of what Shuger was doing. Dewitt, in turn, wrote McClelland a letter, requesting that Clara be allowed to continue working at the Patent Office. McClelland, however, was unmoved. He rebuffed DeWitt’s request, stating that “There is every disposition on my part to do anything for the lady in question except to retain her, or any of the other females at work in the rooms of the Patent Office.” McClelland explained that he had no objection to the Patent Office employing females, but they had to work at home. It was his firm conviction that “there is such an obvious impropriety in the mixing of the two sexes within the walls of a public office, that I am determined to arrest the practice…..”

At this point, Clara’s situation looked bleak. However, Mason’s departure from the Patent Office had caused an uproar amongst individual inventors, who viewed him as their champion. Petitions were sent to both Mason and the Patent Office requesting that he return to the Patent Office and be reinstated as Patent Commissioner. These efforts were successful and resulted in Mason returning to Washington in November of 1855 and reassuming his position as Patent Commissioner. Of course, this was good news for Clara.

Upon his return, Mason was able to increase Clara’s pay to what it was before his departure, but he could not reinstate Clara as a records clerk or permit Clara and the other women to work on the Patent Office premises on a daily basis. Apparently, McClelland was too obstinate and Mason did not want to engage in a protracted battle with him over the issue. Besides, Mason had other problems to deal with, one of them being intemperance among his clerks and examiners. The problem of drunkenness was exasperated by the fact that some of the offenders were prominent political appointees. One of the worst was a protege of the President (Franklin Pierce), who Mason suspended for being “beastly drunk”. Upon hearing of the suspension, the President implored Mason to “try him once more”. Needless to say, this rankled Mason, who felt that such favoritism impaired discipline in the office.

Mason’s departure and return to the Patent Office did not stop McClelland from interfering in the operations of the Patent Office. Indeed, McClelland became such a nuisance that Mason could not perform the duties he was tasked by Congress to perform. McClelland’s constant interference forced Mason to again tender his resignation in September of 1856. This time, however, the President personally intervened and gave Mason full control of the Patent Office, which persuaded Mason to stay on as Patent Commissioner.

1857 ushered in the Democratic Buchanan administration, which demanded total political fealty from all government employees. Mason knew his days were numbered when he revealed that he did not agree with this policy, even though he himself was a Democrat. Clara also felt vulnerable after she let it slip that she supported John C. Fremont, who had opposed Buchanan as the first presidential candidate of the new Republican Party. Soon, Clara was pejoratively being called a “Black Republican” by other employees of the Patent Office.

Eventually, events came to a head later in 1857. Mason was forced to resign in July of 1857 after refusing to discharge several examiners he thought highly of, but were presumably of the wrong political persuasion. Several months later, Clara quit as well. As she later recalled: “I was told that my place was wanted, and I was very willing to give it up”.

Clara’s departure from the Patent Office in 1857 was not the end of her career at the Patent Office. Less than four years later, Abraham Lincoln became President and all of a sudden her politics were no longer so offensive. The same people who had previously asked Clara to leave were now begging her to return. So she did, in the Spring of 1861, albeit as a temporary clerk.

At this point, Clara’s situation looked bleak. However, Mason’s departure from the Patent Office had caused an uproar amongst individual inventors, who viewed him as their champion. Petitions were sent to both Mason and the Patent Office requesting that he return to the Patent Office and be reinstated as Patent Commissioner. These efforts were successful and resulted in Mason returning to Washington in November of 1855 and reassuming his position as Patent Commissioner. Of course, this was good news for Clara.

Upon his return, Mason was able to increase Clara’s pay to what it was before his departure, but he could not reinstate Clara as a records clerk or permit Clara and the other women to work on the Patent Office premises on a daily basis. Apparently, McClelland was too obstinate and Mason did not want to engage in a protracted battle with him over the issue. Besides, Mason had other problems to deal with, one of them being intemperance among his clerks and examiners. The problem of drunkenness was exasperated by the fact that some of the offenders were prominent political appointees. One of the worst was a protege of the President (Franklin Pierce), who Mason suspended for being “beastly drunk”. Upon hearing of the suspension, the President implored Mason to “try him once more”. Needless to say, this rankled Mason, who felt that such favoritism impaired discipline in the office.

Mason’s departure and return to the Patent Office did not stop McClelland from interfering in the operations of the Patent Office. Indeed, McClelland became such a nuisance that Mason could not perform the duties he was tasked by Congress to perform. McClelland’s constant interference forced Mason to again tender his resignation in September of 1856. This time, however, the President personally intervened and gave Mason full control of the Patent Office, which persuaded Mason to stay on as Patent Commissioner.

1857 ushered in the Democratic Buchanan administration, which demanded total political fealty from all government employees. Mason knew his days were numbered when he revealed that he did not agree with this policy, even though he himself was a Democrat. Clara also felt vulnerable after she let it slip that she supported John C. Fremont, who had opposed Buchanan as the first presidential candidate of the new Republican Party. Soon, Clara was pejoratively being called a “Black Republican” by other employees of the Patent Office.

Eventually, events came to a head later in 1857. Mason was forced to resign in July of 1857 after refusing to discharge several examiners he thought highly of, but were presumably of the wrong political persuasion. Several months later, Clara quit as well. As she later recalled: “I was told that my place was wanted, and I was very willing to give it up”.

Clara’s departure from the Patent Office in 1857 was not the end of her career at the Patent Office. Less than four years later, Abraham Lincoln became President and all of a sudden her politics were no longer so offensive. The same people who had previously asked Clara to leave were now begging her to return. So she did, in the Spring of 1861, albeit as a temporary clerk.

D.P. Holloway

D.P. Holloway

While many of the faces in the Patent Office were the same, the atmosphere was different. The new Commissioner, David P. Holloway, was receptive to having women in the Patent Office, and was even rumored to enjoy their presence. There was now a women’s section in the Patent Office, which is where Clara resumed work as a temporary clerk making copies of patent documents. She was paid less than she was before under Mason, but she was happy to be back and quickly settled into her Patent Office routine.

Clara’s routine, however, was soon interrupted by the Civil War. It appeared on her doorstep, with the arrival in Washington of soldiers from her home state of Massachusetts, some of whom had been wounded during rioting in Baltimore; the first casualties of the war. Seeing how ill-prepared the government was to handle these troops, especially the wounded ones, Clara jumped into action and helped obtain food, shelter and medical care for them. Soon, additional troops from other states began to arrive in Washington, and Clara’s aid work increased. Initially, she worked to distribute care packages from families, but later she began to also actively solicit the supply of provisions from other sources. Clara’s philanthropic work increased even more dramatically after the First Battle of Bull Run, which was fought just outside of Washington and saw a large number of wounded soldiers brought back to the city. Indeed, a large number of wounded soldiers were housed in the east, west and north model halls of the Patent Office.

Clara’s routine, however, was soon interrupted by the Civil War. It appeared on her doorstep, with the arrival in Washington of soldiers from her home state of Massachusetts, some of whom had been wounded during rioting in Baltimore; the first casualties of the war. Seeing how ill-prepared the government was to handle these troops, especially the wounded ones, Clara jumped into action and helped obtain food, shelter and medical care for them. Soon, additional troops from other states began to arrive in Washington, and Clara’s aid work increased. Initially, she worked to distribute care packages from families, but later she began to also actively solicit the supply of provisions from other sources. Clara’s philanthropic work increased even more dramatically after the First Battle of Bull Run, which was fought just outside of Washington and saw a large number of wounded soldiers brought back to the city. Indeed, a large number of wounded soldiers were housed in the east, west and north model halls of the Patent Office.

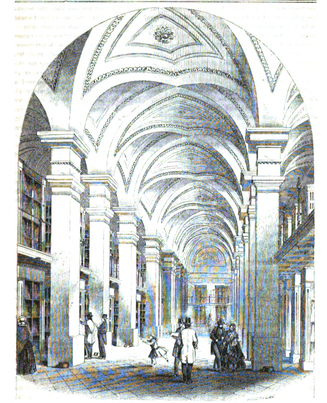

East Model Hall of Patent Office

East Model Hall of Patent Office

For a while, Clara continued to work at the Patent Office, while helping the troops. However, she became less enthusiastic about her work there, and was upset by the presence of a large number of Southern sympathizers. To make matters worse, the old scourge of theft and frauds had returned. Clara noted that these new thefts and frauds were serious enough to have deprived the Patent Office “almost totally of [its] means of support”. This was undoubtedly an exaggeration, but still, there were significant problems afoot. When Holloway became Patent Commissioner in 1861, the Patent Office had a $70,000 surplus of funds. However, in less than five months, this surplus, together with the ordinary income of the Patent Office was almost totally expended.

Revenue for Holloway’s first year dropped almost 50% from the previous year, plummeting from $256,352 to $137,354. Meanwhile, expenditures were still at a relatively high $221,492.

While the fiscal woes of the Patent Office were mostly a result of the onset of the Civil War, serious claims of fraud and mismanagement were made against Holloway. In fact, a whole of host of unsavory allegations were made against him. It was alleged that Holloway squandered Patent Office funds, used Patent Office resources for personal purposes, had unqualified clerks examining patent applications, unlawfully reduced the salaries of examiners, practiced favoritism amongst employees and padded the payroll with family and friends, who did little to no work and collected inflated salaries. Moreover, two of Holloway’s sons, who were made clerks in the Patent Office, were accused of stealing money transmitted to and from the Patent Office. The allegations against Holloway were serious enough to prompt the House of Representatives to form a committee and conduct an investigation in 1863.

The scope of the investigation was limited, however, at least in part due to a lack of funds. Nonetheless, evidence was produced supporting many of the allegations, including favoritism, the squandering of funds and theft of money by Holloway’s sons. Overall, however, the committee “failed to discover evidence to satisfy them that the Commissioner wrongfully intended to misappropriate the public money.” And with that, Holloway survived the investigation and continued to serve as Patent Commissioner until 1865.

What became clear from the evidence produced during the Congressional investigation was that Holloway had a soft spot for several of the women employed at the Patent Office, one of which was Clara. Holloway considered the women “special cases” and gave them a privilege not afforded to other, similarly-situated employees. The privilege that Holloway gave the women was that he allowed them to be absent from the Patent Office for extended periods of time, while still paying them, albeit at half pay. The arrangement was that the women’s work would be done by replacements, who would receive half of the women’s pay, while the women would retain the other half. In the past, this arrangement was afforded to other employees of the Patent Office, but never to temporary clerks, like Clara and the other women. Interestingly, Clara’s replacement was a man.

The investigating committee criticized Holloway for helping two of the women because they were Southerners, whose husbands were in the South, presumably fighting for the Confederacy. Holloway defended himself, arguing that the women were destitute with small children and had never shown any disloyalty to the Union. Holloway did not defend his special treatment of Clara because it wasn’t even questioned. Perhaps, this was because everyone knew Clara was no longer working at the Patent Office, and that, instead, she was now devoting her energies to helping provide supplies and medical care to the troops. Indeed, it appears that Clara stopped working at the Patent Office in February of 1862, but continued to receive (half) pay through the end of the war.

Even though the Congressional investigating committee did not question Holloway’s arrangement with Clara, others did. In a case of bitter irony, it was the other women in the Patent Office who complained to Holloway about Clara’s arrangement. Under the mistaken belief that the U.S. Government was paying Clara for her relief work for the Army, the women complained to Holloway and urged him to remove Clara from the Patent Office payroll. Clara responded to the women’s complaint in a highly emotional letter to Holloway that was brimming with hurt and anger. Clara forcefully denied the allegation that she was being paid for her Army relief work, stating: “This assertion…is utterly and entirely and I fear willfully and maliciously false….” Revealing an inner hurt, she commented that “It has been a part of the work of my life-time to aid in opening every avenue to honorable employment for my own sex. I hope these ladies are equally generous with me.” At the end of her letter, Clara lashed out angrily at the women’ allegation, calling it “derogatory to every feeling of humanity and patriotism and as such I reject and scorn it.”

Holloway responded to Clara’s letter several weeks later. He assured her that her desk at the Patent Office was guaranteed for as long as he had his position, and that both of them had been misinformed. Good to his word, Holloway ensured that Clara continued to receive her (half) salary until he left the Patent Office in August of 1865. And with Holloway’s departure, Clara’s professional career as a confidential clerk at the Patent Office came to an end.

Revenue for Holloway’s first year dropped almost 50% from the previous year, plummeting from $256,352 to $137,354. Meanwhile, expenditures were still at a relatively high $221,492.

While the fiscal woes of the Patent Office were mostly a result of the onset of the Civil War, serious claims of fraud and mismanagement were made against Holloway. In fact, a whole of host of unsavory allegations were made against him. It was alleged that Holloway squandered Patent Office funds, used Patent Office resources for personal purposes, had unqualified clerks examining patent applications, unlawfully reduced the salaries of examiners, practiced favoritism amongst employees and padded the payroll with family and friends, who did little to no work and collected inflated salaries. Moreover, two of Holloway’s sons, who were made clerks in the Patent Office, were accused of stealing money transmitted to and from the Patent Office. The allegations against Holloway were serious enough to prompt the House of Representatives to form a committee and conduct an investigation in 1863.

The scope of the investigation was limited, however, at least in part due to a lack of funds. Nonetheless, evidence was produced supporting many of the allegations, including favoritism, the squandering of funds and theft of money by Holloway’s sons. Overall, however, the committee “failed to discover evidence to satisfy them that the Commissioner wrongfully intended to misappropriate the public money.” And with that, Holloway survived the investigation and continued to serve as Patent Commissioner until 1865.

What became clear from the evidence produced during the Congressional investigation was that Holloway had a soft spot for several of the women employed at the Patent Office, one of which was Clara. Holloway considered the women “special cases” and gave them a privilege not afforded to other, similarly-situated employees. The privilege that Holloway gave the women was that he allowed them to be absent from the Patent Office for extended periods of time, while still paying them, albeit at half pay. The arrangement was that the women’s work would be done by replacements, who would receive half of the women’s pay, while the women would retain the other half. In the past, this arrangement was afforded to other employees of the Patent Office, but never to temporary clerks, like Clara and the other women. Interestingly, Clara’s replacement was a man.

The investigating committee criticized Holloway for helping two of the women because they were Southerners, whose husbands were in the South, presumably fighting for the Confederacy. Holloway defended himself, arguing that the women were destitute with small children and had never shown any disloyalty to the Union. Holloway did not defend his special treatment of Clara because it wasn’t even questioned. Perhaps, this was because everyone knew Clara was no longer working at the Patent Office, and that, instead, she was now devoting her energies to helping provide supplies and medical care to the troops. Indeed, it appears that Clara stopped working at the Patent Office in February of 1862, but continued to receive (half) pay through the end of the war.

Even though the Congressional investigating committee did not question Holloway’s arrangement with Clara, others did. In a case of bitter irony, it was the other women in the Patent Office who complained to Holloway about Clara’s arrangement. Under the mistaken belief that the U.S. Government was paying Clara for her relief work for the Army, the women complained to Holloway and urged him to remove Clara from the Patent Office payroll. Clara responded to the women’s complaint in a highly emotional letter to Holloway that was brimming with hurt and anger. Clara forcefully denied the allegation that she was being paid for her Army relief work, stating: “This assertion…is utterly and entirely and I fear willfully and maliciously false….” Revealing an inner hurt, she commented that “It has been a part of the work of my life-time to aid in opening every avenue to honorable employment for my own sex. I hope these ladies are equally generous with me.” At the end of her letter, Clara lashed out angrily at the women’ allegation, calling it “derogatory to every feeling of humanity and patriotism and as such I reject and scorn it.”

Holloway responded to Clara’s letter several weeks later. He assured her that her desk at the Patent Office was guaranteed for as long as he had his position, and that both of them had been misinformed. Good to his word, Holloway ensured that Clara continued to receive her (half) salary until he left the Patent Office in August of 1865. And with Holloway’s departure, Clara’s professional career as a confidential clerk at the Patent Office came to an end.

Proudly powered by Weebly