Guglielmo Marconi with his wireless telegraphy system

Guglielmo Marconi with his wireless telegraphy system

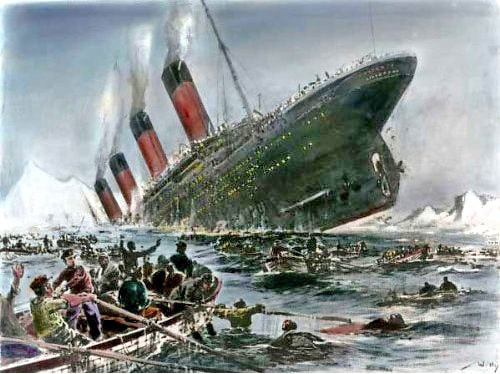

On April 15 of the year 1912, the RMS Titanic sank in the North Atlantic after hitting an iceberg, resulting in a horrific loss of life. Nearly 1,500 people out of a total of 2,201 perished in the icy waters of the Atlantic. The sinking and huge loss of life stunned the world. It was hard for people at the time to comprehend that a ship widely believed to be "unsinkable" due its modern design and up-to-date safety features could sink in less than three hours after sideswiping an iceberg. The sinking of the Titanic, however, should have served as a reminder that at any point in time, technology can always be improved and that human fallibility and plain bad luck can negate the best of technology.

Several new innovations and technologies were utilized by the Titanic, one of which was the "Marconi" wireless telegraphy system, which had been invented by Guglielmo Marconi. The Marconi system could send and receive telegraph signals (in Morse code) by radio waves. The first passenger ship to carry such a system was the RMS Lucania in June of 1901. By 1904, Marconi wireless telegraphy systems were in general use on passenger ships. The Titanic had the most up-to-date model of the "Marconi" system; it was a 5kW model with a synchronous rotary spark discharger. Nominally, the Titanic's Marconi system had a working range of 250 nautical miles, but communicating with more distant stations was possible. While the Titanic had the most modern Marconi system, it was not the best radio technology in existence at the time, but that is a story for another day.

At the time of the sailing of the Titanic, the wireless operators on passenger ships were not employees of the shipping lines that owned the ships. Instead, the wireless operators worked for one of four companies that provided wireless services to the shipping companies. In the case of the Titanic, it was the Marconi Company, which provided the services of two wireless operators. The primary responsibility of these operators was to send and receive messages for the passengers. Handling weather reports and communications from other ships were secondary.

On April 14, 1912, the Titanic received six messages from other ships warning of icebergs. The last three of these messages were not conveyed to the captain of the Titanic, Edward John Smith, or his officers because the wireless operators were too busy handling trivial messages for passengers. The last message received by the Titanic was sent at 11:00 PM by Cyril Evans, the wireless operator of the S.S. Californian, which was close to the Titanic. The message from Evans warned that: "We are stopped and surrounded by ice". The wireless operator of the Titanic, Jack Phillips, responded with "shut up, shut up, I am busy; I am working Cape Race". Phillip's rude response was prompted by a shortcoming of the Marconi wireless system.

The Marconi System used a “spark gap” transmitter that utilized a very wide band of frequencies. As such, signals being sent at the same time would interfere with each other, with stronger signals overwhelming weaker signals. At the time Evans sent his message to the Titanic, Phillips was communicating with a wireless station at Cape Rice, Newfoundland to receive personal messages, news and stock reports for passengers. Since the Californian was much closer than Cape Rice, the signal from the Californian was blocking signals from Cape Rice, which prompted Phillips to tell Evans to get off the air.

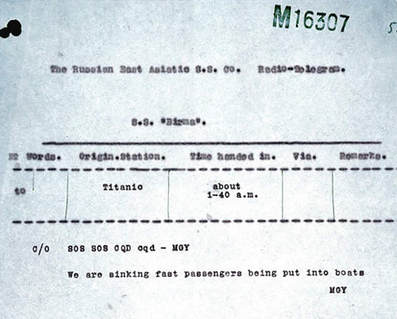

Distress Message sent by Jack Phillips

Distress Message sent by Jack Phillips

At 11:30 PM, Evans could still hear the Titanic communicating with Cape Rice, so he decided to turn off his system and go to bed. Ten minutes later, the Titanic would hit the iceberg and begin sinking. Being in bed, away from his station, Evans would miss the distress signals that were soon being sent by Phillips (one of which is shown to the left). It is entirely possible that if Phillips had not told Evans to get off the air and Evans had remained at his station, hundreds of lives may have been saved. Moreover, if all the warning messages received by the Titanic had been delivered to Captain Smith and/or his officers and they had paid close attention to them, Captain Smith would have realized that the Titanic was heading into an immense swath of ice, nearly eighty miles wide. At a minimum, this may have prompted Captain Smith to reduce the speed of the Titanic, which could have averted the collision in the first place.

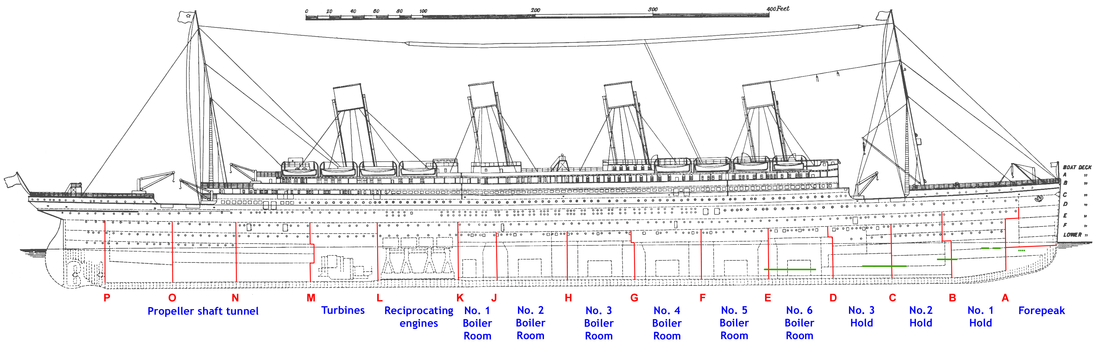

Another relatively new technology that was incorporated into the Titanic was a system of 16 watertight compartments formed by 15 transverse bulkheads (shown in red below). The number and placement of the bulkheads were selected to allow the Titanic to stay afloat if any two adjoining compartments were flooded, or a total of three, or under certain conditions, a total of four compartments were flooded. The bulkheads were provided with heavy cast iron doors that, under normal conditions, were left open, but could be closed locally, remotely or automatically. In the event of an accident, an electric switch located on the bridge could be activated to close all of the doors at the same time. In addition, each compartment had a float-activated switch that would automatically close the door of the compartment if water in the compartment exceeded six inches. The time required for the doors to close was between 25 and 30 seconds and a warning bell sounded when a door was closing.

One of the weaknesses of the system of water tight compartments was that the bulkheads did not extend very high into the ship. The first two bulkheads (located toward the bow) and the last five bulkheads (located toward the stern) extended up to the D deck, while the remaining seven bulkheads only extended up to the E deck, which was only fifteen feet above the waterline.

When the Titanic struck the iceberg, William Murdoch, who was in command of the bridge on the Titanic quickly activated the switch to close the watertight doors, which worked as designed. However, the impact had ruptured the first four compartments, causing them to fill with water. This pulled the bow of the ship downward, causing water from the fourth compartment to spill over the bulkhead into the fifth compartment and so on, in a cascading manner, until the Titanic completely sank.

In the British inquiry into the sinking of the Titanic, it was postulated that the closing of the watertight doors may have actually hastened the sinking of the Titanic; the reasoning being that if the doors had been left open, water would have flowed through them to the after part of the ship instead of building up in the forward part of the ship, weighing down the bow and causing the water to cascade over the bulkheads.

When the Titanic struck the iceberg, William Murdoch, who was in command of the bridge on the Titanic quickly activated the switch to close the watertight doors, which worked as designed. However, the impact had ruptured the first four compartments, causing them to fill with water. This pulled the bow of the ship downward, causing water from the fourth compartment to spill over the bulkhead into the fifth compartment and so on, in a cascading manner, until the Titanic completely sank.

In the British inquiry into the sinking of the Titanic, it was postulated that the closing of the watertight doors may have actually hastened the sinking of the Titanic; the reasoning being that if the doors had been left open, water would have flowed through them to the after part of the ship instead of building up in the forward part of the ship, weighing down the bow and causing the water to cascade over the bulkheads.

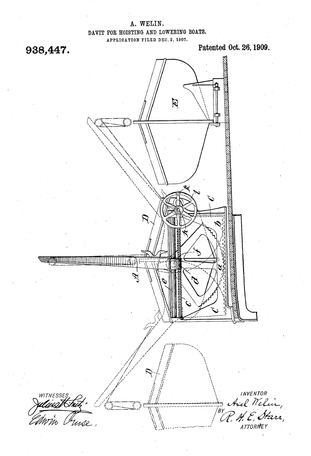

U.S. Patent No.: 938,447

U.S. Patent No.: 938,447

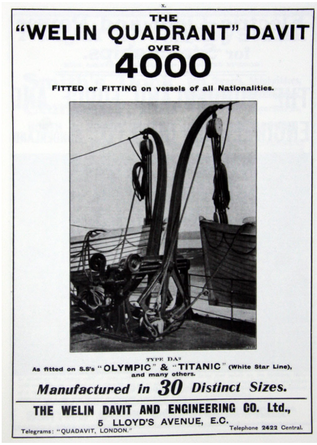

Another innovation employed on the Titanic that could have saved many lives was a new lifeboat davit, which, if fully utilized, could have ensured that a sufficient number of lifeboats were available to rescue all of the passengers of the Titanic. As it was, the Titanic only had enough lifeboats for 1,178 people, which was a primary cause of the large loss of life.

The new lifeboat davit employed on the Titanic was a double-acting quadrant davit that was manufactured by the Welin Davit and Engineering Company of London. The Welin quadrant davit was covered by U.S. Patent No. 938,447, which issued on October 26, 1909. The davit had two long, curved arms, each of which was joined to a bottom quadrant having a series of teeth. Two bottom racks were provided for the davit arms, respectively, each of which was engaged with the quadrant teeth of one of the davit arms. Worms rotatable by wheels were connected by nuts to the davit arms, respectively. The worms, actuated by the wheels, were operable to pivot the arms of the davit both inwardly and outwardly, which allowed the davit to access and deploy lifeboats from two pairs of stacked lifeboats, arranged side-by-side. In this manner, the davit could accommodate four lifeboats.

The Titanic was fitted with 16 sets of the Welin quadrant davits. As such, the Welin quadrant davits of the Titanic were capable of, and indeed were initially intended to, accommodate 64 lifeboats; more than enough to handle the ship’s maximum capacity of 3,600 people. However, it was determined that the presence of 64 lifeboats on the decks of the Titanic would be unsightly and block the views of the first-class passengers. Accordingly, the number of lifeboats carried by the davits was reduced to 16. And, as they say, the rest is history.

The new lifeboat davit employed on the Titanic was a double-acting quadrant davit that was manufactured by the Welin Davit and Engineering Company of London. The Welin quadrant davit was covered by U.S. Patent No. 938,447, which issued on October 26, 1909. The davit had two long, curved arms, each of which was joined to a bottom quadrant having a series of teeth. Two bottom racks were provided for the davit arms, respectively, each of which was engaged with the quadrant teeth of one of the davit arms. Worms rotatable by wheels were connected by nuts to the davit arms, respectively. The worms, actuated by the wheels, were operable to pivot the arms of the davit both inwardly and outwardly, which allowed the davit to access and deploy lifeboats from two pairs of stacked lifeboats, arranged side-by-side. In this manner, the davit could accommodate four lifeboats.

The Titanic was fitted with 16 sets of the Welin quadrant davits. As such, the Welin quadrant davits of the Titanic were capable of, and indeed were initially intended to, accommodate 64 lifeboats; more than enough to handle the ship’s maximum capacity of 3,600 people. However, it was determined that the presence of 64 lifeboats on the decks of the Titanic would be unsightly and block the views of the first-class passengers. Accordingly, the number of lifeboats carried by the davits was reduced to 16. And, as they say, the rest is history.