Thomas Edison in 1878

Thomas Edison in 1878

On July 29 of the year 1878, a total solar eclipse occurred over western North America, extending from Alaska, across western Canada and the United States, from Montana through Texas. The occurrence of the eclipse was known well in advance and attracted many people, including a number of notable scientists and inventors. Two of these notables were Thomas Alva Edison and James Craig Watson. Edison needs no introduction, but Watson is a much less well-known figure, especially outside astronomy circles. Edison went to the eclipse ostensibly to test a new invention, while Watson was on a quest to find a planet. Both failed, but only Edison realized it.

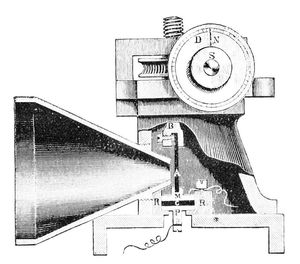

Edison had developed a device he called a micro-tasimeter, which he claimed could detect changes in temperature as small as 1/50,000 of a degree. The micro-tasimeter included a three-inch horn, which was intended to reflect heat on a hard rubber rod. An increase in heat would cause the rod to expand and press down on a carbon button connected into an electrical circuit. The pressure on the carbon button would change the resistance and, thus, the current in the electrical circuit, which was then detected by a connected galvanometer.

Edison committed to providing a micro-tasimeter to Henry Draper of New York University, who intended to use the device to measure minute temperature changes in heat emitted from the Sun's corona during the eclipse. In order to help ensure that Edison kept his commitment, Edison was invited to accompany Draper to Wyoming to view the eclipse. Anxious to get out of his laboratory and travel out west, Edison accepted the invitation.

Edison had developed a device he called a micro-tasimeter, which he claimed could detect changes in temperature as small as 1/50,000 of a degree. The micro-tasimeter included a three-inch horn, which was intended to reflect heat on a hard rubber rod. An increase in heat would cause the rod to expand and press down on a carbon button connected into an electrical circuit. The pressure on the carbon button would change the resistance and, thus, the current in the electrical circuit, which was then detected by a connected galvanometer.

Edison committed to providing a micro-tasimeter to Henry Draper of New York University, who intended to use the device to measure minute temperature changes in heat emitted from the Sun's corona during the eclipse. In order to help ensure that Edison kept his commitment, Edison was invited to accompany Draper to Wyoming to view the eclipse. Anxious to get out of his laboratory and travel out west, Edison accepted the invitation.

James Craig Watson

James Craig Watson

Watson was a brilliant astronomer at the University of Michigan (UM) who had been an intellectual child prodigy. He had no real formal schooling until he entered UM as a freshman at the age of 15 because he had been smarter than his erstwhile teachers. In 1863, Watson became professor of astronomy and director of the Detroit Observatory at UM. At some point, Watson became obsessed with proving the existence of the planet Vulcan, which was believed to circle the sun within the orbit of Mercury.

A number of prominent astronomers believed that Vulcan existed due to anomalies in Mercury's orbit. The foremost proponent of Vulcan had been Urbain Le Verrier, the late director of the Paris Observatory, who was famous for having predicted the existence and position of Neptune using only mathematics. Le Verrier had made his prediction to explain discrepancies with Uranus' orbit and the laws of physics. Using similar calculations, Le Verrier had gone on to predict the presence of Vulcan to explain the anomalies in Mercury's orbit. After having confirmed some of Le Verrier's observations and calculations, Watson became a firm believer in the existence of Vulcan.

When Watson was invited by Rear Admiral John Rodgers of the U.S. Naval Observatory to travel to Wyoming to view the eclipse, Watson jumped at the chance. He informed Rodgers of his intentions, stating: "I think I had better search for the intra mercurial planet during the totality, as so many observers will pay attention to the Corona."

A number of prominent astronomers believed that Vulcan existed due to anomalies in Mercury's orbit. The foremost proponent of Vulcan had been Urbain Le Verrier, the late director of the Paris Observatory, who was famous for having predicted the existence and position of Neptune using only mathematics. Le Verrier had made his prediction to explain discrepancies with Uranus' orbit and the laws of physics. Using similar calculations, Le Verrier had gone on to predict the presence of Vulcan to explain the anomalies in Mercury's orbit. After having confirmed some of Le Verrier's observations and calculations, Watson became a firm believer in the existence of Vulcan.

When Watson was invited by Rear Admiral John Rodgers of the U.S. Naval Observatory to travel to Wyoming to view the eclipse, Watson jumped at the chance. He informed Rodgers of his intentions, stating: "I think I had better search for the intra mercurial planet during the totality, as so many observers will pay attention to the Corona."

Edison micro-tasimeter

Edison micro-tasimeter

In the early afternoon of July 29, 1878, both Watson and Edison prepared themselves for the coming eclipse in Wyoming. At 3:13 PM, local time, the totality of the eclipse occurred. While dogs barked and chickens went to roost, Edison connected the battery in his micro-tasimeter to measure the change in heat. The needle of the tasimeter jumped and then started to gyrate uncontrollably. It was detecting heat, and lots of it, but most likely it was coming from nearby bystanders. The micro-tasimeter was too sensitive and failed to provide any meaningful measure of the heat from the corona of the sun.

Meanwhile, Watson fixed the eclipsed sun in the viewing center of his telescope and then started a predetermined scan. He quickly found what he was looking for. As he explained to a reporter: "Fortunately, however, it was situated in the region which I had deteremined to sweep over. I found, about a minute before the end of the total solar eclipse, a star of the 4 1/2 magnitude, which immediately arrested my attention from its general appearance and place, in which there is no known star. It had a disk larger than the spurious disk of a star, and shone with a ruddy light. There was no elongation, such as would be presented by a comet in that position, and hence I feel warranted in announcing it as an interior planet." Watson was confident he had not made an errant sighting, confidently assuring the reporter: "[The planet's] position in reference to the sun and a neighboring star I determined by a method which obviates the possibility of an error, so that I am able to assign its position with certainty."

Watson's putative discovery of Vulcan was heralded by the newspapers as a great scientific discovery that would "hold a conspicuous place in the annals of science". Others were not so confident. Almost immediately after Watsons' announcement, other notable astronomers began to question Watson's sighting and openly expressed skepticism of it. Some even resorted to outright mockery. Determined to silence his critics, Watson embarked on a mission to build a special underground observatory, which he mistakenly believed would help him observe planets, including Vulcan, in the daytime. Watson's mission ultimately led to his untimely death in 1880 at the young age of 42.

While Watson never realized he had failed to find Vulcan, Edison knew his micro-tasimeter was a failure, at least commercially. Believing it was nothing more than a scientific curiosity, Edison never bothered to patent the micro-tasimeter and allowed others to copy it freely.

Meanwhile, Watson fixed the eclipsed sun in the viewing center of his telescope and then started a predetermined scan. He quickly found what he was looking for. As he explained to a reporter: "Fortunately, however, it was situated in the region which I had deteremined to sweep over. I found, about a minute before the end of the total solar eclipse, a star of the 4 1/2 magnitude, which immediately arrested my attention from its general appearance and place, in which there is no known star. It had a disk larger than the spurious disk of a star, and shone with a ruddy light. There was no elongation, such as would be presented by a comet in that position, and hence I feel warranted in announcing it as an interior planet." Watson was confident he had not made an errant sighting, confidently assuring the reporter: "[The planet's] position in reference to the sun and a neighboring star I determined by a method which obviates the possibility of an error, so that I am able to assign its position with certainty."

Watson's putative discovery of Vulcan was heralded by the newspapers as a great scientific discovery that would "hold a conspicuous place in the annals of science". Others were not so confident. Almost immediately after Watsons' announcement, other notable astronomers began to question Watson's sighting and openly expressed skepticism of it. Some even resorted to outright mockery. Determined to silence his critics, Watson embarked on a mission to build a special underground observatory, which he mistakenly believed would help him observe planets, including Vulcan, in the daytime. Watson's mission ultimately led to his untimely death in 1880 at the young age of 42.

While Watson never realized he had failed to find Vulcan, Edison knew his micro-tasimeter was a failure, at least commercially. Believing it was nothing more than a scientific curiosity, Edison never bothered to patent the micro-tasimeter and allowed others to copy it freely.