William Allen

William Allen

On July 15 of the year 1954, the Boeing Model 367-80 made its maiden flight from Boeing Field in Seattle. The Model 367-80, called the Dash 80 by its crew, was the prototype of America's first jet airliner, the Boeing 707. The construction of the Dash 80 was spearheaded by Boeing president, William Allen, at a time when there was little demand for new commercial airliners, particularly jet airliners. Most of the major air carriers had recently acquired new propeller-driven airliners and jet aircraft were viewed with suspicion. The world's first jet airliner, the British de Havilland Comet, had gone into service in May of 1952, but had experienced problems from the start, and was temporarily withdrawn from service in 1954 after a series of crashes.

Despite the unfavorable atmosphere, Allen pushed the development of the Dash 80 because he was confident that jet aircraft were the future of commercial air service. In addition, he knew that Boeing could not compete with the Douglas Aircraft Company in the production of propeller-driven airliners. In the realm of jet aircraft, however, Boeing had an advantage over Douglas. Boeing had gained invaluable knowledge and experience from the development and construction of the B-47 and B-52, which were large multi-engine jet bombers.

The most important body of knowledge that Boeing carried over from the B-47 and the B-52 to the Dash 80 was the design of the wings and the engine mounts. The wings and the tail of the Dash 80 were provided with the same 35-degree sweep as the B-47 and the B-52, which Boeing knew, from research, was optimal and gave the Dash 80 increased speed. The engines of the Dash 80 were mounted in pods on pylons below the wings, the same as the B-47 and the B-52. This mounting left room in the wings for fuel tanks and would permit the pod to break away in the event of a crash landing, without damaging the wing or rupturing a fuel tank.

While Boeing was able to reuse a lot of technology from the B-47 and the B-52 in the Dash 80, there were several areas where Boeing had to develop new technology. One of these areas was in the landing of the Dash 80 and, more particularly, stopping the Dash 80 after it landed. Propeller-driven aircraft could reverse their propellers to help stop the aircraft, a feature that could not be employed by the Dash 80 and other jet aircraft. The B-47 and B-52 had the advantage of being able to use long military runways and employing drag chutes to stop. This advantage would not be available to the Dash 80, so technology had to be developed for quickly and safely stopping the Dash 80.

Despite the unfavorable atmosphere, Allen pushed the development of the Dash 80 because he was confident that jet aircraft were the future of commercial air service. In addition, he knew that Boeing could not compete with the Douglas Aircraft Company in the production of propeller-driven airliners. In the realm of jet aircraft, however, Boeing had an advantage over Douglas. Boeing had gained invaluable knowledge and experience from the development and construction of the B-47 and B-52, which were large multi-engine jet bombers.

The most important body of knowledge that Boeing carried over from the B-47 and the B-52 to the Dash 80 was the design of the wings and the engine mounts. The wings and the tail of the Dash 80 were provided with the same 35-degree sweep as the B-47 and the B-52, which Boeing knew, from research, was optimal and gave the Dash 80 increased speed. The engines of the Dash 80 were mounted in pods on pylons below the wings, the same as the B-47 and the B-52. This mounting left room in the wings for fuel tanks and would permit the pod to break away in the event of a crash landing, without damaging the wing or rupturing a fuel tank.

While Boeing was able to reuse a lot of technology from the B-47 and the B-52 in the Dash 80, there were several areas where Boeing had to develop new technology. One of these areas was in the landing of the Dash 80 and, more particularly, stopping the Dash 80 after it landed. Propeller-driven aircraft could reverse their propellers to help stop the aircraft, a feature that could not be employed by the Dash 80 and other jet aircraft. The B-47 and B-52 had the advantage of being able to use long military runways and employing drag chutes to stop. This advantage would not be available to the Dash 80, so technology had to be developed for quickly and safely stopping the Dash 80.

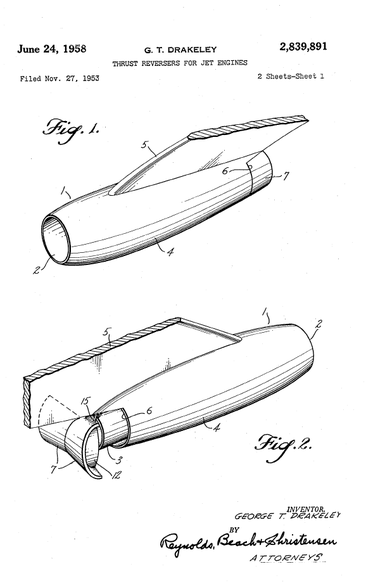

U.S. Patent No.: 2,839,891

U.S. Patent No.: 2,839,891

The technology that Boeing developed for stopping the Dash 80 was a thrust reverser for a jet engine, which was the subject of U.S. Patent No. 2,839,891 to Drakeley. The thrust reverser included a pair of flaps mounted adjacent to a tailpipe of an engine. The flaps were curved and included baffles. The flaps were movable between an inoperative position and an operative position. In the inoperative position, the flaps were disposed alongside the tailpipe so as to mostly encircle the tailpipe and form part of the streamlined engine housing. In the operative position, the flaps were disposed to the rear of and directed outwardly from the longitudinal axis of the tailpipe. In the inoperative position, the flaps did not interfere with the discharge of gases from the tailpipe, whereas when the flaps were in the operative position, the flaps would deflect the gases from the tailpipe outwardly and forwardly, thereby helping stop forward movement of the aircraft.

After its initial flight on July 15, the Dash 80 was demonstrated to airline executives and other notables in the aircraft industry. In one infamous demonstration in August of 1954, Allen arranged to have the Dash 80 fly over Lake Washington, where the Gold Cup hyrdoplane races were being held. Airline executives from all over the world were present at the races and Allen wanted to impress them with a simple flyover of the Dash 80. What they got instead was an aerial acrobatic exhibition. The pilot of the Dash 80, Alvin "Tex" Johnston did two barrel rolls over the games. While the stunt impressed the airline executives, it infuriated Allen, who fired Johnston numerous times that day. Allen later forgave Johnston, but would never allow the stunt to be discussed in his presence from that day forward.

Apparently, Johnston's acrobatic stunt worked because orders for the 707 began to arrive in early 1955. However, it would be another two years before the 707's started rolling off the production line. In 1958, the 707 entered commercial airline service and remained in such service in the U.S. until 1983.

After its initial flight on July 15, the Dash 80 was demonstrated to airline executives and other notables in the aircraft industry. In one infamous demonstration in August of 1954, Allen arranged to have the Dash 80 fly over Lake Washington, where the Gold Cup hyrdoplane races were being held. Airline executives from all over the world were present at the races and Allen wanted to impress them with a simple flyover of the Dash 80. What they got instead was an aerial acrobatic exhibition. The pilot of the Dash 80, Alvin "Tex" Johnston did two barrel rolls over the games. While the stunt impressed the airline executives, it infuriated Allen, who fired Johnston numerous times that day. Allen later forgave Johnston, but would never allow the stunt to be discussed in his presence from that day forward.

Apparently, Johnston's acrobatic stunt worked because orders for the 707 began to arrive in early 1955. However, it would be another two years before the 707's started rolling off the production line. In 1958, the 707 entered commercial airline service and remained in such service in the U.S. until 1983.