Alfred Nobel

Alfred Nobel

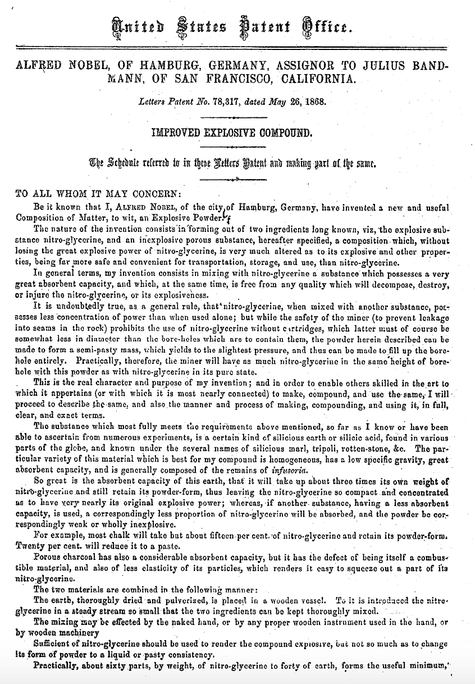

On May 26, 1868, U.S. Patent No.: 78,317 issued to Swedish-born Alfred Nobel for what would later become known as dynamite. Nobel's invention comprised mixing nitroglycerine with what Alfred called "silicious marl, tripoli, rottenstone", which is typically powdered limestone mixed with silica. While quite simple, the invention was incredibly useful; it retained most of the explosive power of nitroglycerine but rendered it much safer to handle and easier to use. Alfred found that a composition consisting of 75% by weight nitroglycerine and 25% by weight rottenstone was ideal in terms of handling and explosive power. In his patent, Alfred noted that his inventive composition was safer to handle, store and transport than gunpowder. When the composition was exposed to open air in ordinary packing and set on fire, it would burn but not detonate, unlike gunpowder. To detonate the composition, it had to be tightly confined in packaging and then exploded by a percussion cap ignited by a blasting fuse.

Alfred had grown up around explosives and munitions, being the son of an arms manufacturer, Immanuel Nobel, who sold munitions to Russia during the Crimea War. Indeed, it was Immanuel's floating mines that helped protect St. Petersburg from being bombarded by British warships during that war. In order to better supply the Russians, Immanuel moved his family to Russia, where Alfred and his brothers were educated at home by Swedish and Russian tutors. Alfred became well educated, especially in chemistry, and learned to speak five languages, but never attended university or received a degree. He did, however, travel and study throughout Europe, including working in the Paris laboratory of Théophile Pelouze, where Alfred became acquainted with the Italian chemist, Ascanio Sobrero, who had invented nitroglycerin in 1846.

During his studies, Alfred dedicated himself to developing a way to safely manufacture and use nitroglycerine. His work took on more importance after his younger brother, Emil, was killed in a nitroglycerine explosion in 1864. Alfred's dedication paid off in 1867, when he came up with his formulation of dynamite. In addition to the U.S., Alfred patented his invention in the UK and Sweden.

Alfred made a fortune from dynamite and other explosive-related inventions he made. He assigned the '317 patent to Julius Bandmann of San Francisco, who formed the Giant Powder Company for the express purpose of manufacturing and selling dynamite in the U.S., from which Alfred received royalties. Later, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (DuPont) purchased the Giant Powder Company to expand its explosives product line to include dynamite. In 1912, however, DuPont's explosives business was found to be a monopoly and was broken up.

Alfred's invention of dynamite revolutionized the mining and construction industries. Since it was much more powerful than black powder and easier to handle, dynamite facilitated large-scale projects and made them much safer. The invention of dynamite, however, had a darker side. Almost as soon as it was invented, dynamite's potential for use as a weapon of violence was recognized. Alfred recognized this potential, but naively believed that such use would be too terrible to be contemplated by civilized people, stating: “My dynamite will sooner lead to peace than a thousand world conventions. As soon as men will find that in one instant, whole armies can be utterly destroyed, they surely will abide by golden peace.”

Alfred's naive belief was quickly dispelled in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871 when Prussian forces utilized dynamite to destroy French fortifications with deadly effect. Before the war, Alfred had tried to introduce his dynamite to France, but was blocked by a French government monopoly on explosives, resulting in a technological mismatch between Prussia and France. This mismatch was not the sole reason Prussia defeated France in the war, but it clearly played a major role.

Anarchists and political radicals also used dynamite to advance their causes through terrorist bombings. A bomb made of dynamite was used by radicals to assassinate the reformist Czar Alexander II of Russia in March of 1881 and a dynamite bomb was used to kill 7 police officers and 4 bystanders at Haymarket Square in Chicago on May 4, 1886.

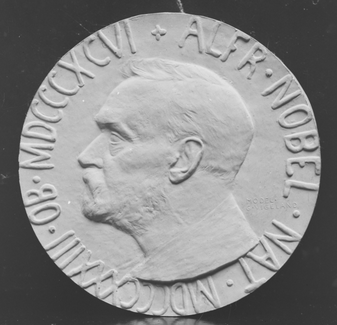

The destructive and violent uses of dynamite greatly disturbed Alfred and motivated him to provide in his will that most of his large estate be used for annual awards in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature and peace, which he valued greatly.

Alfred had grown up around explosives and munitions, being the son of an arms manufacturer, Immanuel Nobel, who sold munitions to Russia during the Crimea War. Indeed, it was Immanuel's floating mines that helped protect St. Petersburg from being bombarded by British warships during that war. In order to better supply the Russians, Immanuel moved his family to Russia, where Alfred and his brothers were educated at home by Swedish and Russian tutors. Alfred became well educated, especially in chemistry, and learned to speak five languages, but never attended university or received a degree. He did, however, travel and study throughout Europe, including working in the Paris laboratory of Théophile Pelouze, where Alfred became acquainted with the Italian chemist, Ascanio Sobrero, who had invented nitroglycerin in 1846.

During his studies, Alfred dedicated himself to developing a way to safely manufacture and use nitroglycerine. His work took on more importance after his younger brother, Emil, was killed in a nitroglycerine explosion in 1864. Alfred's dedication paid off in 1867, when he came up with his formulation of dynamite. In addition to the U.S., Alfred patented his invention in the UK and Sweden.

Alfred made a fortune from dynamite and other explosive-related inventions he made. He assigned the '317 patent to Julius Bandmann of San Francisco, who formed the Giant Powder Company for the express purpose of manufacturing and selling dynamite in the U.S., from which Alfred received royalties. Later, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (DuPont) purchased the Giant Powder Company to expand its explosives product line to include dynamite. In 1912, however, DuPont's explosives business was found to be a monopoly and was broken up.

Alfred's invention of dynamite revolutionized the mining and construction industries. Since it was much more powerful than black powder and easier to handle, dynamite facilitated large-scale projects and made them much safer. The invention of dynamite, however, had a darker side. Almost as soon as it was invented, dynamite's potential for use as a weapon of violence was recognized. Alfred recognized this potential, but naively believed that such use would be too terrible to be contemplated by civilized people, stating: “My dynamite will sooner lead to peace than a thousand world conventions. As soon as men will find that in one instant, whole armies can be utterly destroyed, they surely will abide by golden peace.”

Alfred's naive belief was quickly dispelled in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871 when Prussian forces utilized dynamite to destroy French fortifications with deadly effect. Before the war, Alfred had tried to introduce his dynamite to France, but was blocked by a French government monopoly on explosives, resulting in a technological mismatch between Prussia and France. This mismatch was not the sole reason Prussia defeated France in the war, but it clearly played a major role.

Anarchists and political radicals also used dynamite to advance their causes through terrorist bombings. A bomb made of dynamite was used by radicals to assassinate the reformist Czar Alexander II of Russia in March of 1881 and a dynamite bomb was used to kill 7 police officers and 4 bystanders at Haymarket Square in Chicago on May 4, 1886.

The destructive and violent uses of dynamite greatly disturbed Alfred and motivated him to provide in his will that most of his large estate be used for annual awards in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature and peace, which he valued greatly.