Gamed

The History of the Monopoly® Board Game

October 2018

Monopoly® Board Game

Monopoly® Board Game

It was a great story. An unemployed salesman, in the darkest depths of the depression, invents a board game that becomes wildly popular and lifts the salesman out of poverty and transforms him into a millionaire. What made the story even better is that it was true, well at least most of it was. It was the 1930s, the board game was Monopoly® and the salesman, Charles Darrow, really was unemployed and became a millionaire from his sale of Monopoly®. Unfortunately, the most important part of the story was false. Charles Darrow did not invent Monopoly®. Read on to learn more; its a Patently Interesting story!

Charles Darrow

(By BullsandBears)

Charles Darrow

(By BullsandBears)

The Story

According to Monopoly lore that held sway for more than fifty years, Charles Darrow, after becoming unemployed, would spend his days in his Philadelphia home inventing games, both to amuse himself and to hopefully generate some money. In late 1931 or so, Charles got the idea of a real estate trading game after hearing about a university course where the professor gave his class script to invest and then graded them on their imaginary investments. Charles’ game took physical shape on the Darrow family’s oil cloth table covering, with Charles painting different properties on the oil cloth, fashioning houses and hotels from scraps of discarded wood and typing up property deeds on miscellaneous pieces of cardboard. Even though he lived in Philadelphia, Charles named the properties on his board after streets in Atlantic City because of fond memories Charles had of better times spent vacationing in Atlantic City. Soon friends and family gathered around the Darrow kitchen table to play the new game Charles had created, which he called “Monopoly”. The game quickly became a sensation, which prompted Charles to sell the game to Parker Brother for over a million dollars. Charles had done well by his self-proclaimed “brain child”, which, as we shall see, was most definitely a misnomer.

According to Monopoly lore that held sway for more than fifty years, Charles Darrow, after becoming unemployed, would spend his days in his Philadelphia home inventing games, both to amuse himself and to hopefully generate some money. In late 1931 or so, Charles got the idea of a real estate trading game after hearing about a university course where the professor gave his class script to invest and then graded them on their imaginary investments. Charles’ game took physical shape on the Darrow family’s oil cloth table covering, with Charles painting different properties on the oil cloth, fashioning houses and hotels from scraps of discarded wood and typing up property deeds on miscellaneous pieces of cardboard. Even though he lived in Philadelphia, Charles named the properties on his board after streets in Atlantic City because of fond memories Charles had of better times spent vacationing in Atlantic City. Soon friends and family gathered around the Darrow kitchen table to play the new game Charles had created, which he called “Monopoly”. The game quickly became a sensation, which prompted Charles to sell the game to Parker Brother for over a million dollars. Charles had done well by his self-proclaimed “brain child”, which, as we shall see, was most definitely a misnomer.

Elizabeth Magie

Elizabeth Magie

The Real Story

- The real story of the Monopoly board game begins with Lizie J. Magie, who was a forward-thinking woman, with wide-ranging interests in engineering, poetry, writing, acting and game design. She was a graduate of the Belasco theater school of acting and had a flair for the dramatic. At one point, Lizie created a national sensation by placing a newspaper advertisement offering herself for sale to the highest bidder as an “American slave”. She did so to ostensibly draw attention to the plight of American workers in general and women workers in particular. Some of the more interesting passages in her advertisement included:

- “Brunette; large gray green eyes; full passionate lips; splendid teeth, not beautiful, but very attractive, features full of character and strength, yet truly feminine; height 5 feet, 3 inches; well proportioned, graceful, simple.”

- “Age, well she is not very old, but she was not born yesterday”.

- “Artistic temperament; warm, generous hearted; kind, gentle, affectionate disposition; at times bubbling over with merriment and vivacity; then again dignified, sedate, studious, or perhaps bowed down with grief at the wrongs and miseries of her fellow creatures.”

- “She can hardly add up a column of figures without making a mistake - but can write a good story.”

- “She can’t sweep a room without tiring herself out - but she can sit up all night to work out some point in her inventions.”

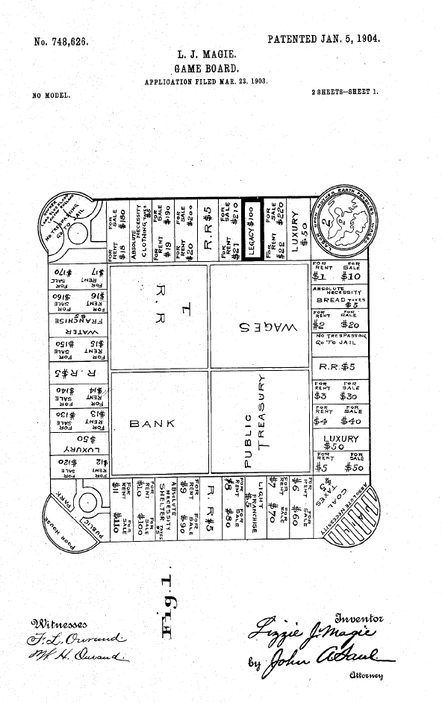

U.S. Patent No.: 748,626

U.S. Patent No.: 748,626

In order to highlight the problems of a rentier economy, Lizie developed a board game she called the “Landlord’s Game”. Lizie believed it was “[A] practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences”. Lizie filed a patent application for the landlord’s game on March 23, 1903. On January 5, 1904, the patent application issued as U.S. Patent No. 748,626. It is rather ironic that Lizie filed for and received a patent on the landlord’s game, considering how Henry George considered patents to be monopolies and against the moral law.

The Landlord’s Game, as described in the ‘626 patent, was an interesting game and way ahead of its time. Being so novel, the claims of the ‘626 patent were very broad and would have covered the later Monopoly game. The Landlord’s Game had many of the elements of the Monopoly game, including play money and a board with an endless, rectangular path divided into series of delimited spaces, some of which were properties that could be bought by players, some were utility spaces and some were railroad spaces. There was also a corner public park space (analogous to the “Free Parking” space of the Monopoly game), a corner “go to jail space” and a wages space (analogous to the “GO” space of the Monopoly game - see below). Players moved checkers around the path based on throws of a pair of dice. When a property was first landed on by a player, the player could buy the property or rent it. If the player bought the property, they would get a deed for the property and any subsequent player who landed on the property had to pay the owner player a minimum rent. The game was designed for four people and would conclude when the last player passed the beginning-point the fifth time.

Some of the features of the Monopoly game that were not present in the Landlord’s game were the grouping of properties (by color or otherwise) and the increase of rent based on a player’s ownership of a property grouping and the presence of buildings (houses and hotels).

The Landlord’s Game did not overtly promote Georgism or the single tax system. Indeed the ‘626 patent stated that “[t]he object of the game is to obtain as much wealth or money as possible, the player having the greatest amount of wealth at the end of the game after a certain predetermined number of circuits of the board have been made being the winner”. However, Lizie gave a nod to Georgism with the corner “wages” space, which when passed by a player would result in the player being paid $100 in wages. On the board, this space had the phrase: “labor upon mother earth produces wages”. This phrase was a homage to Henry George’s belief “[t]hat wages, instead of being drawn from capital, are in reality drawn from the product of the labor for which they are paid”. This belief was in contrast to Adam Smith’s wages fund theory, which held that wages flowed from savings (capital).

The Landlord’s Game, as described in the ‘626 patent, was an interesting game and way ahead of its time. Being so novel, the claims of the ‘626 patent were very broad and would have covered the later Monopoly game. The Landlord’s Game had many of the elements of the Monopoly game, including play money and a board with an endless, rectangular path divided into series of delimited spaces, some of which were properties that could be bought by players, some were utility spaces and some were railroad spaces. There was also a corner public park space (analogous to the “Free Parking” space of the Monopoly game), a corner “go to jail space” and a wages space (analogous to the “GO” space of the Monopoly game - see below). Players moved checkers around the path based on throws of a pair of dice. When a property was first landed on by a player, the player could buy the property or rent it. If the player bought the property, they would get a deed for the property and any subsequent player who landed on the property had to pay the owner player a minimum rent. The game was designed for four people and would conclude when the last player passed the beginning-point the fifth time.

Some of the features of the Monopoly game that were not present in the Landlord’s game were the grouping of properties (by color or otherwise) and the increase of rent based on a player’s ownership of a property grouping and the presence of buildings (houses and hotels).

The Landlord’s Game did not overtly promote Georgism or the single tax system. Indeed the ‘626 patent stated that “[t]he object of the game is to obtain as much wealth or money as possible, the player having the greatest amount of wealth at the end of the game after a certain predetermined number of circuits of the board have been made being the winner”. However, Lizie gave a nod to Georgism with the corner “wages” space, which when passed by a player would result in the player being paid $100 in wages. On the board, this space had the phrase: “labor upon mother earth produces wages”. This phrase was a homage to Henry George’s belief “[t]hat wages, instead of being drawn from capital, are in reality drawn from the product of the labor for which they are paid”. This belief was in contrast to Adam Smith’s wages fund theory, which held that wages flowed from savings (capital).

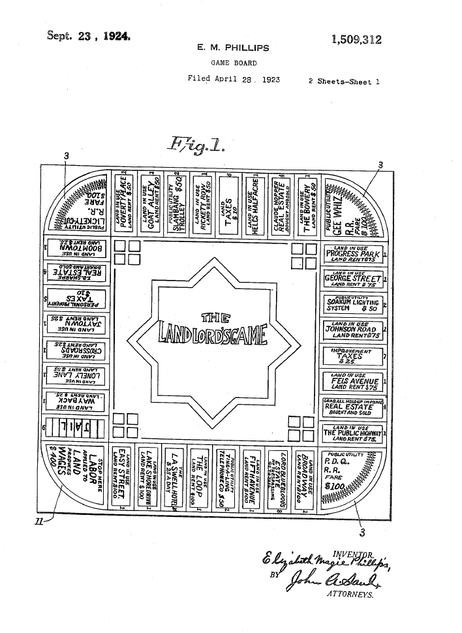

U.S. Patent No.: 1,509,312

U.S. Patent No.: 1,509,312

Lizie spent significant effort trying to commercialize the Landlord’s Game. A family acquaintance even speculated that her advertisement to sell herself was nothing more than a stunt to gain free publicity to boost sales of the Landlord’s Game. At one point, in 1909, Lizie submitted the game to Parker Brothers, who rejected the game as being too complicated. In 1921, Lizie’s ‘626 patent in the Landlord’s Game expired. Perhaps to keep an interest in the game, Lizie revised the Landlord’s Game and filed another patent application for the revised game in 1923. On September 23, 1924, U.S. Patent No.: 1,509,312 issued to Lizie (who was now married with the last name Phillips) for the revised Landlord’s Game.

In some ways, the revised Landlord’s Game (as emdbodied in the ‘312 patent) was less similar to the later Monopoly game than the original Landlord’s Game. The corner public park space and the corner “go to jail space” were gone. In addition, the concept of land-in-use spaces and idle land spaces was introduced. Moreover, the land-in-use spaces (upon which rent was paid) could not be purchased by a player simply landing on the space first and paying the purchase price. The land-in-use spaces were partially allocated to players at the beginning of the game through cards dealt to players. Thereafter, if a party landed on a land-in-use space that was not owned (via the initially-dealt cards), the space was put up for bid to all players, with the space being awarded to the highest bidder.

While overall moving away from the later Monopoly game, the revised Landlord’s Game did introduce additional features of the later Monopoly game. Play money with different-colored denominations was introduced, as was the concept of increasing rents by adding improvements to land-in-use spaces and increasing the charges for landing on a utility when all utilities were owned by a single player. The feature of increased rents/charges was broadly captured by Claim 1 of the ‘312 patent and would cover the later Monopoly game.

The revised Landlord’s Game more prominently promoted Georgism and the single tax system. The ‘312 patent boldly stated that: “[t]he object of the game is not only to afford amusement to the players, but to illustrate to them how under the present or prevailing system of land tenure, the landloard has an advantage over other enterprises and also how the single tax would discourage land speculation.” The board spaces also included “George street” and “Fels Avenue”. Joseph Fels was a wealthy businessman who was a financial benefactor of the single tax movement.

Lizie’s efforts to commercialize the revised Landlord’s Game were no more successful than with the original game. However, in the 1920s, the Landlord’s Game did make its way to several eastern universities, one of which was Williams College. At Williams, a homemade variant of the Landlord’s Game was enthusiastically embraced by fraternity brothers Daniel Layman and Ferdinand and Louis Thun, who spread the game to many of their friends, including a man by the name of Pete Daggett. Daniel and the Thun brothers referred to the game as the “Monopoly game”; unaware that it had originated from the Landlord’s Game. Daniel and the Thun brothers made their own changes to the game, such as using miniature houses, having groupings of properties and increasing rents based on the presence of houses and/or ownership of a group of properties. As such, their game was very similar to the later Monopoly game.

After graduating from Williams College, Daniel tried to market the game under the name “Fascinating Game of Finance” (later shortened to just “Finance”) through a company called Electronic Laboratories Inc. Daniel chose to use the name Finance after consulting with his attorneys, who counseled against using the name “Monopoly” because of prior use of the name. The attorneys also advised against seeking patent protection because of Lizie’s prior patents. As with Lizie, Daniel’s marketing efforts were not very successful. Eventually, Daniel gave up and sold his interest in the Finance game for $200 to a friend, Brooke Lerch, who, in turn, sold it to the Knapp Electric Corporation, a manufacturer of mainly educational and technology-based toys and games.

Even though Daniel’s marketing efforts ultimately failed, the Monopoly game developed by Daniel and the Thun brothers made its way to Atlantic City via Pete Daggett, who taught the game to Ruth Hoskins in Indianapolis. Ruth moved from Indianapolis to Atlantic City to teach at a Quaker school. Ruth and her Quaker friends adopted the game and made it their own by implementing a number of changes, the most important being the use of property names of Atlantic City streets and locales. The changes made by the Atlantic City Quakers essentially resulted in the Monopoly game that we know today, except for the artwork and tokens. It was at this point in its development that the Monopoly game was introduced to Charles Darrow by Charles and Olive Todd, who had learned it from relatives of some of the Atlantic City Quakers.

In some ways, the revised Landlord’s Game (as emdbodied in the ‘312 patent) was less similar to the later Monopoly game than the original Landlord’s Game. The corner public park space and the corner “go to jail space” were gone. In addition, the concept of land-in-use spaces and idle land spaces was introduced. Moreover, the land-in-use spaces (upon which rent was paid) could not be purchased by a player simply landing on the space first and paying the purchase price. The land-in-use spaces were partially allocated to players at the beginning of the game through cards dealt to players. Thereafter, if a party landed on a land-in-use space that was not owned (via the initially-dealt cards), the space was put up for bid to all players, with the space being awarded to the highest bidder.

While overall moving away from the later Monopoly game, the revised Landlord’s Game did introduce additional features of the later Monopoly game. Play money with different-colored denominations was introduced, as was the concept of increasing rents by adding improvements to land-in-use spaces and increasing the charges for landing on a utility when all utilities were owned by a single player. The feature of increased rents/charges was broadly captured by Claim 1 of the ‘312 patent and would cover the later Monopoly game.

The revised Landlord’s Game more prominently promoted Georgism and the single tax system. The ‘312 patent boldly stated that: “[t]he object of the game is not only to afford amusement to the players, but to illustrate to them how under the present or prevailing system of land tenure, the landloard has an advantage over other enterprises and also how the single tax would discourage land speculation.” The board spaces also included “George street” and “Fels Avenue”. Joseph Fels was a wealthy businessman who was a financial benefactor of the single tax movement.

Lizie’s efforts to commercialize the revised Landlord’s Game were no more successful than with the original game. However, in the 1920s, the Landlord’s Game did make its way to several eastern universities, one of which was Williams College. At Williams, a homemade variant of the Landlord’s Game was enthusiastically embraced by fraternity brothers Daniel Layman and Ferdinand and Louis Thun, who spread the game to many of their friends, including a man by the name of Pete Daggett. Daniel and the Thun brothers referred to the game as the “Monopoly game”; unaware that it had originated from the Landlord’s Game. Daniel and the Thun brothers made their own changes to the game, such as using miniature houses, having groupings of properties and increasing rents based on the presence of houses and/or ownership of a group of properties. As such, their game was very similar to the later Monopoly game.

After graduating from Williams College, Daniel tried to market the game under the name “Fascinating Game of Finance” (later shortened to just “Finance”) through a company called Electronic Laboratories Inc. Daniel chose to use the name Finance after consulting with his attorneys, who counseled against using the name “Monopoly” because of prior use of the name. The attorneys also advised against seeking patent protection because of Lizie’s prior patents. As with Lizie, Daniel’s marketing efforts were not very successful. Eventually, Daniel gave up and sold his interest in the Finance game for $200 to a friend, Brooke Lerch, who, in turn, sold it to the Knapp Electric Corporation, a manufacturer of mainly educational and technology-based toys and games.

Even though Daniel’s marketing efforts ultimately failed, the Monopoly game developed by Daniel and the Thun brothers made its way to Atlantic City via Pete Daggett, who taught the game to Ruth Hoskins in Indianapolis. Ruth moved from Indianapolis to Atlantic City to teach at a Quaker school. Ruth and her Quaker friends adopted the game and made it their own by implementing a number of changes, the most important being the use of property names of Atlantic City streets and locales. The changes made by the Atlantic City Quakers essentially resulted in the Monopoly game that we know today, except for the artwork and tokens. It was at this point in its development that the Monopoly game was introduced to Charles Darrow by Charles and Olive Todd, who had learned it from relatives of some of the Atlantic City Quakers.

Charles Darrow recognized the worth of the Monopoly game he had learned from the Todds and decided to market the game. First, however, he enlisted the help of an artist friend to change the artwork to be more visually appealing. Charles soon started getting requests for copies of the game from friends and family he had introduced the game to. He obliged these requests by making and selling copies of the “Monopoly” game for $4 a piece. Charles also started offering the “Monopoly” game to department stores in Philadelphia. The success of the “Monopoly” game prompted Charles to file an application for copyright registration of a version of the board on October 24, 1933. The application stated that July 30, 1933 was the first date of publication of that particular version of the board. However, other versions of the board had been sold before that date.

In 1934, Charles tried to sell the Monopoly game to Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers, both of whom initially rejected the game. Parker Brothers, however, changed its mind in early 1935, after the popularity of the Monopoly game was boosted by its appearance in the F.A.O. Schwarz catalog. Parker Brothers quickly worked out a deal with Charles pursuant to which Parker Brothers bought all of Charles’ rights in the “monopoly” game for $7,000, plus royalties.

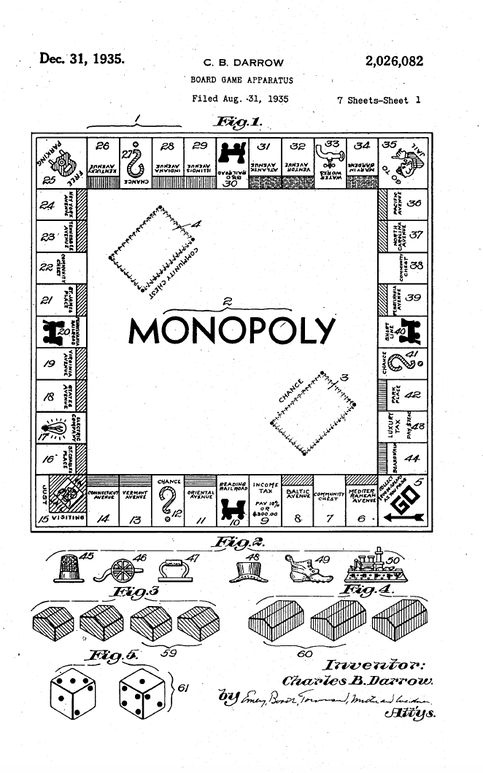

To protect their investment, Parker Brothers filed in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, first a trademark application for “MONOPOLY” on March 30, 1935 and then a patent application for the Monopoly game on August 31, 1935.

In accordance with U.S. patent law, the patent application was filed in the name of Charles Darrow, but was assigned to Parker Brothers. Initially, the patent application was rejected on two grounds. The first ground was that the game was “of no practical value or utility” and was “frivolous or injurious to public morals”. The second ground was that the game was not patentable over Lizie’s two patents.

Parker Brothers responded to the first ground of rejection by calling it “absurd” and noting the inconsistency of the Patent Office in not similarly rejecting Lizie's two patents. Parker Brothers also asserted that the (Monopoly) game was being sold on the market “to an amazing extent” and that it was “played not only by young people but by professional men with a great deal of instruction and interest”.

With regard to the second rejection based on Lizie's patents, Parker Brothers responded by highlighting the features not disclosed in Lizie's patents and arguing that these "features co-act to produce a new result, which is an improvement (as a result) upon what is disclosed in [Lizie's two patents]". The features that Parker Brothers highlighted included the miniature buildings, the Chance cards, the tokens and the grouping of properties by color or design.

Parker Brother's arguments were successful and the patent application issued as U.S. Patent No. 2,026,082 on December 31, 1935, a mere four months after it was filed. The trademark application had previously issued in July of 1935 as trademark registration (No. 0326723). The patent expired in 1952, but the trademark registration remains in force to this day.

To further protect their investment in the Monopoly game, Parker Brothers bought Lizie’s rights in the Landlord’s Game and her second patent (the '312 patent), as well as the rights of the Knapp Electric Corporation in the Finance game. In another instance of “life is not fair”, Parker Brothers paid Knapp Electric Corporation $10,000, but paid Lizie only $500. What makes this disparity so obscene is that Parker Brothers notified the Patent Office, during the prosecution of Charles' patent application, that they owned Lizie's '312 patent and admitted that it covered their (Monopoly) game.

While quite generous, the amount Parker Brothers paid to the Knapp Electric Corporation pales in comparison to the money Charles Darrow and his heirs received in royalties from Parker Brothers. In 1962, Charles estimated he had already received over a million dollars in royalties from Parker Brothers and the money was still coming in. Indeed, the royalties were still coming in decades after Charles death in 1967. Of course, the money Parker Brothers and now Hasbro (the current owner of the Monopoly game) have made and continue to make from the Monopoly game are many orders of magnitude greater than the money Charles Darrow and his heirs received.

At this point in the (real) story, you, the reader, must be wondering how all of this could have happened. How could Charles have gotten fabulously wealthy from a game he did not invent? Well, it was a combination of many things: Charles was at the right place at the right time, he astutely recognized the value of the monopoly game, he made it more sleek and visually appealing, and he doggedly pursued its marketing. Oh, and he lied. He lied to Parker Brothers that he was the inventor of the Monopoly game. He also lied to the U.S. Patent Office by signing a false oath that he was the “original, first, and sole inventor” of the game.

Needless to say, Parker Brothers was not completely innocent in the whole affair either. They suspected that Charles did not invent the Monopoly game; they knew about the prior sales of the Finance game; and they knew about the publication of the Monopoly game on July 30, 1933. If the U.S. Patent Office had been made aware of any one of these three facts, they would not have issued the ‘082 patent to Charles. A patent for an invention can only issue to its inventor; the prior public use of the Finance game would have been anticipating prior art, i.e., would have rendered the Monopoly game old and not patentable; and the publication of the Monopoly game by Charles more than two years before the filing date of the patent application would have been a bar to obtaining a patent. (At the time, a patent application for an invention had to be filed within two years of the invention’s public disclosure). Parker Brothers did not disclose any of the aforementioned facts to the Patent Office. At the time, however, Parker Brothers did not have an affirmative duty to do so. A rule requiring a duty to disclose such information to the Patent Office was not implemented until 1977.

While Charles Darrow did not invent the Monopoly game and his conduct was not the most forthcoming, we should keep in mind that if not for Charles Darrow, the Monopoly game would probably never have been introduced and embraced by the world in the manner it has been, which would have made the world that much less fun. But the next time you play Monopoly, think of Lizie Magie and her gray green eyes, and when you pass go and collect $200, think of Henry George, who tried to end poverty.

In 1934, Charles tried to sell the Monopoly game to Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers, both of whom initially rejected the game. Parker Brothers, however, changed its mind in early 1935, after the popularity of the Monopoly game was boosted by its appearance in the F.A.O. Schwarz catalog. Parker Brothers quickly worked out a deal with Charles pursuant to which Parker Brothers bought all of Charles’ rights in the “monopoly” game for $7,000, plus royalties.

To protect their investment, Parker Brothers filed in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, first a trademark application for “MONOPOLY” on March 30, 1935 and then a patent application for the Monopoly game on August 31, 1935.

In accordance with U.S. patent law, the patent application was filed in the name of Charles Darrow, but was assigned to Parker Brothers. Initially, the patent application was rejected on two grounds. The first ground was that the game was “of no practical value or utility” and was “frivolous or injurious to public morals”. The second ground was that the game was not patentable over Lizie’s two patents.

Parker Brothers responded to the first ground of rejection by calling it “absurd” and noting the inconsistency of the Patent Office in not similarly rejecting Lizie's two patents. Parker Brothers also asserted that the (Monopoly) game was being sold on the market “to an amazing extent” and that it was “played not only by young people but by professional men with a great deal of instruction and interest”.

With regard to the second rejection based on Lizie's patents, Parker Brothers responded by highlighting the features not disclosed in Lizie's patents and arguing that these "features co-act to produce a new result, which is an improvement (as a result) upon what is disclosed in [Lizie's two patents]". The features that Parker Brothers highlighted included the miniature buildings, the Chance cards, the tokens and the grouping of properties by color or design.

Parker Brother's arguments were successful and the patent application issued as U.S. Patent No. 2,026,082 on December 31, 1935, a mere four months after it was filed. The trademark application had previously issued in July of 1935 as trademark registration (No. 0326723). The patent expired in 1952, but the trademark registration remains in force to this day.

To further protect their investment in the Monopoly game, Parker Brothers bought Lizie’s rights in the Landlord’s Game and her second patent (the '312 patent), as well as the rights of the Knapp Electric Corporation in the Finance game. In another instance of “life is not fair”, Parker Brothers paid Knapp Electric Corporation $10,000, but paid Lizie only $500. What makes this disparity so obscene is that Parker Brothers notified the Patent Office, during the prosecution of Charles' patent application, that they owned Lizie's '312 patent and admitted that it covered their (Monopoly) game.

While quite generous, the amount Parker Brothers paid to the Knapp Electric Corporation pales in comparison to the money Charles Darrow and his heirs received in royalties from Parker Brothers. In 1962, Charles estimated he had already received over a million dollars in royalties from Parker Brothers and the money was still coming in. Indeed, the royalties were still coming in decades after Charles death in 1967. Of course, the money Parker Brothers and now Hasbro (the current owner of the Monopoly game) have made and continue to make from the Monopoly game are many orders of magnitude greater than the money Charles Darrow and his heirs received.

At this point in the (real) story, you, the reader, must be wondering how all of this could have happened. How could Charles have gotten fabulously wealthy from a game he did not invent? Well, it was a combination of many things: Charles was at the right place at the right time, he astutely recognized the value of the monopoly game, he made it more sleek and visually appealing, and he doggedly pursued its marketing. Oh, and he lied. He lied to Parker Brothers that he was the inventor of the Monopoly game. He also lied to the U.S. Patent Office by signing a false oath that he was the “original, first, and sole inventor” of the game.

Needless to say, Parker Brothers was not completely innocent in the whole affair either. They suspected that Charles did not invent the Monopoly game; they knew about the prior sales of the Finance game; and they knew about the publication of the Monopoly game on July 30, 1933. If the U.S. Patent Office had been made aware of any one of these three facts, they would not have issued the ‘082 patent to Charles. A patent for an invention can only issue to its inventor; the prior public use of the Finance game would have been anticipating prior art, i.e., would have rendered the Monopoly game old and not patentable; and the publication of the Monopoly game by Charles more than two years before the filing date of the patent application would have been a bar to obtaining a patent. (At the time, a patent application for an invention had to be filed within two years of the invention’s public disclosure). Parker Brothers did not disclose any of the aforementioned facts to the Patent Office. At the time, however, Parker Brothers did not have an affirmative duty to do so. A rule requiring a duty to disclose such information to the Patent Office was not implemented until 1977.

While Charles Darrow did not invent the Monopoly game and his conduct was not the most forthcoming, we should keep in mind that if not for Charles Darrow, the Monopoly game would probably never have been introduced and embraced by the world in the manner it has been, which would have made the world that much less fun. But the next time you play Monopoly, think of Lizie Magie and her gray green eyes, and when you pass go and collect $200, think of Henry George, who tried to end poverty.

Proudly powered by Weebly