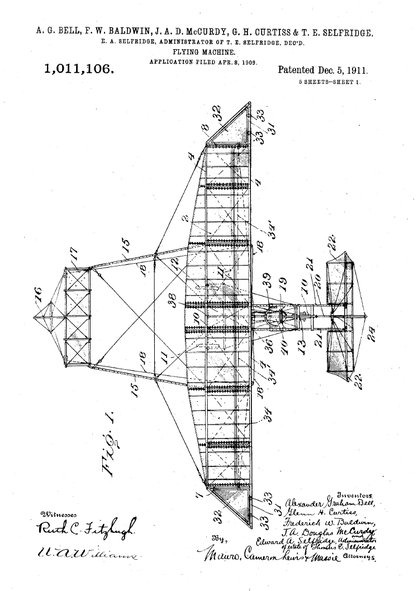

On April 8 of the year 1909, a patent application, entitled "Flying-Machine", was filed by a group of inventors known as the Aerial Experiment Association ("AEA"). The patent application would issue on December 5, 1911 as U.S. Patent No.: 1,011,106 and covered an airplane the AEA had earlier constructed known as the "June Bug". The members of the AEA included renowned inventors Dr. Alexander Graham Bell and Glenn Curtiss, as well as Frederick Baldwin, Douglas McCurdy and Edward Selfridge. On July 4, 1908, Glenn Curtiss flew the June Bug more than 1.6 km to win the Scientific American Trophy for the first official one-kilometer flight in North America. Earlier, in January of 1908, the Anglo-French aviator, Henri Farman had publicly flown more than 1 km at Issy-les-Moulineaux, just outside of Paris, France.

The AEA had formed on 30 September 1907, under the leadership of Dr. Bell, who had become interested in aeronautics in the late 1890s. The AEA produced a number of different aircraft in quick succession, with each member taking a turn being the principal designer of one of the aircraft.

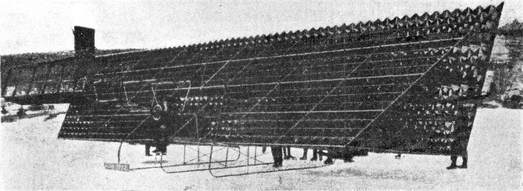

The Cygnet

The Cygnet

The first aircraft constructed by the AEA was an unconventional tetrahedral glider with floats called the "Cygnet", which was primarily designed by Dr. Bell. In December of 1907, the Cygnet was tested on Bras d'Or Lake in Nova Scotia by being pulled behind a lake steamer, with Selfridge at the controls. The test was successful in that the Cygnet attained a height of 168 feet and remained aloft for about 7 minutes. The test, however, was unsuccessful in that the Cygnet was completely destroyed. In their excitement, the team had forgotten to detach the cable connecting the Cygnet to the steamer such that when the steamer slowed, the Cygnet landed on the water and was subsequently dragged to pieces through the water.

The Red Wing

The Red Wing

The second aircraft constructed by the AEA was a powered biplane called the "Red Wing", which was primarily designed by Selfridge. The Red Wing was so named because its wings were made from the same red silk that had been used on the Cygnet. The Red Wing was mounted on sled runners, had a rudder on the tail and a single-plane elevator on the front. On March 12, 1908, with Baldwin at the controls, the Red Wingtook off from frozen Keuka Lake, near Hammondsport, New York and flew 319 feet at a height of around 20 feet before crash landing after its tail buckled. It was the first public demonstration of powered aircraft flight in North America.

The crash of the Red Wing highlighted one of the problems confronting early aircraft designers, which was controlling lateral (side-to-side) motion of aircraft. The Wright brothers had developed wing warping to control lateral movement, but the AEA wanted to avoid using this method for fear of infringing their patent. After observing the flight of birds, Dr. Bell arrived at a solution, which was to use ailerons (wing flaps). Unbeknownst to Dr. Bell, however, the use of ailerons had been discovered by others much earlier and had even been patented by the British scientist and inventor, Matthew Piers Watt Boulton way back in 1868. For that matter, wing warping was also known before the Wright brothers.

The AEA's next aircraft, the "White Wing", was equipped with ailerons, as well as a wheeled, tricycle undercarriage. The design and construction of the White Wing was overseen by Baldwin, who also piloted the aircraft on its maiden flight on May 18, 1908. After Baldwin, the White Wing was flown by Selfridge and then Glenn Curtiss, who had never flown before. And what a debut he had. Curtiss flew the White Wing farther than either Baldwin or Selfridge, achieving a distance of over 1,000 feet. The success of the White Wing soon came to an end, however, when it crashed during a landing by McCurdy and was damaged beyond repair.

The AEA's next aircraft, the "White Wing", was equipped with ailerons, as well as a wheeled, tricycle undercarriage. The design and construction of the White Wing was overseen by Baldwin, who also piloted the aircraft on its maiden flight on May 18, 1908. After Baldwin, the White Wing was flown by Selfridge and then Glenn Curtiss, who had never flown before. And what a debut he had. Curtiss flew the White Wing farther than either Baldwin or Selfridge, achieving a distance of over 1,000 feet. The success of the White Wing soon came to an end, however, when it crashed during a landing by McCurdy and was damaged beyond repair.

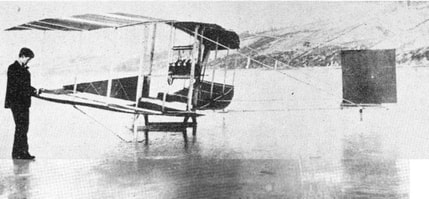

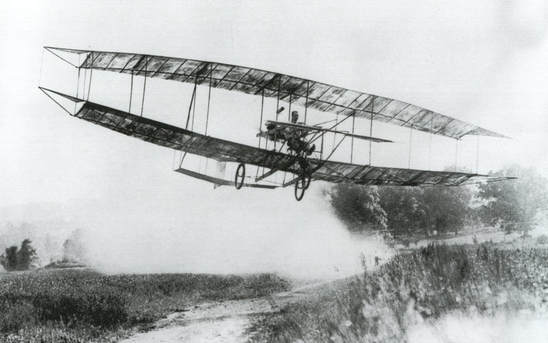

The June Bug

The June Bug

Next up for design duty was Curtiss, who oversaw the design and construction of the June Bug. As part of his effort, Curtiss constructed a wind tunnel for testing models of the new aircraft. With the help of the wind tunnel and the valuable information he learned from the prior AEA aircraft, Curtiss incorporated several new design elements into the June Bug. He increased the length of the June Bug's body to improve its horizontal front-to-rear stability and he modified its ailerons. He also listened to the suggestion of noted aviation pioneer, Octave Chanute, and coated the wings with a mixture of paraffin, gasoline, turpentine and yellow ochre to reduce wind resistance. With these important modifications, the June Bug was able to achieve its historic flight on July 4, 1908 at Hammondsport, New York to win the coveted Scientific American Trophy. Almost a year later, the application for the '106 patent was filed.

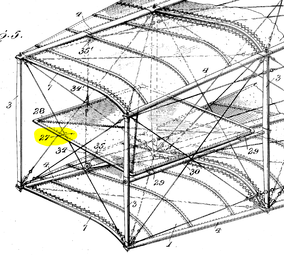

The claims of the '106 patent were directed to the ailerons of the June Bug. In the patent, the ailerons were referred to as "lateral balancing rudders". There were two lateral balancing rudders located between the upper and lower wings on opposite sides of the aircraft body, toward the outer tips of the wings, respectively. One of the lateral balancing rudders is shown in the drawing to the side and is designated with the reference numeral 27. Optionally, two additional lateral balancing rudders could be provided, one on each side of the body. These additional rudders were located at the outer tips of the upper wing, respectively. The lateral balancing rudders were pivotable about a horizontal axis and were connected by pulleys and wires to a harness worn by the pilot such that the pilot could control movement of the rudders simply by leaning to the left or right.

The '106 patent was the first patent on which Curtiss was named as an inventor. Before working with the AEA, Curtiss resented being called an inventor, stating that "An inventor, as people in country towns thought of him, was a wild-eyed, impractical person, with ideas that wouldn't work". Clearly, the success of the June Bug and the AEA changed Curtiss' way of thinking because Curtiss would go on to be an inventor on more than 84 patents, many of which were directed to pioneering inventions in the field of aviation. In 2003, Curtiss was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Postscript:

Noticeably absent from the foregoing discussion of aviation milestones is any mention of the Wright brothers and their Flyer. When the Wright brothers first flew the Flyer at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903, the event was a private affair. There were only five witnesses and no reporters. Indeed, the iconic photograph of the first flight was not published until May of 1908. Even then, it was not clear from thephotograph whether the Flyer was merely gliding or flying under its own power. In May of 1904, the Wright brothers invited the public and reporters to witness a demonstration of their Flyer at Huffman Prairie, near Dayton, Ohio. The demonstration was a failure and hugely embarrassing to the Wright brothers because, try as they might, they could not get the Flyer off the ground. The failure at Huffman Prairie coupled with the nature of the first flight at Kitty Hawk and the Wright's obsession with secrecy caused people to seriously question whether the Wright brothers had actually flown.

One of the more milder skeptics of the Wright brothers was the Scientific American magazine, who sponsored the Trophy that was eventually won by the June Bug. The Trophy was, in part, intended to urge the Wright brother to publicly demonstrate a successful flight of the Flyer. The Wright brothers would have none of it though. They were too busy preparing for aircraft trials with the Army and perhaps, more importantly, could not meet one of the requirements for winning the Trophy: the aircraft had to take off from level ground under its own power. In 1908, the Flyer could still only become airborne after being launched from a track through the use of a catapult. Indeed, it was not until the introduction of the Model B in 1910 that the Flyer was fitted with wheels and could take off on its own without assistance.

On August 8, 1908, Wilbur Wright finally flew the Flyer in public at the Hunaudieres race course, five miles south of Le Mans, France.

The '106 patent was the first patent on which Curtiss was named as an inventor. Before working with the AEA, Curtiss resented being called an inventor, stating that "An inventor, as people in country towns thought of him, was a wild-eyed, impractical person, with ideas that wouldn't work". Clearly, the success of the June Bug and the AEA changed Curtiss' way of thinking because Curtiss would go on to be an inventor on more than 84 patents, many of which were directed to pioneering inventions in the field of aviation. In 2003, Curtiss was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Postscript:

Noticeably absent from the foregoing discussion of aviation milestones is any mention of the Wright brothers and their Flyer. When the Wright brothers first flew the Flyer at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903, the event was a private affair. There were only five witnesses and no reporters. Indeed, the iconic photograph of the first flight was not published until May of 1908. Even then, it was not clear from thephotograph whether the Flyer was merely gliding or flying under its own power. In May of 1904, the Wright brothers invited the public and reporters to witness a demonstration of their Flyer at Huffman Prairie, near Dayton, Ohio. The demonstration was a failure and hugely embarrassing to the Wright brothers because, try as they might, they could not get the Flyer off the ground. The failure at Huffman Prairie coupled with the nature of the first flight at Kitty Hawk and the Wright's obsession with secrecy caused people to seriously question whether the Wright brothers had actually flown.

One of the more milder skeptics of the Wright brothers was the Scientific American magazine, who sponsored the Trophy that was eventually won by the June Bug. The Trophy was, in part, intended to urge the Wright brother to publicly demonstrate a successful flight of the Flyer. The Wright brothers would have none of it though. They were too busy preparing for aircraft trials with the Army and perhaps, more importantly, could not meet one of the requirements for winning the Trophy: the aircraft had to take off from level ground under its own power. In 1908, the Flyer could still only become airborne after being launched from a track through the use of a catapult. Indeed, it was not until the introduction of the Model B in 1910 that the Flyer was fitted with wheels and could take off on its own without assistance.

On August 8, 1908, Wilbur Wright finally flew the Flyer in public at the Hunaudieres race course, five miles south of Le Mans, France.