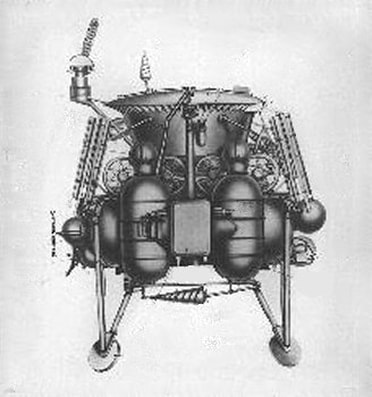

Schematic of the Luna 17

Schematic of the Luna 17

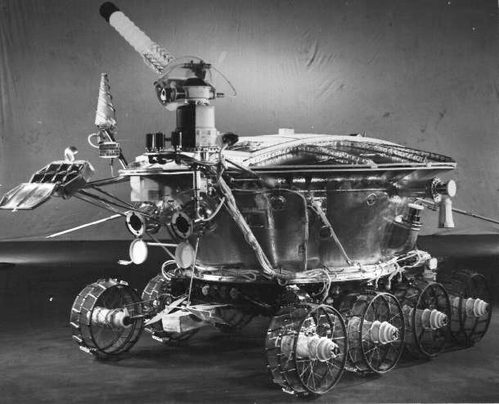

On November 17 of the year 1970, the Luna 17 spacecraft gently landed on the moon, carrying the Lunokhod 1 (Moonwalker 1) lunar rover. Two ramps emerged from the Luna 17 and the Lunokhod 1 slowly drove down one of the ramps and onto the surface of the moon. Over the next 11 months, the Lunokhod 1 would travel over 10.5 km across the lunar surface, making it the first robotic rover to explore a stellar object. The Lunokhod 1 was originally designed to scout landing sites for future manned missions to the moon and to act as a radio beacon for these missions. The Lunokhod 1 was built and transported to the moon by the Soviet Union, so, needless to say, these manned missions never materialized.

The chief designer of the Lunokhod 1 was the Soviet scientist, Aleksandr Kemurdzhian, who was of Armenian heritage. Between 1963 and 1973, Kemurdzhian headed the Soviet Union's design of self-propelled lunar rovers within the Science and Research Institute VNII-100, later called the All-Russia Research and Development Institute of Transport Machine-Building ("VNIITransmash" for short). Kemurdzhian was a prolific researcher and inventor and later helped design the STR-1 robot, which was used to clear radioactive debris from the crippled Chernobyl nuclear power plant. While overseeing the operation of the STR-1 at Chernobyl, Kemurdzhian was exposed to so much radiation he had to be hospitalized.

Kemurdzhian and his team provided the Lunokhod 1 with a robust design, being about 4.5 feet high, 7 feet wide and weighing over 1,667 pounds. The Lunokhod 1 had a tub-shaped body supported on eight wire-mesh wheels, which were independently driven. A large convex lid was attached to the body by hinges so as to permit the lid to be pivoted to an open position, thereby exposing a solar cell array mounted to the underside of the lid. During the lunar day, the lid was opened to permit the solar cell array to charge the batteries that powered the Lunokhod 1. During the lunar night, the lid was closed and a polonium-210 radioisotope heater was used to keep the internal components at a suitable operating temperature, well above the frigid outside temperature of minus 150 degrees Celsius (minus 238 Fahrenheit). Since the lunar day and the lunar night each last about two Earth weeks, the lid would be kept in its open or closed position for two weeks at a time.

The Lunokhod 1 was provided with two antennas, one that was cone-shaped and one that was helical and highly directional. The antennas permitted the Lunokhod 1 to be controlled remotely by a five-man team of "drivers" at the Deep Space Center, outside of Moscow, who had to cope with a 5-second communications delay. The Lunokhod 1 was also equipped with two television cameras, four high-resolution photometers, radiation detectors, an X-ray telescope and special extendable devices to test the lunar soil for soil density and mechanical properties. During its operational life span of 322 Earth days, the Lunokhod 1 analyzed the soil at a plurality of different locations and transmitted the results back to Earth, along with more than 20,000 TV images, and 206 high-resolution panoramas of the lunar landscape. Communication with the Lunokhod 1 was lost on October 4, 1971, exactly fourteen years after the Soviet Union's first satellite, Sputnik, reached Earth orbit.

The chief designer of the Lunokhod 1 was the Soviet scientist, Aleksandr Kemurdzhian, who was of Armenian heritage. Between 1963 and 1973, Kemurdzhian headed the Soviet Union's design of self-propelled lunar rovers within the Science and Research Institute VNII-100, later called the All-Russia Research and Development Institute of Transport Machine-Building ("VNIITransmash" for short). Kemurdzhian was a prolific researcher and inventor and later helped design the STR-1 robot, which was used to clear radioactive debris from the crippled Chernobyl nuclear power plant. While overseeing the operation of the STR-1 at Chernobyl, Kemurdzhian was exposed to so much radiation he had to be hospitalized.

Kemurdzhian and his team provided the Lunokhod 1 with a robust design, being about 4.5 feet high, 7 feet wide and weighing over 1,667 pounds. The Lunokhod 1 had a tub-shaped body supported on eight wire-mesh wheels, which were independently driven. A large convex lid was attached to the body by hinges so as to permit the lid to be pivoted to an open position, thereby exposing a solar cell array mounted to the underside of the lid. During the lunar day, the lid was opened to permit the solar cell array to charge the batteries that powered the Lunokhod 1. During the lunar night, the lid was closed and a polonium-210 radioisotope heater was used to keep the internal components at a suitable operating temperature, well above the frigid outside temperature of minus 150 degrees Celsius (minus 238 Fahrenheit). Since the lunar day and the lunar night each last about two Earth weeks, the lid would be kept in its open or closed position for two weeks at a time.

The Lunokhod 1 was provided with two antennas, one that was cone-shaped and one that was helical and highly directional. The antennas permitted the Lunokhod 1 to be controlled remotely by a five-man team of "drivers" at the Deep Space Center, outside of Moscow, who had to cope with a 5-second communications delay. The Lunokhod 1 was also equipped with two television cameras, four high-resolution photometers, radiation detectors, an X-ray telescope and special extendable devices to test the lunar soil for soil density and mechanical properties. During its operational life span of 322 Earth days, the Lunokhod 1 analyzed the soil at a plurality of different locations and transmitted the results back to Earth, along with more than 20,000 TV images, and 206 high-resolution panoramas of the lunar landscape. Communication with the Lunokhod 1 was lost on October 4, 1971, exactly fourteen years after the Soviet Union's first satellite, Sputnik, reached Earth orbit.