A Brief History of the Tea Bag

April 2018

The invention of the tea bag is typically attributed to Thomas Sullivan, a New York tea importer, who, as the story goes, decided in 1908 that he could save money by sending out samples of his tea to prospective customers in silk bags instead of the then-customary tin canisters. His intention was to have customers remove the tea leaves from the bags and use them to make tea in the traditional manner. However, to Mr. Sullivan’s surprise, the customers did not remove the tea from the bags, but instead plopped the bags with the tea still inside into boiling water, thereby completing the invention of the tea bag. Whether this story is true is difficult to ascertain. No contemporaneous accounts of Mr. Sullivan’s discovery have been found. What is certain, however, is that Mr. Sullivan did not invent the tea bag in 1908. Read on to learn more; its a Patently Interesting story!

As with most products, the modern tea bag is the culmination of a series of incremental developments or inventions made by a number of different people extending back many years.The progression to the modern tea bag was not linear from a technological standpoint. Some developments facilitated production, but detracted from usefulness and vice versa. Still other developments emphasized features that failed to gain commercial acceptance.

An early reference to the use of a bag to make tea can be found in the July 1836 edition of the Preston Temperance Advocate, which was a temperance magazine started by the noted temperance campaigner, Joseph Livesey. Tea played a prominent role in the temperance movement and was routinely served at meetings in large quantities, even though Methodist founder John Wesley, who helped inspire the temperance movement, also abstained from drinking tea because it caused him to experience “Symptoms of a Paralytick Disorder”. The Advocate describes the process for making tea for the temperance meetings or “tea parties” as follows: "At the tea-parties in Birmingham they made the tea in large tins, about a yard square, and a foot deep, each one containing as much as will serve about 250 persons. The tea is tied loosely in bags, about 1/4 lb in each. At the top there is an aperture, into which the boiling water is conveyed by a pipe from the boiler, and at one corner there is a tap, from which the tea when brewed is drawn out. It may be either sweetened or milked, or both, if thought best, while in the tins. Being thus made, it can be carried in teapots, or jugs, where those cannot be bad. Capital tea was made at the last festival by this plan.”

As with most products, the modern tea bag is the culmination of a series of incremental developments or inventions made by a number of different people extending back many years.The progression to the modern tea bag was not linear from a technological standpoint. Some developments facilitated production, but detracted from usefulness and vice versa. Still other developments emphasized features that failed to gain commercial acceptance.

An early reference to the use of a bag to make tea can be found in the July 1836 edition of the Preston Temperance Advocate, which was a temperance magazine started by the noted temperance campaigner, Joseph Livesey. Tea played a prominent role in the temperance movement and was routinely served at meetings in large quantities, even though Methodist founder John Wesley, who helped inspire the temperance movement, also abstained from drinking tea because it caused him to experience “Symptoms of a Paralytick Disorder”. The Advocate describes the process for making tea for the temperance meetings or “tea parties” as follows: "At the tea-parties in Birmingham they made the tea in large tins, about a yard square, and a foot deep, each one containing as much as will serve about 250 persons. The tea is tied loosely in bags, about 1/4 lb in each. At the top there is an aperture, into which the boiling water is conveyed by a pipe from the boiler, and at one corner there is a tap, from which the tea when brewed is drawn out. It may be either sweetened or milked, or both, if thought best, while in the tins. Being thus made, it can be carried in teapots, or jugs, where those cannot be bad. Capital tea was made at the last festival by this plan.”

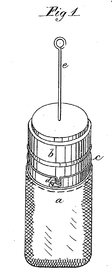

U.S. Patent No. 234,556

U.S. Patent No. 234,556

Jumping forward forty or so years to the year 1880, an early precursor of the modern tea bag was described in U.S. Patent No.: 234,556, which issued to Thomas Fitzgerald of Boston. This precursor was comprised of a porous bag composed of muslin or cloth secured to a float. The bag could be removed from the float to permit tea or coffee to be inserted or removed from the bag. An elongated handle was attached to the float.

In the 1890’s, it became fairly well known to use porous cloth bags to make individual cups of tea. Descriptions of this use can be found in a number of newspaper articles from the time. As such, patents began to appear for improvements on this basic concept.

In the 1890’s, it became fairly well known to use porous cloth bags to make individual cups of tea. Descriptions of this use can be found in a number of newspaper articles from the time. As such, patents began to appear for improvements on this basic concept.

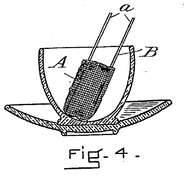

U.S. Patent No. 489,468

U.S. Patent No. 489,468

One such patent was U.S. Patent No. 489,468 to Edward Gillingham of Chelsea Massachusetts, which issued on January 10, 1893. The Gillingham patent was directed to a “Tea-Strainer” that took the form of a bag formed from strainer cloth that was filled with a quantity of coffee or tea. A U-shaped wire was inserted into the bag such that the bag rested against the loop in the wire. In this manner, the parallel legs of the wire extended from the bag and acted as a handle to facilitate the dunking and removal of the bag from a cup, as shown. The purported benefit of the strainer was that it was “compact, containing enough coffee or tea to make one or more cups, and can be carried in the pocket or sent by mail if desired”.

U.S. Patent No.: 723,287

U.S. Patent No.: 723,287

Another patent was U.S. Patent No.: 723,287, which was granted on March 24, 1903 to Roberta C. Lawson and Mary McLaren of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The patent was directed to a “Tea Leaf Holder” comprised of a pocket made of open mesh fabric, such as cotton thread. The pocket had an open end through which tea leaves could be inserted into the pocket. A flap closed the open end and was secured in place by a piece of wire. The purpose of the tea leaf holder was “to provide means whereby a small quantity of tea, so much only as is required for a single cup of tea, can be placed in a cup and have water poured thereon to produce only a cup of tea fresh for immediate use”. In other words, to provide a single serving or individual tea “bag”.

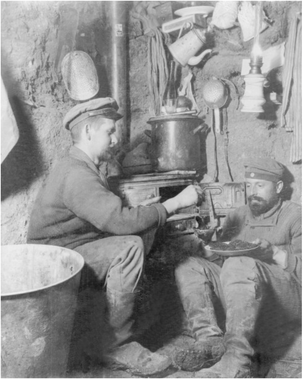

German Soldiers with Teebombe

German Soldiers with Teebombe

While individual tea bags were known well before 1908, they were not mass-produced until World War 1. During that time, a German company called Teekanne GmbH began mass producing Teebombes (“tea bombs”), which were distributed to German troops on the front lines, as well as to civilians. These tea bombs were round, hand-sewn bags composed of cotton gauze and filled with tea and a small amount of sugar. The open ends of the bags were tied closed with pieces of string. Apparently, the German troops called them “tea bombs” because they turned the water brown, but did not impart much tea flavor.

Tea containers similar to the German “tea bombs” were also manufactured and sold in the U.S. during World War 1. These tea containers were referred to as “tea balls” and were also made from cotton gauze tied with string. Two of the businesses that sold tea balls were the Private-Estate Coffee Co. and the Hirschhorn family (who later formed the National Urn Bag Company). In July of 1919, Benjamin Hirschhorn was granted a patent (U.S. Patent No.: 1,310,796) for a tea ball closed by an aluminum band. This invention facilitated the automated production of tea balls, which permitted the National Urn Bag Company to increase its tea ball production from 12 million hand-made tea balls in 1920 to 235 million machine-made tea balls in 1930.

Tea containers similar to the German “tea bombs” were also manufactured and sold in the U.S. during World War 1. These tea containers were referred to as “tea balls” and were also made from cotton gauze tied with string. Two of the businesses that sold tea balls were the Private-Estate Coffee Co. and the Hirschhorn family (who later formed the National Urn Bag Company). In July of 1919, Benjamin Hirschhorn was granted a patent (U.S. Patent No.: 1,310,796) for a tea ball closed by an aluminum band. This invention facilitated the automated production of tea balls, which permitted the National Urn Bag Company to increase its tea ball production from 12 million hand-made tea balls in 1920 to 235 million machine-made tea balls in 1930.

While the cotton gauze tea balls were popular and produced on a fairly large scale, they were recognized as having deficiencies. Even with automated production, they were still expensive to manufacture. Of more concern, however, was the taste the cotton gauze imparted to the tea. In an attempt to address these deficiencies, businesses started selling pillow-type tea bags formed from sheets of perforated non-woven material, such as cellophane, parchment and thermoplastic fiber. These pillow-type tea bags were typically formed by gluing together two opposing sheets of non-woven material at their edges to form a single chamber, within which the tea was deposited. An example of such a tea bag is disclosed in U.S. Patent No.: 2,149,713 to Webber, which issued in March of 1939. These pillow-type tea bags had their own issues, however. The web material often ruptured and/or did not permit the tea to be readily infused into the water. In addition, the glue used to form the bag imparted its own peculiar taste to the tea.

The foregoing problems with cotton gauze tea balls and pillow-type tea bags were finally solved with the merger of two new developments made on opposite sides of the Atlantic. The first development occurred in the mid 1930s and was made by a U.S. scientist with a degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), while the other was made in war-torn Germany after World War 2 by a man without a university education.

In the early 1930s, Fay H. Osborne, an MIT graduate and paper chemist at the Dexter Corporation played a principal role in developing an automated, continuous process for making porous, long fiber paper, which was ideal for making tea bags. This type of paper had been used by artisans in Japan for a long time and was known as yoshino paper; however, it was made by hand and, thus, was of inconsistent quality and quite expensive. Mr. Osborne’s invention (for which he was granted U.S. Patent Nos.: 2,045,095 and 2,045,096 in 1934) permitted long fiber paper to be manufactured in greater quantity and at a much reduced cost. He utilized the fiber from the abaca plant (musa textilis), which is a species of banana native to the Philippines. Unfortunately, the supply of abaca was interrupted by World War 2, so Dexter Corporations’s long fiber paper did not become significantly commercialized for use in tea bags until after World War 2.

The foregoing problems with cotton gauze tea balls and pillow-type tea bags were finally solved with the merger of two new developments made on opposite sides of the Atlantic. The first development occurred in the mid 1930s and was made by a U.S. scientist with a degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), while the other was made in war-torn Germany after World War 2 by a man without a university education.

In the early 1930s, Fay H. Osborne, an MIT graduate and paper chemist at the Dexter Corporation played a principal role in developing an automated, continuous process for making porous, long fiber paper, which was ideal for making tea bags. This type of paper had been used by artisans in Japan for a long time and was known as yoshino paper; however, it was made by hand and, thus, was of inconsistent quality and quite expensive. Mr. Osborne’s invention (for which he was granted U.S. Patent Nos.: 2,045,095 and 2,045,096 in 1934) permitted long fiber paper to be manufactured in greater quantity and at a much reduced cost. He utilized the fiber from the abaca plant (musa textilis), which is a species of banana native to the Philippines. Unfortunately, the supply of abaca was interrupted by World War 2, so Dexter Corporations’s long fiber paper did not become significantly commercialized for use in tea bags until after World War 2.

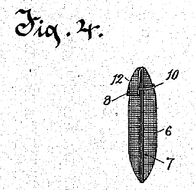

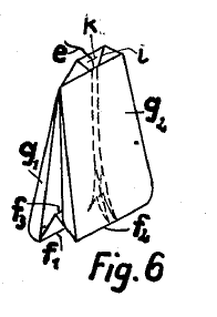

U.S. Patent No. 2,593,608

U.S. Patent No. 2,593,608

The modern tea bag was born when the long fiber paper developed by Fay Osborne was married with the double chamber tea bag invented by Adolf Rambold of Germany. At the end of World War 1, Mr. Rambold went to work, as a teenager, for Teekanne GmbH, the maker of the “tea bombs”. At the time, Teekanne was working on a machine for automating the manufacture of tea bombs, but couldn’t get it to work. Mr. Rambold solved the problem, thus beginning a life-long career in tea package innovation. Although he did not have a university degree, Mr. Rambold was a prolific inventor, who made numerous contributions to the development of the modern tea bag. He invented the combination tea bag and paper wrapper in 1935 (U.S. Patent No.: 2,101,225), as well as several different machines for manufacturing tea bags. However, his most important invention was the double chamber tea bag, for which he received U.S. Patent No. 2,593,608 in 1952 (based on a 1948 application). The double chamber tea bag was made from a single piece of paper with no glue or heat sealing. It was easy to manufacture and made a better cup of tea because it had two chambers and four sides, which permitted water to optimally circulate around the tea. Moreover, it was ideally suited to utilize the new long fiber paper developed by Fay Osborne.

Although the Thomas J. Lipton Company is often incorrectly credited with inventing the double chamber tea bag, Lipton adopted it early on, introducing it in 1952 and selling it under the trademark “FLO THRU” beginning in 1954. Lipton’s use of the double chamber tea bag helped make it the most popular type of tea bag in the world, up to this day. As a testament to the quality of its design, the double chamber tea bag has essentially the same construction today as it did when Mr. Rambold invented it in 1948. However, Mr. Rambold kept improving the machinery for manufacturing it. Indeed, the last patent application Mr. Rambold filed (at the age of 87) was for an improved machine for manufacturing double chamber tea bags.

Although the Thomas J. Lipton Company is often incorrectly credited with inventing the double chamber tea bag, Lipton adopted it early on, introducing it in 1952 and selling it under the trademark “FLO THRU” beginning in 1954. Lipton’s use of the double chamber tea bag helped make it the most popular type of tea bag in the world, up to this day. As a testament to the quality of its design, the double chamber tea bag has essentially the same construction today as it did when Mr. Rambold invented it in 1948. However, Mr. Rambold kept improving the machinery for manufacturing it. Indeed, the last patent application Mr. Rambold filed (at the age of 87) was for an improved machine for manufacturing double chamber tea bags.

Proudly powered by Weebly