A young boy falls into a drainage canal filled with garbage. Not knowing how to swim, the boy instinctively rolls over onto his back and kicks his feet, making his way to safety. It is an inauspicious start to an illustrious swimming career that includes numerous national and world records and an Olympic gold medal. The swimmer's success is due, in part, to innovations he makes in his swim stroke and his turn at the wall. This spirit of innovation helps him later become a successful inventor and businessman. The swimmer's name is Adolph Kiefer and his life is a Patently Interesting story!

Adolph Gustav Kiefer was born on June 27, 1918 in Chicago, Illinois to Otto and Emma Kiefer, who were German immigrants. After Adolph's tumble into the drainage canal, Otto encouraged Adolph to participate in competitive swimming. Adolph's initial swimming experience in the canal, coupled with a dislike of getting water up his nose, made backstroke a natural choice for him to pursue. And pursue it he did. He quickly became proficient in the stroke and developed his own variation on it, which would become known as the Kiefer style. In the Kiefer style backstroke, the arms were alternately recovered, elbows straight, with a low lateral swing over the water. After recovery, each arm entered the water, wide of the shoulder, and was pulled just below the surface, while being kept straight. This shallow pull was in contrast to the then-customary deep pull.

As a sophomore in high school, 15-year-old Adolph won the 100-yard backstroke at the 1934 Illinois State High School championship, with a time of 1:03.8. Later that year, Adolph's participated in his first major swimming competition at the AAU nationals held at the Chicago World's Fair. Barely 16 years old, Adolph led the 100-meter backstroke race until the turn, which he badly fumbled, allowing two other swimmers to overtake him. Adolph ended up finishing third, behind Albert Vande Weghe and Robert Daniel Zehr, who were also teen swimming phenoms. Adolph would not lose another race for the next nine years.

In 1935, Adolph burst onto the world stage. He broke the world's record in the 100-yard backstroke at the 1935 Illinois State High School championship. In doing so, he became the first person to break the one-minute mark, clocking in at 59.8 seconds. Soon after, Adolph broke world records in the 150-yard backstroke, the 200-yard backstroke, the 100-meter backstroke, the 200-meter backstroke and the 400-meter backstroke. In December of 1935, Adolph again broke the world record for the 100-yard backstroke at a Chicago high school meet, with a time of 57.6 seconds.

During 1935, Adolph worked on another innovation: the backstroke flip-turn. In this maneuver, Adolph would approach a pool wall on his back and when his hand touched the wall, he would do a backward half somersault, then twist his body as he pushed off the wall to regain his position on his back. Adolph first used the backstroke flip turn in competition in 1935 and perfected it in 1936. In April of 1936, Adolph's flip-turn caught people's attention when he used it to shatter the world record in the 150-yard backstroke by more than four seconds. Later that summer, Adolph's flip turn was showcased in the 100-meter backstroke at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany. From the beginning of the race, the crowd knew that Adolph would win and were rather subdued. However, as soon as Adolph flawlessly executed his flip-turn, the crowd burst into cheers. The turn increased Adolph's lead over his two closest rivals and allowed him to cruise to an easy victory and an Olympic record of 1:05.9. Fellow American, Al Vande Weghe, who had beaten Adolf two years earlier, placed second with a time of 1:07.7.

Ironically, it was Al Vande Weghe who had first invented the backstroke flip-turn back in late 1933. He first used it in competition at the AAU nationals meet in Columbus, Ohio in April of 1934, setting a world record in the 150-yard backstroke. While Vande Weghe invented the backstroke flip-turn, it was Adolph who perfected it and became closely associated with it, so much so that its invention has been erroneously attributed to Adolph.

After the 1936 Olympics, Adolph traveled the world, giving swim demonstrations and taking part in numerous races. He then attended the University of Texas, Northwestern University and Columbia University before entering the Navy in 1943 as an athletics specialist. Adolph was quickly promoted to become the officer in charge of swimming instruction for the entire Navy. In this role, Adolph completely revamped the Navy's swim instruction program and even developed a new stroke, the Victory backstroke, which was a double arm backstroke that permitted novice swimmers to swim longer with less effort. The Victory backstroke was credited with saving the lives of many stranded U.S. sailors during World War II; an achievement that Adolph was most proud of.

During 1935, Adolph worked on another innovation: the backstroke flip-turn. In this maneuver, Adolph would approach a pool wall on his back and when his hand touched the wall, he would do a backward half somersault, then twist his body as he pushed off the wall to regain his position on his back. Adolph first used the backstroke flip turn in competition in 1935 and perfected it in 1936. In April of 1936, Adolph's flip-turn caught people's attention when he used it to shatter the world record in the 150-yard backstroke by more than four seconds. Later that summer, Adolph's flip turn was showcased in the 100-meter backstroke at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany. From the beginning of the race, the crowd knew that Adolph would win and were rather subdued. However, as soon as Adolph flawlessly executed his flip-turn, the crowd burst into cheers. The turn increased Adolph's lead over his two closest rivals and allowed him to cruise to an easy victory and an Olympic record of 1:05.9. Fellow American, Al Vande Weghe, who had beaten Adolf two years earlier, placed second with a time of 1:07.7.

Ironically, it was Al Vande Weghe who had first invented the backstroke flip-turn back in late 1933. He first used it in competition at the AAU nationals meet in Columbus, Ohio in April of 1934, setting a world record in the 150-yard backstroke. While Vande Weghe invented the backstroke flip-turn, it was Adolph who perfected it and became closely associated with it, so much so that its invention has been erroneously attributed to Adolph.

After the 1936 Olympics, Adolph traveled the world, giving swim demonstrations and taking part in numerous races. He then attended the University of Texas, Northwestern University and Columbia University before entering the Navy in 1943 as an athletics specialist. Adolph was quickly promoted to become the officer in charge of swimming instruction for the entire Navy. In this role, Adolph completely revamped the Navy's swim instruction program and even developed a new stroke, the Victory backstroke, which was a double arm backstroke that permitted novice swimmers to swim longer with less effort. The Victory backstroke was credited with saving the lives of many stranded U.S. sailors during World War II; an achievement that Adolph was most proud of.

Adolph Kiefer

Adolph Kiefer

While he was in college and in the Navy, Adolph continued to swim and set world and national records. In 1943, he suffered his first loss in more than nine years, to Harry Holiday, a sophomore at the University of Michigan. The loss occurred in the 150-yard backstroke and, ironically, was caused by Adolph missing his flip-turn going into the final lap, similar to what happened back in 1934. Adolph, however, rebounded the next year to defeat Holiday and continue his backstroke dominance. Two years later, in 1946, Adolph retired from competitive swimming, leaving behind a prodigious legacy and numerous records. During his career, Adolph held the world and American records in every backstroke event. He also held the American record in the three-stroke individual medley (150 meters). His high school record of 58.5 seconds for the 100-yard backstroke, set in 1936, would not be broken until 1960.

Although Adolph retired from competition, he did not retire from swimming. In 1947, Adolph started developing and selling swimming-based products through his newly formed company, Adolph Kiefer and Associates. In this new venture, Adolph employed the same inventiveness he had used as a competitive swimmer and Navy swim instructor. In 1948, he developed the first nylon racing trunk (swimsuit) for men, which was supplied to the U.S. Olympic Swim Team in both the 1948 and 1952 Olympics. Later, he developed the first commercial plastic kickboard and introduced swim goggles with soft rubber gaskets.

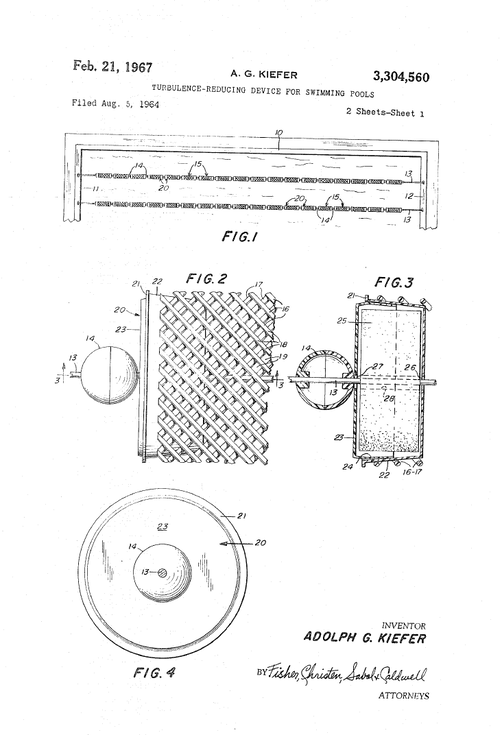

Adolph's most successful invention was a lane line for reducing turbulence in a pool. Prior lane lines were focused mainly on delineating separate swimming lanes and perhaps confining waves within a lane. Adolph's lane line was the first to focus on breaking-up waves. The lane line included a series of spaced-apart, partially buoyant cylinders, each having a sidewall formed of plastic strips arranged in a latticework so as to form an array of perforations. Adolph filed a patent application for the lane line in 1964 and received two patents for it, one of which issued in February of 1967 (U.S. Patent No.: 3,304,560) and one of which issued in March of 1970 (U.S. Patent No.: 3,498,246). The lane line was sold throughout the world under the trademark "Non-Turb" and was used in the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. (N1)

Swimming was important to Adolph throughout his entire life. Well into advanced age and even with declining health, Adolph continued to swim. Indeed, Adolph attributed his longevity to swimming, asserting that it kept him alive, which it did, for almost 100 years. Adolph passed away on May 5, 2017, less than two months away from his 99th birthday, leaving behind a rich legacy. Perhaps no other person has combined athletic talent with innovation and business acumen like Adolph Kiefer.

Notes:

N1: Adolph formed a venture with McNeil Corp. of Akron, Ohio to market and sell the Non-Turb lane lines, as well as develop new wave quelling technology. The Kiefer-McNeil venture later developed a new lane line comprising rotatable perforated discs with vanes that was covered by U.S. Patent No.: 3,755,829 to Walklet. The new lane line was sold under the "Competitor" trademark and was used in the 1976 Olympics. A modification of this lane line was made by Thomas Rademacher and patented by Keifer-McNeil in 1986 (U.S. Patent No. 4,616,369). Like Adolph, Thomas Rademacher was a gold medal Olympian.

Adolph's most successful invention was a lane line for reducing turbulence in a pool. Prior lane lines were focused mainly on delineating separate swimming lanes and perhaps confining waves within a lane. Adolph's lane line was the first to focus on breaking-up waves. The lane line included a series of spaced-apart, partially buoyant cylinders, each having a sidewall formed of plastic strips arranged in a latticework so as to form an array of perforations. Adolph filed a patent application for the lane line in 1964 and received two patents for it, one of which issued in February of 1967 (U.S. Patent No.: 3,304,560) and one of which issued in March of 1970 (U.S. Patent No.: 3,498,246). The lane line was sold throughout the world under the trademark "Non-Turb" and was used in the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. (N1)

Swimming was important to Adolph throughout his entire life. Well into advanced age and even with declining health, Adolph continued to swim. Indeed, Adolph attributed his longevity to swimming, asserting that it kept him alive, which it did, for almost 100 years. Adolph passed away on May 5, 2017, less than two months away from his 99th birthday, leaving behind a rich legacy. Perhaps no other person has combined athletic talent with innovation and business acumen like Adolph Kiefer.

Notes:

N1: Adolph formed a venture with McNeil Corp. of Akron, Ohio to market and sell the Non-Turb lane lines, as well as develop new wave quelling technology. The Kiefer-McNeil venture later developed a new lane line comprising rotatable perforated discs with vanes that was covered by U.S. Patent No.: 3,755,829 to Walklet. The new lane line was sold under the "Competitor" trademark and was used in the 1976 Olympics. A modification of this lane line was made by Thomas Rademacher and patented by Keifer-McNeil in 1986 (U.S. Patent No. 4,616,369). Like Adolph, Thomas Rademacher was a gold medal Olympian.