Berliner Microphone, March 4, 1877

Berliner Microphone, March 4, 1877

On March 4 of the year 1877, Emile Berliner displayed a crude device he had constructed to a group of friends who had stopped by his Washington D.C. residence on the way to the presidential inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes. Berliner had constructed the device from a membrane of a toy drum, a common sewing needle, a guitar string and a steel dress button. The device Berliner had constructed was a microphone for the newly invented telephone. Berliner's microphone was a marked improvement over the transmitter developed by Alexander Graham Bell and helped make practical use of the telephone possible.

Berliner filed a caveat (similar to the modern provisional patent application) on April 14, 1877 and then a regular patent application on June 4, 1877 for his microphone. The microphone described in Berliner's caveat and patent application was essentially a metal plate that vibrated against a metal ball. It was what is now referred to as a loose-contact type of microphone.

Two weeks after Berliner filed the caveat for his microphone, Thomas Edison filed a patent application for a loose-contact type of microphone in which a metal diaphragm vibrated against a large flat disk covered with graphite. On March 16, 1878, an interference was declared by the Commissioner of Patents among the Berliner and Edison patent applications and several others. The interference would determine who was the first inventor of the loose-contact type of microphone.

The American Bell Telephone Company, through its attorney Anthony Pollok, investigated the interference to determine if any of the involved patent applications should be purchased by the American Bell Telephone Company. From information he obtained from a source within the Patent Office, Pollok advised the American Bell Telephone Company that Berliner's patent application should be purchased. Since the interference and the pending patent applications were supposed to be kept secret, the source within the Patent Office was clearly acting improperly.

In September of 1878, the American Bell Telephone Company entered into an arrangement with Berliner in which Berliner became an employee of the American Bell Telephone Company and assigned his rights in his June 4, 1877 patent application to them. A year later, the American Bell Telephone Company obtained ownership of Edison's patent application for his loose-contact type of microphone as a result of the settlement of a lawsuit. Thus, in 1879, the American Bell Telephone Company became the owner of the two main patent applications that were involved in the patent interference being conducted in the Patent Office.

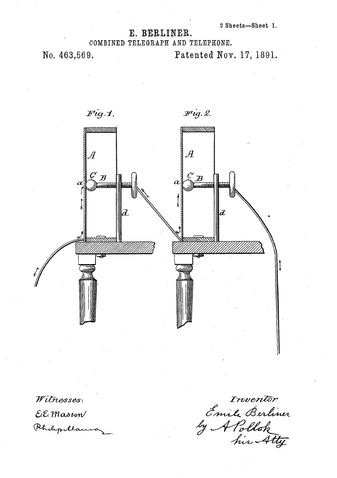

Suspiciously, the interference between the Berliner and Edison patent applications dragged on until late 1891, which resulted in the Berliner patent application issuing as U.S. Patent No. 463,569 on November 17, 1891 (more than fourteen years after its filing date). The issuance of the Berliner patent was a little more than a year before Bell's original patent for the telephone was set to expire. As such, the Berliner patent would effectively extend the American Bell Telephone Company's monopoly on the telephone for an additional 16 years, until November 1908. This coincidence did not go unnoticed by the U.S. government.

On February 1, 1893, the U.S. Attorney General filed suit in the Circuit Court of the District of Massachusetts against the American Bell Telephone Company to annul the Berliner patent based on fraud. The Circuit Court voided the patent on January 3, 1895, stating: "Their acts were so gross as to forbid any inference except that they dishonestly delayed the issue of the patent". The government's victory, however, was short lived. On May 18, 1895, the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit reversed the Circuit Court's decision and directed dismissal of all proceedings. The Supreme Court affirmed the Court of Appeals' decision on May 10, 1897, more than twenty years after Berliner filed his original caveat.

Ironically, Berliner's patent probably never should have issued in the first place (or at least with the claim scope it had). Berliner's microphone was substantially the same as a microphone built and publicly demonstrated by the German, Philipp Reis, in 1864, as well as by a microphone developed by the American, James W. McDonough, who filed a patent application for his invention on April 10, 1876. Both Reis and McDonough incorrectly described their microphones as making and breaking electrical connections in response to sound waves. The scientific community, as well as the U.S. Patent Office, correctly noted that speech could not be transmitted by making and breaking electrical connections. As such, the Reis and McDonough microphones were dismissed by the scientific community, and McDonough's patent application was rejected by the U.S. Patent Office, because they were based on a "false theory", even though both microphones were demonstrated to have worked. And this is where the story gets interesting.

Berliner's patent application, as originally filed, contained passages describing the Berliner microphone as making and breaking electrical connections, just like Reis and McDonough. However, after obtaining ownership of the Berliner patent application, the American Bell Telephone Company filed amendments to the Berliner patent application deleting these passages.

Berliner filed a caveat (similar to the modern provisional patent application) on April 14, 1877 and then a regular patent application on June 4, 1877 for his microphone. The microphone described in Berliner's caveat and patent application was essentially a metal plate that vibrated against a metal ball. It was what is now referred to as a loose-contact type of microphone.

Two weeks after Berliner filed the caveat for his microphone, Thomas Edison filed a patent application for a loose-contact type of microphone in which a metal diaphragm vibrated against a large flat disk covered with graphite. On March 16, 1878, an interference was declared by the Commissioner of Patents among the Berliner and Edison patent applications and several others. The interference would determine who was the first inventor of the loose-contact type of microphone.

The American Bell Telephone Company, through its attorney Anthony Pollok, investigated the interference to determine if any of the involved patent applications should be purchased by the American Bell Telephone Company. From information he obtained from a source within the Patent Office, Pollok advised the American Bell Telephone Company that Berliner's patent application should be purchased. Since the interference and the pending patent applications were supposed to be kept secret, the source within the Patent Office was clearly acting improperly.

In September of 1878, the American Bell Telephone Company entered into an arrangement with Berliner in which Berliner became an employee of the American Bell Telephone Company and assigned his rights in his June 4, 1877 patent application to them. A year later, the American Bell Telephone Company obtained ownership of Edison's patent application for his loose-contact type of microphone as a result of the settlement of a lawsuit. Thus, in 1879, the American Bell Telephone Company became the owner of the two main patent applications that were involved in the patent interference being conducted in the Patent Office.

Suspiciously, the interference between the Berliner and Edison patent applications dragged on until late 1891, which resulted in the Berliner patent application issuing as U.S. Patent No. 463,569 on November 17, 1891 (more than fourteen years after its filing date). The issuance of the Berliner patent was a little more than a year before Bell's original patent for the telephone was set to expire. As such, the Berliner patent would effectively extend the American Bell Telephone Company's monopoly on the telephone for an additional 16 years, until November 1908. This coincidence did not go unnoticed by the U.S. government.

On February 1, 1893, the U.S. Attorney General filed suit in the Circuit Court of the District of Massachusetts against the American Bell Telephone Company to annul the Berliner patent based on fraud. The Circuit Court voided the patent on January 3, 1895, stating: "Their acts were so gross as to forbid any inference except that they dishonestly delayed the issue of the patent". The government's victory, however, was short lived. On May 18, 1895, the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit reversed the Circuit Court's decision and directed dismissal of all proceedings. The Supreme Court affirmed the Court of Appeals' decision on May 10, 1897, more than twenty years after Berliner filed his original caveat.

Ironically, Berliner's patent probably never should have issued in the first place (or at least with the claim scope it had). Berliner's microphone was substantially the same as a microphone built and publicly demonstrated by the German, Philipp Reis, in 1864, as well as by a microphone developed by the American, James W. McDonough, who filed a patent application for his invention on April 10, 1876. Both Reis and McDonough incorrectly described their microphones as making and breaking electrical connections in response to sound waves. The scientific community, as well as the U.S. Patent Office, correctly noted that speech could not be transmitted by making and breaking electrical connections. As such, the Reis and McDonough microphones were dismissed by the scientific community, and McDonough's patent application was rejected by the U.S. Patent Office, because they were based on a "false theory", even though both microphones were demonstrated to have worked. And this is where the story gets interesting.

Berliner's patent application, as originally filed, contained passages describing the Berliner microphone as making and breaking electrical connections, just like Reis and McDonough. However, after obtaining ownership of the Berliner patent application, the American Bell Telephone Company filed amendments to the Berliner patent application deleting these passages.

Proudly powered by Weebly