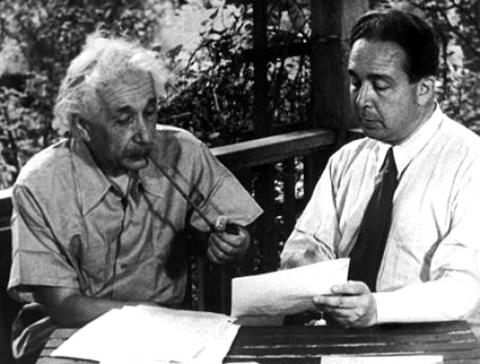

Einstein and Szilard, Photo by NavioZuber

Einstein and Szilard, Photo by NavioZuber

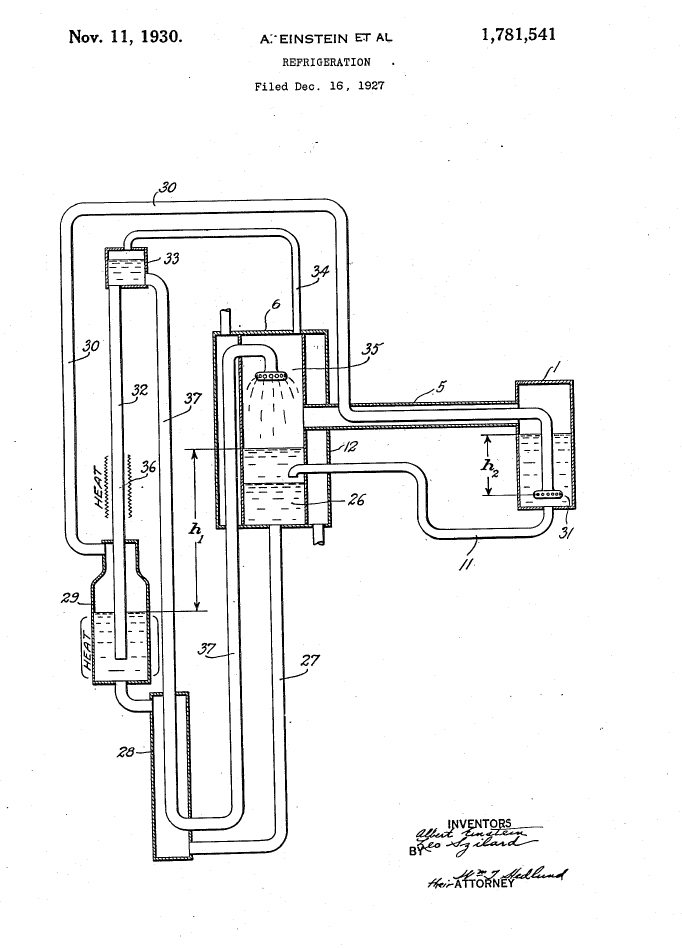

On November 11 of the year 1930, U.S. Patent No.: 1,781,541 issued to Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard for an invention simply entitled "Refrigeration". At the time, both Szilard and Einstein were living in Berlin, Germany. Szilard lectured at the Institute of Theoretical Physics, while Einstein worked on his theory of general relativity at the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Szilard had attended Einstein's lectures and the two had become close friends. Einstein was already world-famous, having published his theory of special relativity in 1905 and his theory of general relativity in 1915. In addition, Einstein had won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect. Szilard's fame would come later for his work with nuclear chain reactions.

Einstein and Szilard were motivated to work on developing new methods and apparatus for refrigeration after reading a newspaper account detailing how an entire family had been killed in Berlin by toxic fumes leaking from their refrigerator. Unfortunately, this was not an uncommon occurrence at the time. The refrigerants that were being used were toxic, corrosive, and/or flammable and included ammonia, sulfur dioxide, chloromethane, propane and isobutane.

To reduce the hazards of refrigeration, Einstein and Szilard did not invent a new refrigerant. Instead, they invented a refrigeration system that had no moving parts, which they believed would prevent seal failure and, thus, leaking. The system they developed only required a heat source and operated on the absorption principle, using an inert gas, ammonia and water. Their system was based on a constant pressure absorption system invented earlier by Swedish inventors Baltzar von Platen and Carl Munters in 1922 (see U.S. Patent No.: 1,620,843). One of the differences between the two systems was that the Einstein/Szilard system used butane as the inert gas, while the Platen-Munters system used hydrogen. In both systems, cooling was obtained by the evaporation of the ammonia, which was thereafter absorbed into the water. The inert gas was used to lower the partial pressure of the ammonia, which allowed the ammonia to evaporate at the low temperature the refrigerator was designed to work at.

Just as the Einstein/Szilard refrigeration system was about to be commercialized, a new refrigerant, Freon, was discovered by a team at General Motors, headed by noted engineer Thomas Midgley. At the time of its introduction, Freon (dichlorodifluoromethane) was considered a miracle compound because of its excellent refrigerant properties and the belief that it was non-toxic to humans. As such, Freon became widely adopted in refrigeration systems, thereby obviating the need for the Einstein/Szilard refrigerator.

Einstein and Szilard were motivated to work on developing new methods and apparatus for refrigeration after reading a newspaper account detailing how an entire family had been killed in Berlin by toxic fumes leaking from their refrigerator. Unfortunately, this was not an uncommon occurrence at the time. The refrigerants that were being used were toxic, corrosive, and/or flammable and included ammonia, sulfur dioxide, chloromethane, propane and isobutane.

To reduce the hazards of refrigeration, Einstein and Szilard did not invent a new refrigerant. Instead, they invented a refrigeration system that had no moving parts, which they believed would prevent seal failure and, thus, leaking. The system they developed only required a heat source and operated on the absorption principle, using an inert gas, ammonia and water. Their system was based on a constant pressure absorption system invented earlier by Swedish inventors Baltzar von Platen and Carl Munters in 1922 (see U.S. Patent No.: 1,620,843). One of the differences between the two systems was that the Einstein/Szilard system used butane as the inert gas, while the Platen-Munters system used hydrogen. In both systems, cooling was obtained by the evaporation of the ammonia, which was thereafter absorbed into the water. The inert gas was used to lower the partial pressure of the ammonia, which allowed the ammonia to evaporate at the low temperature the refrigerator was designed to work at.

Just as the Einstein/Szilard refrigeration system was about to be commercialized, a new refrigerant, Freon, was discovered by a team at General Motors, headed by noted engineer Thomas Midgley. At the time of its introduction, Freon (dichlorodifluoromethane) was considered a miracle compound because of its excellent refrigerant properties and the belief that it was non-toxic to humans. As such, Freon became widely adopted in refrigeration systems, thereby obviating the need for the Einstein/Szilard refrigerator.