The Lung

September 2018

The S-4 Submarine

The S-4 Submarine

In December of 1927, the nation’s attention was riveted on the cold grey waters of the Atlantic, off the coast of Provincetown, Massachusetts. Over one hundred feet below the waves, the USS S-4 submarine lay crippled on the ocean floor, the victim of a collision with the Coast Guard destroyer Paulding. Six crew members were known to be alive in the forward torpedo room and rescue attempts were underway in a bid to save them. For five days, the rescue attempts continued, but to no avail. Ultimately, the six men perished, together with the other 34 members of the S-4’s crew. The sad fact was that, at the time, the U.S. Navy did not have the technology to rescue sailors from sunken submarines. The S-4 tragedy strengthened the resolve of one man to develop this technology. Through ingenuity and patently brave determination, the man succeeded. Read on to learn more; it’s a Patently Interesting story!

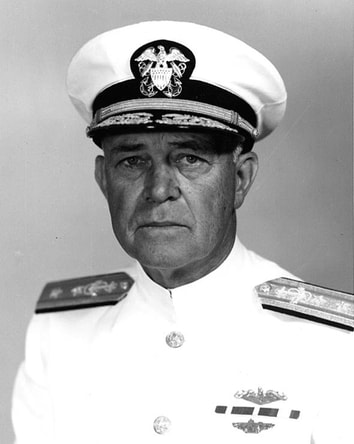

Two years before the loss of the S-4, the USS S-51 submarine had been sunk after being rammed by the merchant steamer City of Rome near Block Island. Thirty-three crew members of the S-51 perished in that accident. Several of these men were friends of Charles Bowers Momsen, who, as captain of the USS S-1 helped find the sunken S-51. For Momsen, the sight of one his friend’s bodies retrieved from the S-51 forever became etched in his mind. The man’s fingers were torn raw from a vain attempt to open a hatch held closed by tons of ocean water. This horrifying image drove Momsen to find a way to help submariners escape from stricken craft.

Momsen’s initial idea was to provide a large bell-shaped rescue chamber that would be lowered from a surface rescue ship using guide cables secured between the rescue ship and the sunken submarine. The bell would be positioned over one of two escape hatches located on the deck of the submarine and then secured to the deck. Once the bell was so positioned, the pressure in the bell would be reduced to provide a seal between the bell and a flat steel plate welded to the deck around the escape hatch. A rubber gasket on the bottom of the rescue chamber would help make this seal water tight. With the bell sealed against the submarine, the escape hatch could be opened to permit the men in the submarine to climb into the bell and thereafter be ferried to the surface.

Momsen submitted his bell idea to Captain Ernest J. King, the base commander at the Naval Submarine Base New London, who endorsed the idea and forwarded it to the Navy’s Bureau of Construction and Repair. Momsen then waited. And waited and waited. He was greeted with nothing but silence. He began to question the feasibility of the bell and suspected that it had been rejected for some technical flaw that he had overlooked. As it turned out, that was not the case at all. In fact, no one had even looked at his idea.

In a twist of fate, Momsen was transferred to the Bureau of Construction and Repair in April of 1927, almost a year after he had submitted his rescue bell idea to them. On his very first day at the Bureau, Momsen went through a file filled with papers titled “AWAITING ACTION” that had been left by his predecessor. There, at the bottom of the file, was Momsen’s proposal for the rescue bell. At first Momsen was filled with anger, but he quickly channeled his anger into action. He doggedly pursued the rescue bell idea within the Bureau, only to be rebuffed at every turn. At one point, he came into the office to find his proposal dumped on his desk, accompanied by a note reading: “Impractical from the standpoint of seamanship”. Momsen continued to champion his idea, but eventually it was finally rejected, just weeks before the S-4 tragedy.

The S-4 tragedy was particularly painful for Momsen. As he read the heartbreaking dispatches from the failed rescue operation, Momsen couldn’t help but think that his rescue bell could have saved the men trapped in the S-4. However, it would get worse, much worse. After the rescue operation failed and it was acknowledged that all the men on the S-4 had died, the recriminations began. Angry letters poured in to the Navy, accusing them of negligence and demanding an investigation. It was cruel irony that Momsen was tasked with answering these letters, an unenviable task that would be the low point of his career. However, it steeled Momsen’s resolve to find a way to save trapped submariners; a way that wouldn’t require him to rely on government bureaucracy. Fortuitously, another idea came to him that would allow him to do so.

The idea itself mirrored Momsen’s decision not to rely on government help. Instead of developing a device that would require trapped submariners to rely on rescue from the outside, Momsen would develop a device that would allow them to escape on their own from the inside. The idea took the form of a bag that would be worn by a submariner and from which the submariner could breathe air during his escape from his stricken craft. To develop this concept, Momsen enlisted the help of a civilian employee of the Bureau of Construction and Repair, Frank Hobson, as well as Clarence Tibbals, who was the head of the Navy's diving school at the Washington Navy Yard. The first step Hobson took was to review the available technology. At the time, it was known that both the British and the Germans had submarine escape devices, but they were complicated to use and/or too bulky. Momsen and Hobson wanted something compact and easy to use. (N1)

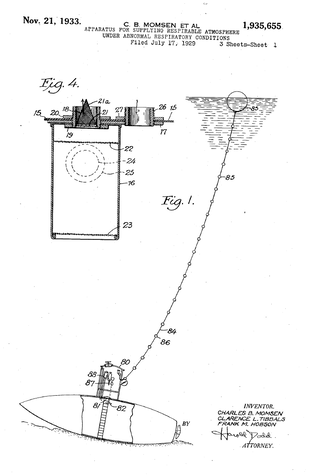

Hobson, Tibbals and Momsen set to work to develop what would later become known as the (Momsen) Lung. The Lung was a closed circuit breathing apparatus that featured a rubber breathing bag that was to be initially charged with oxygen from a pressurized tank. The breathing bag was connected to a rubber mouthpiece by inhalation and exhalation tubes fitted with oppositely-directed one-way valves. The inhalation tube was connected to the breathing bag directly, whereas the exhalation tube was connected to the breathing bag by a canister of soda lime, which absorbed carbon dioxide. In this manner, a submariner, using the mouthpiece, would inhale air/oxygen from the interior of the breathing bag through the inhalation tube and exhale air into the canister through the exhalation tube. After being scrubbed of carbon dioxide inside the canister, the exhaled air would return to the breathing bag. Importantly, the breathing bag was provided with a pressure relief valve to permit the release of air when a submariner ascended from deep water.

Once the design and construction of a prototype of the Lung was completed, Momsen personally tested the Lung to ensure that it worked. First, Momsen tested the Lung under controlled conditions, at the Washington Navy Yard, in a model boat basin and then a pressurized dive tank. These tests were successful, so Momsen decided to test the Lung in open water using a crudely constructed diving chamber. He chose the muddy Potomac river as the location for the test. The diving chamber was nothing more than a small steel box with a platform mounted underneath its open bottom. With Momsen ensconced inside, the diving chamber was lowered into the murky river, where the platform and the lower part of Momsen's legs sank into the fetid mud of the river bottom. Although initially distracted by the total darkness and rancid smell that engulfed him, Momsen quickly gathered himself together and filled the Lung with oxygen from a small tank he had brought with him. He then exited the diving chamber and rose to the surface without incident. His test was a success! Momsen had escaped from a structure that had been sunk to a depth of 110 feet, which was the precise depth at which the S-4 had suffered its fate. However, one test still remained: escaping from an actual submarine.

Momsen's succesful demonstration of the Lung in the muddy Potomac caught the attention of the news media and, thus, the upper echelon of the Navy. Seeing how favorable the response was to Momsen's exploits, the Navy quickly endorsed Momsen's development of the Lung, as well as Momsen's original idea for a rescue bell. Needless to say, Momsen quickly became quite busy. While continuing to test the Lung, Momsen also worked on developing the rescue bell.

The salvaged S-4

The salvaged S-4

In February of 1929, Momsen got his chance to test the Lung in an escape from an actual submarine. And it wasn't just any ordinary submarine. It was the resurrected S-4. Several months after it had sunk, the S-4 had been salvaged and towed to the Charlestown Navy Yard, where it had remained until Momsen persuaded the Navy to let him use it for testing. Momsen made a number of modifications to the S-4 for his tests, the most important of which was the installation of a cylindrical steel skirt around the hatch inside the engine room.

The S-4 was towed to a location off the coast of Key West and sunk with Ed Kalinoski, a Navy torpedoman, and Momsen inside. Once the S-4 reached the bottom, Momsen and Kalinoski retreated to the engine room and sealed themselves inside. They donned their Lungs and then prepared to escape. Kalinoski unlocked the hatch and then Momsen proceeded to open flood valves that allowed the ocean water to flow into the engine room. One can only imagine the thoughts that must have run through their heads. Here they were at the bottom of the ocean, trapped in a sunken submarine that had already carried 40 men to their deaths, watching the water rise precipitously around them, not knowing whether their escape plan would really work. Not surprisingly, Kalinoski blurted out to Momsen: "I hope to Christ you know what you are doing".

A loud crash announced that the hatch had been blown open by the increasing pressure in the engine room. Enormous air bubbles escaped through the hatch and the water in the engine room rose even faster. Right when the water reached the bottom of their chins, it stopped rising. The water had reached the bottom of the steel skirt, which had stopped the inflow of water by preventing any more air from escaping through the hatch, just as Momsen had predicted. Momsen and Kalinoski charged their Lungs with oxygen and then exited the S-4 through the open hatch, rising to the surface, all the while normally inhaling and exhaling using the Lung. Once again, the Lung was proven successful and demonstrated that escape from a stricken submarine was indeed possible.

The S-4 was towed to a location off the coast of Key West and sunk with Ed Kalinoski, a Navy torpedoman, and Momsen inside. Once the S-4 reached the bottom, Momsen and Kalinoski retreated to the engine room and sealed themselves inside. They donned their Lungs and then prepared to escape. Kalinoski unlocked the hatch and then Momsen proceeded to open flood valves that allowed the ocean water to flow into the engine room. One can only imagine the thoughts that must have run through their heads. Here they were at the bottom of the ocean, trapped in a sunken submarine that had already carried 40 men to their deaths, watching the water rise precipitously around them, not knowing whether their escape plan would really work. Not surprisingly, Kalinoski blurted out to Momsen: "I hope to Christ you know what you are doing".

A loud crash announced that the hatch had been blown open by the increasing pressure in the engine room. Enormous air bubbles escaped through the hatch and the water in the engine room rose even faster. Right when the water reached the bottom of their chins, it stopped rising. The water had reached the bottom of the steel skirt, which had stopped the inflow of water by preventing any more air from escaping through the hatch, just as Momsen had predicted. Momsen and Kalinoski charged their Lungs with oxygen and then exited the S-4 through the open hatch, rising to the surface, all the while normally inhaling and exhaling using the Lung. Once again, the Lung was proven successful and demonstrated that escape from a stricken submarine was indeed possible.

Submariner with Momsen Lung

Submariner with Momsen Lung

Momsen continued to perform escape tests from the S-4, at increasing depths; his deepest escape being performed at an incredible 206 feet below the waves. He also developed an escape chamber or trunk that was mounted below a hatch. The escape trunk could be flooded and pressurized separate from an entire compartment. The success of Momsen's tests convinced the Navy to modify its submarines to have escape trunks and to be equipped with a sufficient supply of Lungs for the men onboard. More importantly, submariners were trained on how to use the Lung to escape from a stricken submarine.

In May of 1929, Momsen and Tibbals were each awarded the Navy's Distinguished Service Medal for their efforts in developing and testing the Lung. Being a civilian, Hobson was instead given a year's salary as a reward. Four years later, the U.S. Patent Office awarded Momsen, Tibbals and Hobson U.S. Patent No. 1,935,655 for an "Apparatus for Supplying Respirable Atmosphere under Abnormal Respiratory Conditions", i.e. the Lung. The patent issued from a patent application they had filed in July of 1929.

In May of 1929, Momsen and Tibbals were each awarded the Navy's Distinguished Service Medal for their efforts in developing and testing the Lung. Being a civilian, Hobson was instead given a year's salary as a reward. Four years later, the U.S. Patent Office awarded Momsen, Tibbals and Hobson U.S. Patent No. 1,935,655 for an "Apparatus for Supplying Respirable Atmosphere under Abnormal Respiratory Conditions", i.e. the Lung. The patent issued from a patent application they had filed in July of 1929.

USS Tang

USS Tang

From 1929 through 1956, the U.S. Navy used the Lung as its standard submarine escape equipment. During this time, the Lung was only used once to escape from a sunken submarine under emergency conditions. The escape occurred in October of 1944 from the USS Tang, which was one of the most successful U.S. submarines in World War II. On the night of October 24-25, the Tang made a surface attack on a large Japanese convoy in the Formosa Straits. After sinking a number of ships in the convoy, the Tang fired her last torpedo, which, to the horror of her crew went rogue and circled back on the Tang, striking her abreast the after torpedo room. The resulting explosion was so violent that it threw nine crew members who were on the bridge into the water. As the Tang slipped stern first beneath the waves, a tenth crew member escaped from the conning tower. The remaining crew members were trapped in the Tang as she sank to the bottom in 180 feet of water.

Inside the sunken submarine, chaos reigned. The aft three compartments were destroyed and/or flooded and a fire broke out in the forward battery compartment. To make matters worse, the Japanese started depth charging the crippled submarine. Nonetheless, thirty of the survivors (some of whom were severely injured) were able to make it to the forward torpedo room, where an escape trunk was located. Once the depth charging stopped, the survivors attempted their escape. Two of the survivors couldn't wait for the Lungs to be passed out and went through the escape trunk without any equipment. They were never seen again. Some of the survivors were too injured to try an escape and some just gave up. As such, only thirteen men escaped from the sunken submarine. Unfortunately, only eight of them made it to the surface and only five were able to stay afloat long enough to be rescued. All five of these men had used the Lung to make their escape.

Of the ten crew members of the Tang who had initially been thrown in the water, only four were able to swim long enough to be rescued. These four men plus the five who had escaped from the sunken submarine were picked up by a Japanese destroyer escort, which had also rescued survivors of the Japanese ships sunk by the Tang. These Japanese survivors, many of whom were burned or otherwise injured, proceeded to beat the nine Tang survivors. Fortunately, the Tang survivors lived through these beatings and their subsequent incarceration in a Japanese prisoner of war camp.

Although submarine escapes had occurred before the development of the Lung and the Lung was only used once to save the lives of trapped submariners, Momsen's determination and bravery in developing and testing the Lung showed the world that escape from a sunken submarine was possible. Before Momsen demonstrated the effectiveness of the Lung, most submariners believed that a sunken submarine was an "iron coffin". Momsen dispelled this notion and gave them hope.

Notes:

(N1) What Hobson and Momsen probably did not know was that both the British and the Germans were also developing new submarine escape devices that were very similar to what Momsen would develop. The new British device was known as the Davis Submarine Escape Apparatus (DSEA), while the German device was known as the Gegunlunge (counter lung) or Tauchretter.

Inside the sunken submarine, chaos reigned. The aft three compartments were destroyed and/or flooded and a fire broke out in the forward battery compartment. To make matters worse, the Japanese started depth charging the crippled submarine. Nonetheless, thirty of the survivors (some of whom were severely injured) were able to make it to the forward torpedo room, where an escape trunk was located. Once the depth charging stopped, the survivors attempted their escape. Two of the survivors couldn't wait for the Lungs to be passed out and went through the escape trunk without any equipment. They were never seen again. Some of the survivors were too injured to try an escape and some just gave up. As such, only thirteen men escaped from the sunken submarine. Unfortunately, only eight of them made it to the surface and only five were able to stay afloat long enough to be rescued. All five of these men had used the Lung to make their escape.

Of the ten crew members of the Tang who had initially been thrown in the water, only four were able to swim long enough to be rescued. These four men plus the five who had escaped from the sunken submarine were picked up by a Japanese destroyer escort, which had also rescued survivors of the Japanese ships sunk by the Tang. These Japanese survivors, many of whom were burned or otherwise injured, proceeded to beat the nine Tang survivors. Fortunately, the Tang survivors lived through these beatings and their subsequent incarceration in a Japanese prisoner of war camp.

Although submarine escapes had occurred before the development of the Lung and the Lung was only used once to save the lives of trapped submariners, Momsen's determination and bravery in developing and testing the Lung showed the world that escape from a sunken submarine was possible. Before Momsen demonstrated the effectiveness of the Lung, most submariners believed that a sunken submarine was an "iron coffin". Momsen dispelled this notion and gave them hope.

Notes:

(N1) What Hobson and Momsen probably did not know was that both the British and the Germans were also developing new submarine escape devices that were very similar to what Momsen would develop. The new British device was known as the Davis Submarine Escape Apparatus (DSEA), while the German device was known as the Gegunlunge (counter lung) or Tauchretter.

Proudly powered by Weebly