The Most Beautiful Woman in the World

and the Bad Boy of Music

March 2018

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr

At the height of her career in the 1940s, Austrian-born actress Hedy Lamarr (whose real name was Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler) was known as the “most beautiful woman in the world”, a moniker that was not undeserved. She was so beautiful, movie audiences would gasp when she first appeared on screen. What is not as well known is that Hedy was an avid inventor. Indeed, one of her inventions is widely used today and earned her a place in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Read on to learn more. It’s a Patently Interesting story!

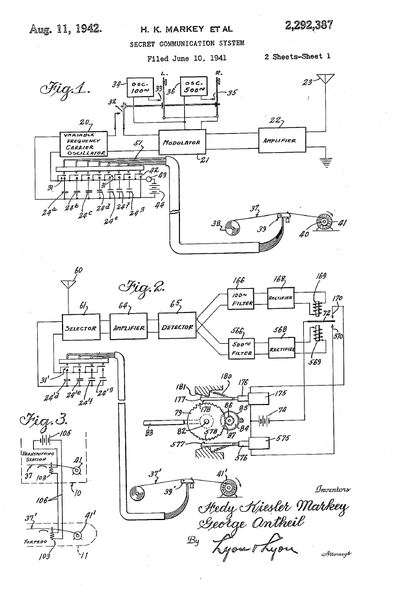

Instead of attending lavish Hollywood parties, Hedy would stay at home and invent. She so enjoyed inventing that she set up an inventor’s retreat in the drawing room of her home, replete with drawing boards and drafting tools. Hedy never made any money from her inventions and most of them never advanced very far; however, one invention earned her a place in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. This invention (for which she was granted U.S. Patent No. 2,292,387) was for a form of wireless communication that Hedy called “hopping of frequencies”. Today, this form of communication is known as “frequency hopping spread spectrum communication” (FHSS), and is one of two two basic modulation techniques used in spread spectrum signal transmission. The ubiquitous Bluetooth is a form of FHSS.

Hedy came up with the idea of frequency hopping in the course of developing a broader invention that she hoped would help the U.S. war effort (in World War II): a wireless torpedo. Hedy believed that a wireless torpedo could be used to combat the German submarines that were menacing the Atlantic, sinking Allied shipping. During her development of the torpedo, Hedy quickly realized that the radio signals controlling the torpedo could be jammed and determined that frequency hopping was the solution. In its most simple form, a radio receiver in the torpedo and a radio transmitter in the launch ship (or an airplane) would be synchronized to change their tuning from time to time so as to hop together from frequency to frequency. Since the control signal was not limited to a single frequency, it effectively could not be jammed.

Instead of attending lavish Hollywood parties, Hedy would stay at home and invent. She so enjoyed inventing that she set up an inventor’s retreat in the drawing room of her home, replete with drawing boards and drafting tools. Hedy never made any money from her inventions and most of them never advanced very far; however, one invention earned her a place in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. This invention (for which she was granted U.S. Patent No. 2,292,387) was for a form of wireless communication that Hedy called “hopping of frequencies”. Today, this form of communication is known as “frequency hopping spread spectrum communication” (FHSS), and is one of two two basic modulation techniques used in spread spectrum signal transmission. The ubiquitous Bluetooth is a form of FHSS.

Hedy came up with the idea of frequency hopping in the course of developing a broader invention that she hoped would help the U.S. war effort (in World War II): a wireless torpedo. Hedy believed that a wireless torpedo could be used to combat the German submarines that were menacing the Atlantic, sinking Allied shipping. During her development of the torpedo, Hedy quickly realized that the radio signals controlling the torpedo could be jammed and determined that frequency hopping was the solution. In its most simple form, a radio receiver in the torpedo and a radio transmitter in the launch ship (or an airplane) would be synchronized to change their tuning from time to time so as to hop together from frequency to frequency. Since the control signal was not limited to a single frequency, it effectively could not be jammed.

George Antheil

George Antheil

While Hedy came up with the basic idea of using frequency hopping in wireless communication, it was her co-inventor, George Antheil, who created the system that carried out the invention, i.e., reduced it to practice. George had no formal technical education, but was technically skilled, amongst his many other talents. Indeed, George was well versed in a number of disparate fields. He was a talented composer/musician, an engaging writer and well-read in the field of endocrinology (such as it existed at the time). While it was George’s music that gave him fame (or infamy), it was his knowledge of endocrinology, that brought him together with Hedy.

George styled himself the “bad boy of music” because of his experiences as an advant garde composer and musician in Europe during the 1920s. His compositions were so radical, particularly his Ballet mécanique, that they allegedly caused riots when they were publicly performed. George claimed that he carried a pistol to his performances and if the crowd got too rambunctious, he would pull the pistol out and place it on top of his piano. At the height of his fame (or notoriety), George moved in the same social circles as some of the most prominent literary, musical and artistic figures of the time, such as James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Ernest Hemingway, Eric Satie, and Igor Stravinsky. However, George’s fame was short-lived and he soon slipped into the mundane, returning to the U.S. in 1933 and thereafter struggling to make a living by writing articles for Esquire magazine and composing movie scores for lesser-known films.

George’s Esquire articles were essentially pick-up guides based on his study of endocrinology, particularly the effects of glandular activity on (female) physiology and behavior. In 1937, George followed up his Esquire articles with a book entitled “Every Man His Own Detective: A Study of Glandular Criminology” in which George detailed how different types of crimes could be tied to disorders in particular glands and how these disorders caused specific physiological and behavioral characteristics, which could be used to identify suspects.

It was George’s writings on endocrinology that caught Hedy’s attention. Louis B. Mayer (the head of MGM) had suggested to Hedy that she try to increase her bust size. Hedy thought that with George’s knowledge of glands, George could help her do so. Accordingly, Hedy arranged to meet George through mutual friends, the costume designer, (Gilbert) Adrian, and his wife Janet Gaynor. Adrian was the head costume designer for MGM and was well known for his fashions. He designed the costumes for the Wizard of Oz, including Dorothy’s famous ruby slippers.

George and Hedy met at the Adrians’ house in August 1940 to discuss increasing the size of Hedy’s bosom. They met again the next day to continue their delicate discussions, but their conversation soon turned to the war and how Hedy had made several weapons-related inventions. Thereafter, George and Hedy began working together on Hedy’s idea of a wireless torpedo. Relying on his experience with synchronizing player pianos for his Ballet mécanique, George developed a communication system for the wireless torpedo that used identically-punched ribbons (similar to player piano rolls) in the radio transmitter and receiver, respectively, to simultaneously change their frequencies. Once George completed the communication system, Hedy and George filed a patent application for the system. A little over a year later, on August 11, 1942, the application issued as U.S. Patent No.: 2,292,387.

While Hedy and George were successful in obtaining a patent for their communication system, they were less fortunate in convincing the U.S. Navy to use their invention. The Navy declined to pursue their invention because it was preoccupied with simply getting its torpedoes to work on a fundamental level; it being estimated that 60% of the Navy’s torpedoes were duds at the time. As a result of the Navy’s rejection, George and Hedy’s frequency hopping communication system was not utilized for the next twenty years. It was not until the early 1960s that a similar communication system was adopted by the U.S. Navy, and it was not until the 1980s that FHSS systems were commercially used. As with many other inventors, Hedy and George were unfortunately way ahead of their time.

George styled himself the “bad boy of music” because of his experiences as an advant garde composer and musician in Europe during the 1920s. His compositions were so radical, particularly his Ballet mécanique, that they allegedly caused riots when they were publicly performed. George claimed that he carried a pistol to his performances and if the crowd got too rambunctious, he would pull the pistol out and place it on top of his piano. At the height of his fame (or notoriety), George moved in the same social circles as some of the most prominent literary, musical and artistic figures of the time, such as James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Ernest Hemingway, Eric Satie, and Igor Stravinsky. However, George’s fame was short-lived and he soon slipped into the mundane, returning to the U.S. in 1933 and thereafter struggling to make a living by writing articles for Esquire magazine and composing movie scores for lesser-known films.

George’s Esquire articles were essentially pick-up guides based on his study of endocrinology, particularly the effects of glandular activity on (female) physiology and behavior. In 1937, George followed up his Esquire articles with a book entitled “Every Man His Own Detective: A Study of Glandular Criminology” in which George detailed how different types of crimes could be tied to disorders in particular glands and how these disorders caused specific physiological and behavioral characteristics, which could be used to identify suspects.

It was George’s writings on endocrinology that caught Hedy’s attention. Louis B. Mayer (the head of MGM) had suggested to Hedy that she try to increase her bust size. Hedy thought that with George’s knowledge of glands, George could help her do so. Accordingly, Hedy arranged to meet George through mutual friends, the costume designer, (Gilbert) Adrian, and his wife Janet Gaynor. Adrian was the head costume designer for MGM and was well known for his fashions. He designed the costumes for the Wizard of Oz, including Dorothy’s famous ruby slippers.

George and Hedy met at the Adrians’ house in August 1940 to discuss increasing the size of Hedy’s bosom. They met again the next day to continue their delicate discussions, but their conversation soon turned to the war and how Hedy had made several weapons-related inventions. Thereafter, George and Hedy began working together on Hedy’s idea of a wireless torpedo. Relying on his experience with synchronizing player pianos for his Ballet mécanique, George developed a communication system for the wireless torpedo that used identically-punched ribbons (similar to player piano rolls) in the radio transmitter and receiver, respectively, to simultaneously change their frequencies. Once George completed the communication system, Hedy and George filed a patent application for the system. A little over a year later, on August 11, 1942, the application issued as U.S. Patent No.: 2,292,387.

While Hedy and George were successful in obtaining a patent for their communication system, they were less fortunate in convincing the U.S. Navy to use their invention. The Navy declined to pursue their invention because it was preoccupied with simply getting its torpedoes to work on a fundamental level; it being estimated that 60% of the Navy’s torpedoes were duds at the time. As a result of the Navy’s rejection, George and Hedy’s frequency hopping communication system was not utilized for the next twenty years. It was not until the early 1960s that a similar communication system was adopted by the U.S. Navy, and it was not until the 1980s that FHSS systems were commercially used. As with many other inventors, Hedy and George were unfortunately way ahead of their time.

Proudly powered by Weebly